Contemporary English-language poetry can be hard going, but by and large it's a lot more accessible than it was 25 years ago. Poets such as Australia's Les Murray and Ireland's Seamus Heaney have staged a reaction against the willful obscurities of modernism, and today there is once again a wide range of verse on offer. Whereas in 1980 you could be pretty certain of being bamboozled, terror-stricken or at the very least honestly perplexed by anything set out other than in straight prose, today there's much more variety, and you can never be quite sure what to expect.

Madeleine Marie Slavick was the most impressive verse contributor to the new Taiwan magazine Pressed (reviewed in Taipei Times Sept. 24, 2004), and here she is with a new collection, elegantly titled Delicate Access, with translations into Chinese (by Luo Hui) printed alongside the poems.

Everything about this book spells poise and a terse intelligence. There is nothing unbuttoned, no flavor of Walt Whitman or Allen Ginsberg, no roar of endangered tigers from the depths of the jungle, no rousing protests against oppression (though there is "Which China prison were your clothes made in?"). Instead, we find delicacy (as in the title), suggestions of intimacies (past and future) and a minimalist concentration. If these poems were paintings, they would be old-style Chinese sketches -- a twig here, a cloud there, and the view of a distant cottage high on what the artist hints could be a mountain.

Or, to make an ornithological comparison, the Madeleine Marie Slavick imagined from these verses would not be an eagle, but not a sparrow either. She would, perhaps, be a sleek and assured heron, picking its way across some Guangdong mud flats. But of course, when the moment comes, herons strike with lightening speed and accuracy.

The imagined location is Guangdong because Slavick, though raised in Maine, has lived in Hong Kong since 1988. Not surprisingly, the city features prominently in these poems. The book is divided into chapters, and one is called "Permanent Resident" -- as the author explains "the odd, bold classification on my mandatory Hong Kong Identity Card." The verses it contains evoke a city that's at times surprisingly poetic, though a feeling approaching anger can take the poet over. A Sunday junk trip is viewed at best sardonically, and on a Hong Kong sidewalk she ponders "Will this mobile phone ever be the heart?"

One excellent poem about the Star Ferry, which links Hong Kong Island with Kowloon, makes comparisons with Jesus -- walking on water, the Catholic stations of the cross, and the resurrection. The boat passes office towers "receiving the sun's orange champagne," and when she wonders whether their corporations own the very water, or will perhaps copyright their buildings' reflections in it, you remember William Blake's "chartered (i.e. bought-up) Thames."

These poems repay close attention, but they're not "difficult" as such. Because they tend towards concision, however, you can look at one for some time before realizing what lies behind it. But that meaning isn't concealed so much as efficiently built-in. There are no wasted words in Madeleine Slavick's well-crafted verses.

One memorable section is called "Colour." Red calls up images of traffic lights, war, advertising and menstruation, while blue evokes those of sea, sky, eyes and "the coldest wavelength." There's a wonderful short poem on pink and purple. Knowing how easily these colors become attached to "prissy pastel pantsuit(s)," she calls on them to instead "drink long opinions full of violets, generate lush heat, be sure of your admirers." (The commas are added, with apologies, for clarification in the context of a prose review -- in the notes Slavick thanks Adrienne Rich for teaching her to use, instead of commas, empty spaces).

After a set of crowded, tumultuous prose poems, the book ends with a single lyric called "Envoi." It goes as follows (this time the comma is Slavick's): "He shakes the ice in the summer glass, clarity against clarity." Ice and glass, both transparent (hence "clarity"). But why "summer?" Because it conveys light, brightness, happiness. And that one word makes the poem.

This book isn't entirely made up of words. Slavick is also a photographer and there are seven color photos included. But the visual connections are more than this. She thanks the Australian artist Stephen Eastaugh for a phrase (Eastaugh was an artist in residence at Taipei's Artists Village earlier this year, fresh from Antarctica) and her poems have appeared in installations. Where her poems record emotions, they are frequently ones prompted by things seen. This is especially apparent in the section "To Nature," made up of minute poems, shorter than haiku, that are the least successful things in the collection. They may feel better in their Chinese versions, but in English they seem like notebook fragments looking for a home in a structured poem. On the other hand, Slavick may reply that lack of structure is their whole point.

Madeleine Marie Slavick may well be the best English-language poet Hong Kong has ever been home to. The English poet Edmund Blunden (1896-1974) lived there for a time, but these poems are often better than his. This is a most impressive collection.

An exhibition of Madeleine Marie Slavick's photographic work will be held at Taipei's Wisteria/ Zitenglu teahouse (No. 1, Lane 16, Xinsheng South Road) from 12 March to 12 April 2005. Delicate Access is already available there and can also be obtained direct from the publishers at www.sixthfingerpress.com.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

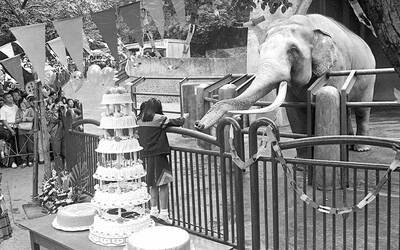

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they