Western society has denounced racism, sexism and anti-Semitism, mobilized against ageism and genderism, anguished over postcolonialism and nihilism, taken arms against Marxism, totalitarianism and absolutism, and trashed, at various conferences and cocktail parties, liberalism and conservatism.

Is it possible there is yet another ism to mobilize against?

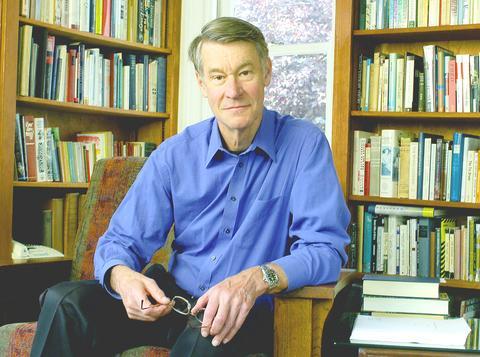

Robert Fuller, a boyishly earnest 67-year-old who has spent most of his life in academia, thinks so, and he calls it "rankism;" the bullying behavior of people who think they are superior. The manifesto? Nobodies of the world unite! -- against mean bosses, disdainful doctors, power-hungry politicians, belittling soccer coaches and arrogant professors.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

"I wanted a nasty word for the crime, an unpleasant word, a stinky word," he said, referring to his choice of the word rankism. "Language is incredibly important in making political change. I always go back to that word sexism and how it became the catalyst for a movement."

Fuller wants nothing less than moral as well as behavioral accountability from the people in charge, whether of governments, companies, patients, employees or students. And he pitches his quixotic notion in a book, a Web site (breakingranks .net), in radio interviews and in lectures at universities and business gatherings that could be considered breeding farms for somebodies.

"The theory has the potential to explain many things we just ignore as a given," said Camilo Azcarate, Princeton University's ombudsman, who recently attended one of Fuller's lectures and bought several copies of his book to give to friends. "Democracy and education should concentrate on creating virtuous citizens. This is exactly the kind of discussion we need to have."

not a movement yet

Fuller began postulating these theories on the Internet several years ago, and then brought them together last year in a book called Somebodies and Nobodies (New Society Publishers), published recently in paperback. He can't answer how, exactly, his lofty ideas might translate into political or legal action. "I don't see the form the movement will take," he confessed in an interview at his home in Berkeley. "But I don't feel too bad about it because Betty Friedan told me she didn't have any idea there would be a women's movement when she wrote The Feminine Mystique. You need five years of consciousness-raising before you find the handle."

Friedan provided a blurb for his book. Other supporting blurbers include Bill Moyers, the political scientist Frances Fukuyama and the author Studs Terkel. So far the book has sold 33,000 copies (including bulk sales); and his Web site totals 2,000 to 3,000 visitors a week, his Web master, Melanie Hart, said.

Fuller's appeal nonetheless eludes some critics. In one of the few reviews of Somebodies and Nobodies, Clay Evans, books editor of The Daily Camera newspaper in Boulder, Colorado, was dismissive. Fuller's concepts, he wrote, "were old when Jesus was making fishers of men."

But with others, he has struck a chord. Among the 2,000 people who had downloaded a working manuscript of his were Mary Lou and Ann Richardson, two sisters living in Roanoke, Virginia. They were so inspired by that early version that they eventually met with Fuller after the book was published. The women, Ann Richardson said, had been taking care of an aging mother with Parkinson's disease and were distressed by how people's treatment of her changed after she lost her ability to speak.

The sisters began their own Dignitarian Foundation, described on its Web site (dignitarians.org) as "an organization dedicated to promoting and protecting the intrinsic right to human dignity."

fast track to academia

This was not the role Fuller seemed destined to fulfill. Designated a math and science whiz kid, he entered Oberlin College at age 15, expecting to follow the path of his father, Calvin Fuller, a physicist at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey who was co-inventor of the solar cell. After Oberlin, Fuller accumulated credentials with breathtaking speed. By 18 he was enrolled in graduate school at Princeton. At 33 he was named president of Oberlin.

In between he learned about politics at the Ecole Normale Supeieure in Paris and economics at the University of Chicago, helped write a significant physics text -- Mathematics of Classical and Quantum Physics -- taught at Columbia University, did a fellowship at Wesleyan University and was dean of faculty at Trinity College in Hartford.

His peripatetic intellectual ambitions coincided with an era of social upheaval. Fuller left for Oberlin as an undergraduate in 1952, thinking Dwight Eisenhower was the perfect next president. By the time he returned to Oberlin as its president in 1970, he was ready to lead the college through the revolutions of the period -- making changes in admissions policies for African-American students, abolishing course requirements, ending parietal hours.

Then, after 22 years on the academic fast track, he quit -- at age 37. He left Oberlin and his first wife, with whom he had had two children, and traveled around the world for three months. Then he settled in Berkeley where, he said, "I sat still for two years, read 200 books and completely re-educated myself." Among other things, he began to realize his role model may have been his mother, Willmine Works Fuller. "She wasn't very concerned about social justice, but if someone tried to step on her toes, watch out," Fuller said, recalling a protest his mother organized against putting an airport near his hometown of Chatham, New Jersey.

academic turns activist

He became obsessed with the nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviet Union. "The bomb makes nobodies of all of us, that's how I put it now," he said. With a new wife, and eventually two more children in tow (a third wife would come still later) he began traveling through the Soviet Union, paying for the expeditions by giving speeches and raising money from philanthropists. Calling himself a citizen diplomat, he helped arrange televised discussions between Soviet and American scientists via satellite links.

In 1987, Fuller found a crucial advocate for his expensive self-discovery -- Robert Cabot, a novelist and diplomat, but also heir to a family fortune. They traveled together to the Soviet Union, Afghanistan and China and together wrote a few articles. Cabot put money into some of Fuller's citizen-diplomacy projects, which always struggled for financing.

One day Cabot decided to become Fuller's patron. For 15 years he paid him to think -- and to travel, expenses paid. No rankism there: Cabot included pension payments, which kicked in two years ago when Fuller turned 65.

How does Cabot feel about the way his money has been spent? "I am immensely gratified," he said. "I think we are witnessing an extreme abuse of rankism in Washington, right now. Our policy in the Middle East is rankism."

rankism's many guises

Fuller acknowledges that rankism is harder to pin down than other more apparent forms of discrimination -- sex, race and disability. "We try to sniff how much power each of us has by asking: `What do you do? Where did you go to school? Who's your husband?'" said Fuller.

"It's like trying to find out if someone's gay or not, if they're a threat to us or if we can get away with abusing or exploiting them."

Fuller isn't calling for an end to hierarchy, but neither is he simply asking for mere politeness. Controversially, he would get rid of faculty tenure at universities, which he calls "an outdated sacrosanct privilege of a few somebodies held at the expense of many nobodies."

Fuller doesn't rouse his audiences with smooth patter and startling revelations of abuse he's suffered. But his reflective, old-fashioned professorial approach to his sometimes glib, populist theories has been taken in some quarters as a refreshing whiff of sincerity in a skeptical age.

When he spoke at Mount Holyoke College last September, Andrea Ayvazian, dean of religious life, was surprised to see how mixed the audience was: students, faculty members, administrators, staff members and campus workers. "Bob's analysis freed people who considered themselves low in the hierarchy to tell their stories," said Ayvazian, who was a student of Fuller's 30 years earlier. "I saw this had struck a chord in unpredictable circles."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the