One of Taipei's greatest advantages is that when the need to get away from it all becomes overwhelming, then hopping on the right city bus will usually do the trick to leave the hustle and bustle behind and soak in a bit of nature. That was my objective on a recent weekend: to escape the city using only city buses, and Muzha, I discovered, is the ideal place to do just that.

At the southern edge of Taipei City, Muzha can feel at times light years away from the cosmopolitan glass-and-steel vertical jungle of downtown, though they are, in fact, only a few kilometers apart. The district, with its narrow roads, elderly population and the predominance of Taiwanese over Mandarin being spoken, feels almost like a southern rural village roped into the city. New modern high-rise apartments springing up suggest Muzha may yet be fully co-opted into the city, but for now, its mostly squat, humble apartment blocks provide some human scale to neighborhoods and views of the nearby hills that form the southern rim of Taipei's basin. And from almost every point in Muzha one can see the imposing Chi-nan Temple (指南宮) perched atop the mountain for which the temple is named.

Aside from being a major worship location for Daoism in Taiwan, Chi-nan Temple is also the nexus of a network of hiking and biking trails that spreads out over the hills from Nangang on the eastern edge of Taipei all the way southwest to Sindian. Starting in Gongguan, the 530 bus runs directly to the temple, from where a coin toss can decide whether to head in the direction of Shenkeng to the northwest, or through the tea farms of Maokong and eventually over the hills and into Sindian. My coin told me Sindian.

Magical Maokong

From Chi-nan Temple, a quick stroll along the road out the back of the complex leads to Maokong, formerly one of the main tea-producing centers of northern Taiwan that was allegedly named for the holes worn into the valley's streambed that locals said looked as though they had been dug by a cat. Things have changed considerably since the area's tea-producing heyday in the late 19th century, as most of the farmers on the mountain have long since given themselves over to the lucrative restaurant and teahouse businesses that attract car-driving throngs on weekends.

For this reason, hiking through Maokong is best enjoyed well before noon on weekends to avoid fleets of aggressive drivers on the winding, narrow mountain roads. Most of the hiking, however, can be done off paved roads and on established trails trod down by intrepid contingents of mountain bikers and teams of senior citizens who can be seen hiking in orderly rows zigzagging up and down the hills in the morning hours.

From Chi-nan Temple, following the Dacheng Dian trail and then linking up with the Taipei Tea Promotion Center Trail, the leisurely hiker can reach this small but interesting exhibition center in about an hour. The center features displays of Taiwan's various strains of teas, tools and machinery used in tea production and an informative multi-lingual audio-visual introduction to the history of tea production in the area. Guides from the Liu-kung Agricultural Foundation are on hand, as well, to offer introductions in Chinese and English to the center's displays and to the history of tea production in Wenshan. Open on weekends, comfortably air-conditioned and always ready to offer free cups of locally produced Tieh Kuan-yin Tea, this is understandably a popular resting spot for hikers passing through Maokong. Other options for a respite or food, or both in my case, include any of the scores of teahouses that line the road that snakes its way up the mountainside.

Cave exploring

Plenty of tea is still produced in Maokong by holdout farmers and the remainder of the hike to Sindian passes through the more picturesque of their fields, at its higher elevations, with arresting views of Taipei and, of course, Taipei 101 providing some postcard juxtapositions.

So after enjoying far too much of the tea-leaf fried rice, tea-leaf fried veggies and tea jelly and drinking too much Tieh Kuan-yin tea in Maokong, it was high time on my visit to burn off some calories by hitting the small trail that leads over the hill through an isolated glen of vegetable and tea fields to one of the best-hidden temples in Taipei. Tucked partially behind a waterfall, Yinhe Cave Temple is a tiny Buddhist structure carved mid-way up a 50m cliff that enjoys a spot in local lore for being a weapons depot for resistance fighters against the Japanese occupation at the beginning of the last century. In fact, many of the hiking trails that still exist in the area were once used by Shenkeng-based guerillas fighting the Japanese and some of the nearby peaks were used to send signals about Japanese troop movements.

I had been told that after heavy rains, Yinhe Temple becomes concealed by falling water, but scarce rain this season has left most of the temple exposed. That was a bit of a let-down because the temple itself is a rather bland concrete slab. But the reduced waterfall, nonetheless, is quite spectacular, dumping over its precipice in a jungle setting ringed by blazing pink and white azaleas that are now in bloom. A flat, concrete viewing area next to the base of the falls is a perfect picnic setting in dry conditions.

Having trekked from Chih-nan Temple, down and up one valley to Maokong and over one ridge to the waterfall, I had begun to feel that such an outing held its share of adventure. But my bubble was burst when a chipper family with hip-high toddlers in tow came into view on the last stretch of road that leads out to National Route 9 running from Ilan to Sindian. The colors of the forest, the hush of swaying bamboo groves, the sight of old men tilling fields had all led me to believe I had traveled great distances and left most of what was familiar behind. But no, it's just a family hiking trail only one quick corner out of sight from the city. I turned that corner by walking a final kilometer along Route 9 into Sindian and catching the 650 bus back to Gongguan feeling refreshed all the same.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

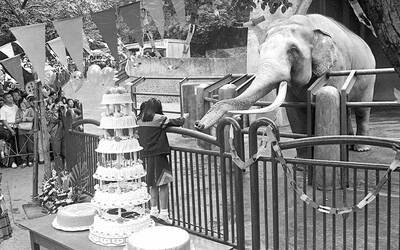

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

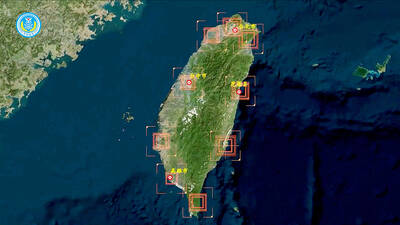

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger