If you ask Huang Chung-mou (黃忠謀) what his profession is, he will tell you that he is in the cleaning business, sort of, a cleaning job that people usually stay away from. Bone-washing or bone-cleaning is an ancient practice which dates back to the Qin dynasty (秦朝) 2,200 years ago. In Taiwan today, where cremations are widespread, some people still exhume an ancestor's bones, cleaning them and reburying them. Huang is one of the few in the business.

"It is a sign of the greatest respect to the ancestors," said Huang about the purpose of bone-cleaning. "I see my profession as a profession of virtue and also a way to accumulate benevolent actions for my next life and for my descendants," he added.

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHIH FU-YING

Bone-washing is usually a family business, handed down from generation to generation. In the Huang family, there were three generations who conducted the business in China. Since migrating to Taiwan, four generations of the family have continued the profession. Huang Chung-mou, aged 60, is the sixth generation and his two sons Huang Yung-ping (黃詠斌) and Huang Ya-chung (黃雅鐘) are the seventh generation.

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHIH FU-YING

Women in the family, however, are not taught the skills of bone-washing. Huang said it is believed that it would blaspheme the dead if the bone-washer did the work when she was menstruating.

"Because you are dealing with dead bodies, there are rules and taboos that we have to follow," Huang said, stressing that his family is the only family in Taiwan strictly following the ancient rules.

The first step of bone-cleaning practice is to have the feng-shui master to pick a good day for the ceremony, based upon the birth dates and eight characters of the deceased. The family of the deceased need to prepare fruits, cookies (or a kind of dry food), flowers, incense and paper money for the dead, before the exhumation begins.

The hardest part of the job is when opening the coffin, Huang said. A strong smell assails the workers and families standing by the tomb. "It is hard, but you get used to it," he said.

According to the rituals, the daughters or granddaughters of the deceased have to hold open a black-colored umbrella when the coffin is opened.

"The use of the black umbrella is to hold together the spirit of the dead, preventing it from falling apart," Huang said. Another meaning of this ritual, according to Huang, is that the daughters-in-law of the family pay respect to the ancestors.

After collecting the bones from the coffin, Huang wraps the bones in a yellow-colored cloth and takes them back to his work studio for the cleaning procedure.

Normally, it takes 10 to 12 years for a body to completely disintegrate, depending on the texture of the soil and the size of the coffin. Often, Huang finds damp bodies after exhumation. "In the case of damp bodies, I spray two dozen bottles of rice wine onto the body and then pad the coffin a bit to provide better ventilation. This is to let the body decay naturally. Then we rebury the coffin and wait for another two years for another exhumation," Huang said.

Unlike other bone-cleaners, the Huang family said they never use chemicals or any unnatural method to separate the body and the bones.

"This is because it would be a violation of the rules of the nature," Huang said.

If we separate the body with unnatural forces, it would be as if the deceased was facing a second- death experience. It is very immoral," Huang said.

As for other bone-washers, they usually charge more than NT$10,000 for using chemicals to dissolve the body.

"But we would rather not earn that money because it's just unnatural," Huang said.

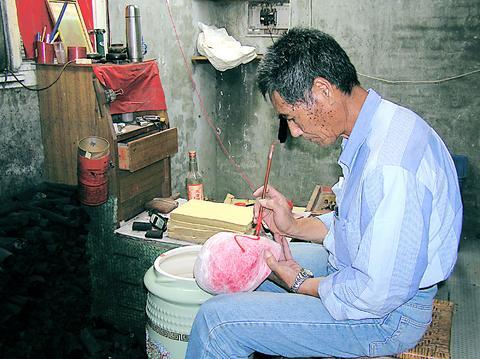

There are also traditional rules about cleaning the bones. Huang uses brushes to clean the residuals on the bones, piece by piece. And then he recombines the bones like a jigsaw puzzle.

On each edge of the bones he paints them with red ink "which represent the veins of the body." And then each piece of the bone is wrapped with paper made of bamboo, and then placed back in a porcelain jar.

"Remember, the bones need to be placed in a sitting-down position in the jar, the same position humans are in the womb," Huang added.

"In a way, what we are doing is to find a nice comfortable new home for the deceased," Huang said.

Having cleaned the bones of more than 10,000 bodies, has Huang ever confronted anything supernatural? "There was one occasion when the deceased came to our house, requesting that we changed his jar for a higher-priced jar. We at first did not believe it, until the deceased told his family the same request," Huang said.

"There was another time we helped clean the tomb of an unknown child, for a graveyard. The night before we reburied the child, I dreamt of a child telling me what his name was and asking me to engrave it on the tomb," said Lin Li-hua (林麗華), Huang Chung-mou's wife.

After 46 years of experience, Huang can tell stories from the bones. The bones of those who suffer from chronic diseases tend to decay slower because the long-term use of medication acts as a preserving chemical, he said. "And those having drinking problems tend to have darker colored bones, and they usually show symptoms of osteoporosis."

For the past 46 years at his bone-cleaning practice, the price for his service has been set at NT$2,500, even though the average price has risen up to NT$20,000. It is another sign of Huang's sticking to the traditions.

As cremation becomes a more common funeral practice than burial, has Huang ever been worried that the bone-cleaning business might be nearing its end?

"It might gradually diminish. But I never worry too much for the future. As long as I have one day of business, I will do a good job and maintain a quality service," he said. "Besides, we are still dealing with bodies that passed away 10 to 12 years ago. Even if the business is going down, it would still take another 10 to 12 years, I guess."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the