The aptly named exhibition The Garden of Light features the sparkling light and luminescent color that emanates from the holographic art, paintings, prints, mobiles and installations of German artist Dieter Jung.

On view at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum until May 8, with a smaller complementary display of prints at the German Cultural Center, the exhibition will then travel to the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

In the Taipei Fine Arts Museum's lobby, the Calder-like mobile of silvery convex mirrors titled Transoptics slowly moves reflecting images of passersby upside-down. It is a good introductory piece to prepare the viewer for the show where the the work on view is about optical effects, visual perception, and how light hits on reflected surfaces.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE TAIPEI FINE ARTS MUSEUM

Jung's exhibition in Taiwan starts with the story of the Chinese magic mirror. Created over 2,000 years ago in China, a shiny bronze disk was made so that an image of the relief on its underside could be projected onto a screen by shining a light on it. The technology behind it predates holography as the same principle of manipulating light-waves.

The obsoleteness of the mirror serves as a lesson that advanced technology will not go beyond novelty without a good concept behind it. So, it is that combination of scientific technology and aesthetic conception that motivates the artist, who also displays his own magic mirror.

Trained in theology before becoming an artist, Jung's background in philosophical investigations of existence and belief clearly informs his art. Though the works are secular, many of the non-narrative pieces would fit into any temple or house of worship as the works have an ethereal quality.

Perhaps the absence of both a narrative and a figure allows the viewer to read any kind of meaning into a simple geometric shape.

When Jung's works were shown at the Hara Museum in Tokyo, visitors sat down in front of them to meditate, as the works do have that unearthly aura about them.

So Jung was quite pleased when one of the Taipei museum guards said that in the holograms he could see eternity.

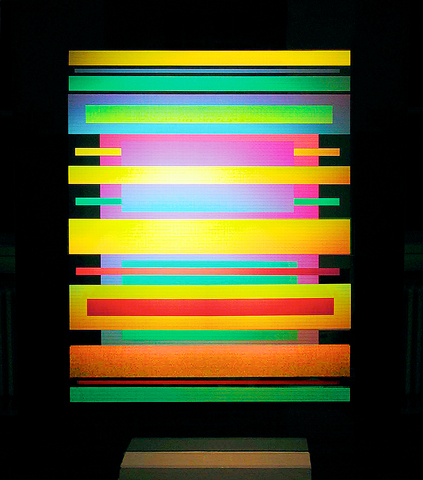

Perhaps the guard was referring to the Parochial RGB series of brightly hued geometric shapes on flat rectangular pieces of mirrored glass installed on plinths. From a distance, the holograms burst with intense, glowing color.

In holography, three-dimensional images are created on a flat surface through the diffraction of light waves with a laser. Many popular holographs contain representational images such as people, animals and buildings. In Jung's work, however, he shows that profound thoughts can be stated abstractly with only a simple line or shape.

The human figure is mainly absent from the work, with the exception of Self Portrait with Prism, where the artist is portrayed in the realm of his special technique. And a series of large white-on-white acrylic paintings bear the portraits of famous men such as Sigmund Freud and Ezra Pound. Since the contrast of the colors is slight, the images can only be seen from a distance.

It is the constant negotiating of the space around the work that the viewer must confront. So, whether the works are paintings with low-value contrast or the iridescent holographic panels, the viewer becomes a dance partner to the work, taking a step forward and back, tilting the head sideways until the right combination of distance and light are achieved to see the work in all its shimmering luminosity.

The third floor of the museum has always been a problematic space to exhibit, as the area encircles the bank of escalators and feels more like a foyer than an intimate viewing area. So a small alcove was created for the work Lines of Flight.

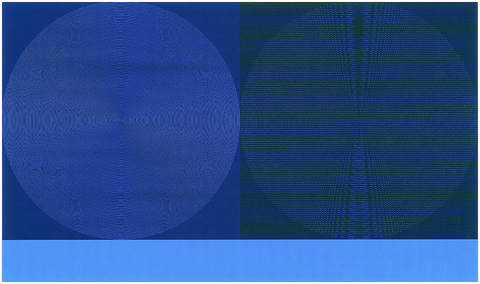

A large window was cut into the wall that contains a moving floor-to-ceiling holograph of vertical lines in primary colors that give the appearance of monolithic skyscrapers.

Jung exhibits a more literary and figurative type of work at the German Cultural Center in LightColourSpace.

A popular series of posters he made for a publisher of philosophy books in the 1970s includes portraits of thinkers such as Goethe, Kant, Einstein and Schiller superimposed with an intricate netting of woven lines.

And the pivotal piece on display is a small holograph of Goethe -- who developed his own color theory -- wryly perched on a stack of the famous writer's books.

This smaller exhibition about appearance and disappearance also provides a good opportunity to learn more about the center's facilities and to contemplate the juncture between art and science.

Event Information:

What: The Garden of Light

Where: The Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 181 Zhongshan N Rd, Sec 3, Taipei (

When: Until May 8, Tuesday to Sunday, 9:30am to 5:30pm

Tel: (02) 2595 7656

Information: http://www.tfam.gov.tw

What: LightColourSpace

Where: The German Cultural Center, 12F, 20 Heping W Rd, Sec 1 (

When: Until April 15, Monday to Friday, 10am to 8pm

Tel: 2365-7294

Information: http://www.dk-taipei.org.tw

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the