When His Holiness the Dalai Lama gives public teachings in India, attendees would be well advised to bring a cushion, an FM radio, a cup and a sunhat and given the security checks that take place, as little else as possible.

But one need not travel all the way to India, like a group of 500 Taiwanese men and women are doing in July, to meet up with one of the world's most recognized spiritual leaders.

The 14th Dalai Lama, leader of the Tibetan Buddhist faith, has a travel itinerary that would put any jet-setting corporate executive to shame.

He turns 70 on Wednesday, July 6, and he has spent the last 46 years in exile based in India, but traveling far and wide with his messages of peace, compassion and love. The demand for justice for the Tibetan people that started with freedom has now been toned down to greater autonomy under Chinese jurisdiction.

Tibet may well have been forgotten, were it not for this remarkable man.

Born to a humble farming family in 1935 in a tiny Tibetan village, the life of Lhamo Dhondrup, as he was known then, took an extraordinary turn when he turned 2 years old.

A group of Buddhist monks recognized him as the 14th incarnation of the Dalai Lama, traditionally the spiritual and political leader of Tibet. At the age of 6, he was in a monastery being educated in the tenets of Buddhism.

He lived in his beloved Tibet for only 24 years. The larger part of his life has been spent in Dharamshala which translates as "abode of religion," a small northern Indian hill town, from where he runs his Tibetan government-in-exile.

China invaded Tibet in 1949, and when the Tibetan government broke down in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India disguised as a soldier while Chinese troops cracked down on a Tibetan uprising against the occupation of their homeland.

More than 80,000 Tibetan refugees followed the Dalai Lama. But in the years that followed his departure, about 1 million Tibetans died in prisons and labor camps in Tibet, according to the Tibetan government in exile.

Human rights organizations say Tibet's unique culture and its people have been systematically persecuted by China, which established a Tibet Autonomous Region 40 years ago.

In the early years of his exile, the Dalai Lama took the cause of the Tibetan people to the United Nations. The UN General Assembly called on China to respect the human rights of Tibetans and their desire for self determination.

The Dalai Lama over the years has toned down the demand for a free Tibet. In a statement issued earlier this year on the occasion of the 46th anniversary of the Tibetan uprising against Chinese occupation, he said he was committed to not seeking independence for Tibet from China.

"I am convinced in the long run such an approach is of benefit to the Tibetan people for material progress," he said. But he also laments the lack of "true ethnic harmony based on trust" in Tibet.

"The absence of genuine stability in Tibet clearly shows that things are not well."

The Dalai Lama has renewed contacts with the Chinese leadership and says the interactions have been improving. His attempts at peaceful negotiations with China for autonomy for Tibet won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989.

Until the long-standing dispute is resolved to the mutual benefit of China and the Tibetan people, the Dalai Lama will continue to travel far and wide to garner support for the Tibetan cause.

He has visited 55 countries -- some of them several times. He has just returned from a visit to Sweden and Norway. Soon after his 70th birthday on Wednesday, he will travel to Switzerland and then onto the United States where he will criss-cross the country for about two months.

India is home not only to the Dalai Lama, but also to about 100,000 Tibetan refugees who live in 35 settlements and numerous smaller communities striving to keep their cultural identity alive while adapting to a foreign land.

Many of them may still dream of a free Tibet in variance with the Dalai Lama's current vision, but they all agree that it is their leader's charismatic personality that has kept the issue of Tibet alive in the international arena.

A columnist for Time magazine wrote, in response to a rhetorical question on what made the simple Buddhist monk heading an unrecognized government-in-exile of an unrecognized nation of 6 million Tibetans so interesting: "Perhaps because he is also a diplomat, a Nobel laureate, an apostle of nonviolence, an advocate of universal responsibility and a living icon of what he calls `our common religion of kindness.'"

As their leader turns 70, Tibetans may pause to think, what comes after? In a recent interview with the Hindustan Times newspaper, the Dalai Lama said, "If we cease to be a refugee community and can live in democratic Tibet, then I don't think there should be a successor to me after I die."

But, he added, "If I was to die in the next few months or before we are able to return to Tibet, there will be a new Dalai Lama."

He does not know yet where the next leader will be found. But when the time comes for him to die, he will know, he said.

Until then, the smiling monk will continue to inspire through his teachings and will not let the world forget the plight of the Tibetans.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

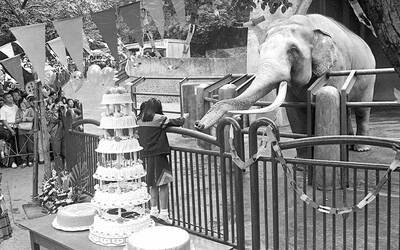

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

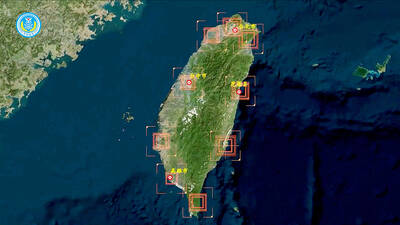

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger