The first time I met Mark Caltonhill he was blowing water up his nose and out of his ear, or perhaps it was the other way round. He was warming up an audience before an English-language theater performance and friends told me that not long before he'd been hanging from an art gallery ceiling regaling the passers-by with jokes. Now here he is in the public eye again, this time as the author of a book on the religious life of Taipei.

There's no doubt that Caltonhill has a remarkably versatile talent. We've heard of Zen monks playing practical jokes which carry a profound significance, but this is something rather different. Caltonhill is versatile because his theater performance was very funny and this book is remarkably informative, enlightening and even scholarly. He has many different strings to his bow.

The first thing to strike you on picking the book up is the photographs. There are many, most of them taken by the author, and they are a delight, throwing a varied and often unexpected light on his subject. Who would have thought a picture of a young girl in a denim jacket against a sky of blue and white could be so relevant! "A Taipei citizen checks out the `wind and clouds' for possible rain but not for the results of future wars as her ancestors might have done," runs the caption, and all is explained.

I'm not being facetious. This is a genuinely enjoyable book. The problem when writing such things is essentially one of tone. Present your material too matter-of-factly and it seems banal and boring. Present it with too prominent a sense of humor and the devout people it describes will be up in arms. Caltonhill steers a course between these two attitudes and gets it just right.

As a non-Chinese he is clearly unlikely to urge on other non-Chinese readers the reliability of divination and fortune-telling, or how to protect yourself effectively from the perils of the Ghost Month. On the other hand, this book is published by the Taipei City Government and the religious practices of Taipei's citizens must therefore be described with sympathy and a generous measure of respect. Caltonhill is notably successful in performing this difficult balancing act.

When someone graduates in Chinese from a major UK university such as Edinburgh you expect him to be capable intellectually. And so this author proves. He summarizes the many different traditions that combine to create Taipei's modern religious scene effortlessly. He describes the ceremonies that accompany birth, marriage and death, and yet manages to grace such momentous events with a light touch which, without ever being in the least bit sarcastic, makes them interesting and easy to take on board.

A book of this kind, in other words, could very easily be portentous, patronizing and even offensive. This is none of these things. It's interesting without overburdening you with excessive information, and entertaining without ever approaching being irreverent.

The range of the book is also admirable. You go from tomb-sweeping to vegetarianism, dragon boats to passing exams, green mountains to blue-eyed barbarians. You want to know about crouching tigers, bribing the kitchen god, immortality, or the Lunar New Year? It's all here.

One of the more bizarre experiences foreigners experience in Taiwan is being asked what their blood-type is. I can never remember mine, but this book is well aware of the cult, noting in passing that interest in the subject as a source of information for character-reading is a recent innovation.

There are such incidental insights everywhere in this eminently painstaking book. Tibetan-style Buddhist funerals are gaining in popularity, you learn. The English phrase joss money derives from the Portuguese word deos, meaning god. And the mischief traditionally practiced in the bridal chamber at a Chinese wedding originated from the desire to trick malign fox spirits into thinking there was no need to plague the newly married couple because it had already been done. Or so it's claimed -- a more mundane motive is hard not to credit.

One risk with a book like this is that it'll become a dreary recital of traditions that, though still practiced, are a long way from the world modern young Taipei people live in. Caltonhill avoids this pitfall too, not exactly by irony but instead by a kind of tartness. "One of the strangest sights in Taipei is that of ambulances speeding dying people away from hospitals," he writes. He goes on to explain the reasons, calmly and without bias. It would have been easy for someone with less poise to expatiate on how superior this is to the characteristic Western experience of death in an intensive care unit, far from friends and cultural traditions. It would be equally easy for someone to point to the paradoxical mixture of high-tech and spirit-worship in the Taiwanese world. But this author does neither. He just states and explains. This is a great virtue.

We all bring our own cultural assumptions to a foreign place, and as a result see it wrongly -- see it, in other words, merely as an imperfect version of our own country. Nothing could be more mistaken. Read this book and Taiwan and Taipei will seem different places, and much closer, probably, to how they really are.

There is a short section on imported religions. There isn't room for much detail, but still Caltonhill manages to include some insights -- such as that it was the expulsion of Western missionaries by the Japanese in the 1940s that led to the indigenization and autonomy of Taiwan's Christian churches.

Taiwan's reputation, in Hong Kong and elsewhere, is strong on two things -- ghosts and eating. This book fills you in on the former most comprehensively. Perhaps Caltonhill can now be persuaded to undertake a book on the equally wide range of Taipei's food. But one thing is certain -- Private Prayers and Public Parades will be a hard act to follow.

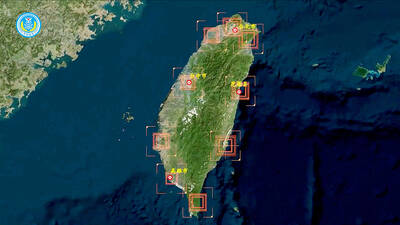

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On