Tucked away in the Hollywood hills, an elite group of scientists from across the country and from a grab bag of disciplines -- rocket science, nanotechnology, genetics, even veterinary medicine -- has gathered this week to plot a solution to what officials call one of the US' most vexing long-term national security problems.

Their work is being financed by the Air Force and the Army, but the Manhattan Project it ain't: The 15 scientists are being taught how to write and sell screenplays.

At a cost of roughly US$25,000 in Pentagon research grants, the American Film Institute is cramming this eclectic group of midcareer researchers, engineers, chemists and physicists full of pointers on how to find their way in a world that can be a lot lonelier than the loneliest laboratory: the wilderness of story arcs, plot points, pitching and the special circle of hell better known as development.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

And no primer on Hollywood would be complete without at least three hours on "Agents and Managers."

Exactly how the national defense could be bolstered by setting a few more people loose in Los Angeles with screenplays to peddle may be a bit of a brainteaser. But officials at the Air Force Office of Scientific Research spell out a straightforward syllogism:

Fewer and fewer students are pursuing science and engineering. While immigrants are taking up the slack in many areas, defense laboratories and industries generally require American citizenship or permanent residency. So a crisis is looming, unless careers in science and engineering suddenly become hugely popular, said Robert Barker, an Air Force program manager who approved the grant. And what better way to get a lot of young people interested in science than by producing movies and television shows that depict scientists in flattering ways?

Teaching screenwriting to scientists was the brainstorm of Martin Gundersen, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of Southern California and sometime Hollywood technical adviser, whose biggest brush with stardom was bringing a little verisimilitude to Val Kilmer's lasers in the 1985 comedy Real Genius.

More recently, he was asked to review screenplays by the Sloan Foundation, which awards prizes for scientific accuracy, and found most to be "pretty dismal," as he put it.

"My thought was, since scientists have to write so much, for technical journals and papers, why not consider them as a creative source?" Gundersen said.

He already had contacts at the American Film Institute, and he quickly persuaded Barker, who oversees several of his other grants, to endorse what began as a weekend seminar last summer and was expanded to five days this year. The Air Force is providing US$100,000 annually for three years; the Army Research Office has added US$50,000 this year.

Much of that money will pay for other like-minded efforts: Gundersen is also starting a workshop for high school students at the film institute, and he plans to get entertainment industry people to lead seminars at scientific conferences and to give seminars to up-and-coming screenwriters on how to reach out to scientists for help with accuracy.

For now, though, the hopes of the Pentagon for a science-friendly cinema seem to be riding on the shoulders of people like Bogdan Marcu, an engineer for Boeing's rocket propulsion division who is nursing an idea for a spy thriller, and Sam Mandegaran, a PhD candidate in electrical engineering at the California Institute of Technology who says he wants to become a director of science-friendly movies for young people because "adults are a lost cause."

Around a table at the institute's campus, they and their colleagues, chosen from some 50 applicants, listened this week as Syd Field, author of some of the most popular how-to books on screenwriting, steeped them in the ABCs of three-act structure.

They wrestled with how to reconcile the cinematic suspension of disbelief with the scientific method and with their basic purpose of bringing accuracy to the screen.

And they got feedback for their own script ideas. A disaster movie set at the Olympics, where athletes get a virus that makes them smarter? (Problem: The main character was the virus.) A biopic on the inventor of the Ferris wheel, who died a sad and lonely alcoholic? ("Do I have to like the character?" asked its author, Jeffrey Hoch. Hardly -- think Raging Bull, he was told by Alex Singer, a veteran television director.)

Hoch was full of searching questions. "When I'm writing for a scientist, I write for my peers," he said. "Who are we writing for? The viewer? The director? The money people?"

"Tell your story for you," Field urged him. "Then, go back and rewrite it."

Gundersen chimed in, "It's different from writing for a science journal. That has to be right; you'd better not make a mistake, because people will beat the hell out of you. In a movie, I wouldn't want to say it doesn't have to be right, but it's different."

Singer added, "They will not forgive you for being bored. They'll forgive you for anything else."

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

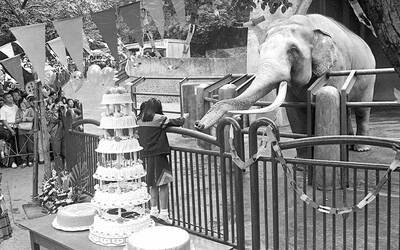

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

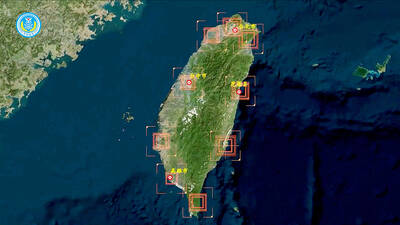

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger