Matthew Diffee, a 34-year-old cartoonist from Brooklyn, distinctly remembers when he came to believe he had a shot at becoming a real New Yorker cartoonist. It was around 11:30am on a Tuesday at the offices of The New Yorker, the appointed time at which, for the better part of 50 years, cartoonists have shown up for the ritual submission of their rough drawings to the magazine's cartoon editor -- these days, Robert Mankoff. Diffee crossed paths with an older cartoonist emerging from Mankoff's office, looking as though he'd seen a ghost. Mankoff, the cartoonist confessed, had given him an ultimatum: no more fedoras in his cartoons.

"The look on his face was as though it hadn't occurred to him not to draw people with hats," Diffee said. "I don't own a hat. I've never drawn a hat, and if I ever had to draw a fedora I'd have to Google it. So I thought, `Maybe I'll be OK.'"

Diffee is among the more prolific of the magazine's new generation of cartoonists, a dozen or so men and women mostly in their 30s. Mankoff and David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, are relying upon this group to keep alive the anachronistic but somehow indefatigable cultural institution of the classic single-panel New Yorker cartoon -- known in the humor trade as the gag cartoon.

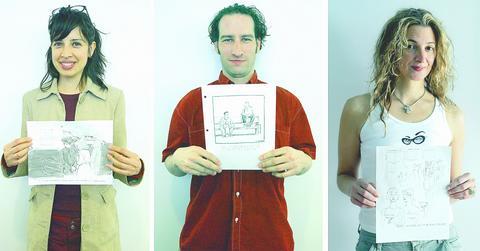

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Many of the magazine's established cartoonists, like Sam Gross, J.B. Handelsman and Robert Weber, are in their 70s and 80s. While the magazine has updated its roster regularly over the years -- Mankoff, a relatively young 59, for example, was hired as a cartoonist in 1977 -- grooming new talent has taken on a new urgency because many aspiring humorists would prefer to work for hipper, more lucrative outlets, like television.

"Everybody understands that if this field is not to die, new people have to be brought in," Mankoff said. "There's no getting around it. It needs new blood."

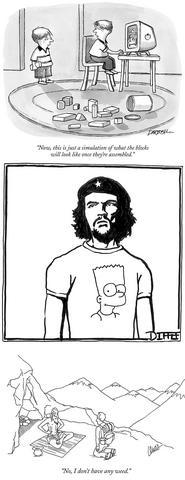

Besides Diffee, who has published more than 50 cartoons in the magazine and whose drawings are distinctive for their soft-pencil shading and angular lines, other notable young cartoonists include Alex Gregory, 33, known for his spare, digital-looking drawings; Marisa Acocella, 43, who draws frizzy-haired, Fendi-bag-carrying fashionistas; Drew Dernavich, 35, whose cartoons look like woodcuts; and Eric Lewis, 33, whose sharp line drawings often accompany absurd captions. In one, Albert Einstein lies in bed smoking a cigarette with a scowling woman, saying, "To you it was fast."

While younger New Yorker cartoonists are not above a good lawyer or cat joke, their work typically contains more references to drugs, sex, e-mail and contemporary social mores. The cartoons of Chad Darbyshire, 32, who signs his cartoons C. Covert Darbyshire, for example, often deal with the stresses of contemporary childhood. In one, a child opening a present before his suit-clad father says, "Tell your assistant it's perfect."

"Each generation has to speak to its own generation," Mankoff said. "It's got to be in its own time -- maybe not just making a joke about body piercing, but participating in body piercing."

To get his new voices, Mankoff has selected an eclectic bunch. Diffee, for example, grew up in Texas and North Carolina, the son of an airline pilot, and went to college at the conservatively religious Bob Jones University, with hopes of becoming a missionary.

Other young New Yorker cartoonists are more cosmopolitan. Carolita Johnson, 39, who has had four cartoons published, returned to New York recently after 15 years in Paris, where she was a model and studied medieval literature. (Her specialty was the hysterical visions of medieval nuns.) Lewis, a Columbia graduate now studying art at the Rhode Island School of Design, is the son of Dorothy Otnow Lewis, the Yale psychiatrist known for her research on serial killers. And Marisa Acocella -- no relation to the New Yorker dance critic Joan Acocella -- is engaged to Silvano Marchetto, the owner of the trendy downtown restaurant Da Silvano, whose patrons serve as inspiration for many of her cartoons.

There is no set method for recruiting cartoonists, Mankoff said. Diffee got in the door when he won a contest, sponsored by The New Yorker and the Algonquin Hotel, with a drawing of a couple in a hotel room, staring at the "Do Not Disturb" sign on the back of their doorknob.

"Oh, great," the man says. "I guess we're stuck in here."

Lewis got his chance when he met Mankoff's assistant on a cigarette break in front of The New Yorker's old building on 43rd Street, also the offices of Martha Stewart Living, where he was working as a designer of garden tools. Emily Richards, 34, a fact-checker at the magazine who has published a single cartoon there, was discovered when Mankoff absent-mindedly picked up a folder of her sketches in the office.

Mankoff looks at most of the 1,000 or so unsolicited submissions he receives each week, and makes a point of being accessible. "My policy is I'll see anybody," he said.

The move to bring in new talent to the magazine is not tension-free. Cartooning for its pages is a zero-sum game; The New Yorker publishes only 18 to 20 cartoons a week, for which it pays an average of US$675 each. Space and money taken by up-and-comers is lost for the old guard, who are popular with many readers.

"It's a very tricky thing," Remnick said. "You want to make sure that people who have been around for a while or even longer than a while are appreciated. At the same time, you need to encourage. Life keeps charging on."

For the most part, older and younger cartoonists get along, but the wait outside Mankoff's office on Tuesdays -- for what is known as "the look" -- can be tense. The older cartoonists never show others their batches, a tradition established years ago out of paranoia, when the stop at The New Yorker was just one of many that cartoonists made on Tuesdays, along with calls at Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post. These days, with few places to take rejected work, members of the younger crowd are quick to show off their best bits to their peers.

After Mankoff has made his picks, the cartoonists head out for a friendly and often boozy lunch at a French restaurant. Once a month, young and old cartoonists join forces for the Rejection Show, a monthly event at a Midtown performance space, where they display work that didn't make the cut.

Mankoff said he regularly prods his charges to improve their drawing skills, sometimes bluntly. At last week's meeting, he asked a younger cartoonist why all his cowboys looked as though they were riding dogs. Mankoff tries to teach younger cartoonists to get over what he calls the "euphoria of their own ideas," and to produce a workmanlike quota of at least 10 cartoons a week. "The new breed is nothing if not lazy," he said.

He has his personal quirks as well. In addition to the prohibition against fedoras, puns are out, and so is the image of a woman wielding a rolling pin. That doesn't work, he tells cartoonists, because no one has rolling pins anymore. Gross, a contributor for 35 years, said most cartoonists see such strictures more as challenges than limitations. William Shawn, the late New Yorker editor, once announced a ban on cartoons involving desert island scenes. The next week, Gross said, the cartoon editor was deluged with desert island gags.

For now, Diffee said, he plans to abide by Mankoff's rules. He figures his career is safe, he said, "unless hats come back in style."

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of