Every doctor recognizes them.

The man who discovers a bruise on his thigh and becomes convinced that it is leukemia. The woman who examines her breasts so frequently that she makes them tender, then decides that the soreness means she has cancer. The man who has suffered from heartburn all his life but after reading about esophageal cancer has no question that he has it.

They make frequent doctors' appointments, demand unnecessary tests and can drive their friends and relatives -- not to mention their physicians -- to distraction with a seemingly endless search for reassurance. By some estimates, they may be responsible for 10 percent to 20 percent of the US' staggering annual health care costs.

Yet how to deal with hypochondria, a disorder that afflicts one of every 20 Americans who visit doctors, has been one of the most stubborn puzzles in medicine. Where the patient sees physical illness, the doctor sees a psychological problem, and frustration rules on both sides of the examining room.

Recently, however, there has been a break in the impasse. New treatment strategies are offering the first hope since the ancient Greeks recognized hypochondria 24 centuries ago. Cognitive therapy, researchers reported last week, helps hypochondriacal patients evaluate and change their distorted thoughts about illness. After six 90-minute therapy sessions, the study found, 55 percent of the 102 participants were better able to run errands, drive and engage in social activities. Antidepressant medications, other studies indicate, are also proving

effective.

"The hope is that with effective treatments, a diagnosis of hypochondriasis will become a more acceptable diagnosis and less a laughing matter or a cause for embarrassment," said Dr. Arthur Barsky, director of psychiatric research at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston and the lead author of the study on cognitive therapy, which appeared in the March 24 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Almost everyone has inexplicable physical symptoms from time to time, and many people experience a moment of worry that their odd rashes, bumps or pains are signs of real trouble. But an official diagnosis of hypochondria, according to the American Psychiatric Association, is reserved for patients whose fears that they have a serious disease persist for at least six months and continue even after doctors have reassured them that they are healthy.

In patients with hypochondria, experts say, ordinary discomforts appear to register more intensely than they do for other people.

Looking in

"The person's nervous system is like a radio whose volume has been turned up so high, the background static becomes intolerable," Barsky said.

Researchers have found that hypochondria, which affects men and women equally, seems more likely to develop in people who have certain personality traits. The neurotic, the self-critical, the introverted and the narcissistic appear particularly prone to hypochondriacal fears, said Dr. Michael Hollifield, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of New Mexico.

As many as two-thirds of hypochondriacs also have other psychiatric disorders. Studies suggest that 40 percent suffer from major depression, 10 percent to 20 percent have panic disorder, 5 percent to 10 percent have obsessive-compulsive disorder and some have generalized anxiety disorder.

The fear of illness comes in varying degrees of intensity. Hypochondria may be mild, a faint background noise, or so intense it drowns out all other thoughts.

"It can be hard to sleep or think of anything else other than your hypochondriacal fears," said Dr. Brian Fallon, an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia.

In some cases, patients become so fearful about their imagined illness that they make the symptoms worse.

"A headache that you believe is due to a brain tumor is a lot worse than a headache you believe is due to eyestrain," Barsky said.

For the hypochondriac, a nagging worry often becomes panic, which then leads to further symptoms.

"Because patients are anxious, their heart starts to race and they become dizzy," said Dr. Jonathan S. Abramowitz, a clinical psychologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who treats patients with hypochondria.

The new symptoms cause further anxiety, and the cycle continues.

In the most extreme cases, patients can worry to the point that they develop delusions or become almost entirely disabled by fear.

"They become so afraid of what is going on with their body, they become shut-ins," said Hollifield of the University of New Mexico. "They think that anything they do is going to rile their body."

Yet hypochondria does not typically lead to suicidal thoughts, said Dr. Don Lipsitt, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard, if only because people who fear illness also fear death. "These people have a tendency to live out a pretty healthy life," he said. "They nurse themselves. They mother themselves in a sense."

Hypochondria has a long and colorful history. In the 18th century, James Boswell wrote a weekly magazine column, "The Hypochondriack," describing his obsession with personal health. In the 19th century, Charles Darwin worried over unexplained palpitations, fatigue and trembling in his fingers, which flared up when he had to discuss his new theory of evolution. Proust was so protective of his health that he kept himself wrapped in layers of overcoats and mufflers.

Looking out

The ancient Greeks used the word "hypochondria" to describe symptoms of digestive discomfort, combined with melancholy, that they thought arose from the spleen and other organs in the hypochondrium, the region under the rib cage. The disorder was thought to occur only in men. In women, unexplained symptoms were attributed to hysteria, a dislocation of the uterus.

This view prevailed for 2,000 years, until physicians in the 17th century realized that hypochondriacal fears probably originated in the brain, not the body.

Yet doctors could offer little in the way of treatment beyond the traditional strategies of bleeding, sweating and inducing vomiting.

In the 20th century, Freud recognized that hypochondria had both psychological and physical properties. Because of this, he had little interest in the subject. Other doctors held that the suffering of hypochondriacs must be "all in their heads."

However, many experts now say that discounting patients' symptoms only makes matters worse.

"When you think about it, it's the ultimate hubris for a physician to proclaim that a patient's symptoms are not real," Fallon of Columbia said. "If a person is experiencing something, it is real, whether or not you can explain it physiologically."

Still, it is psychiatry that offers patients the best hope of getting control of their anxiety. That often leads general practice doctors into a delicate dance, as they try to find ways to refer patients to psychiatrists without offending them.

Just mentioning the word hypochondria to a patient, Barsky said, can cause trouble.

"That comes across as, you're telling me I'm a faker, the malingerer, that it's all in my head," he said. "It's tremendously pejorative."

As a result, some experts have suggested that doctors drop the word altogether, substituting the term health anxiety, which has fewer negative connotations.

If a name change can allow more patients to accept their problem, the logic goes, perhaps more patients will seek treatment. Cognitive therapy, as demonstrated by Barsky's study, has proved surprisingly effective in helping patients who read into every ache and pain a portent of disaster.

In the study, the patients, whose fixation on illness had greatly interfered with their daily lives, did not see their symptoms disappear. But they did learn to pay much less attention to them.

The therapy taught the patients to re-examine their assumptions about the symptoms.

"We talk with patients about other possible explanations for their headaches, their tension or their lack of sleep," Barsky said.

The therapists, who included psychologists, social workers and nurses, also coaxed patients to temporarily suspend some of the usual ways they reassured themselves, like checking the Internet for health information, taking their pulse or blood pressure and scheduling appointments with doctors.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

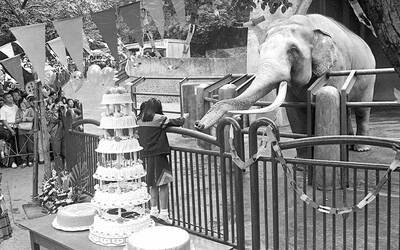

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

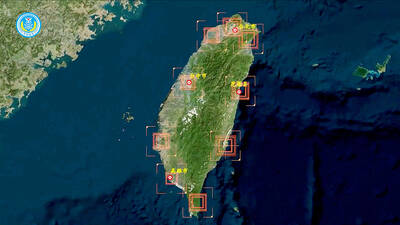

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger