At the Bom Jesus farm in Brazil, a slave laborer was told to treat the cuts he got hacking down thorny undergrowth by rubbing them with salt and urinating on them and then to keep working.

The stories told by Valdeci Alves Ciqueira de Oliveira and 21 other workers found in a government raid on the farm left no doubt that Brazil's feudal slavery traditions are alive in pockets of its poverty-stricken northeast.

PHOTO: REUTERS

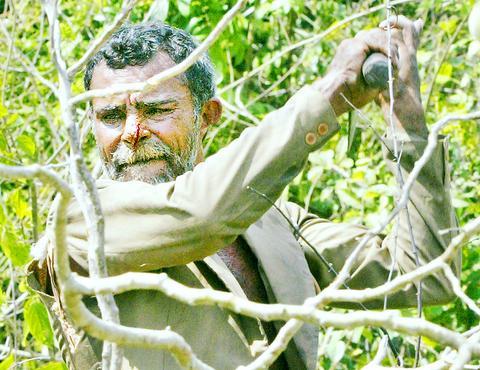

As government inspectors and armed federal police descended on the farm in Maranhao state, the bedraggled workers emerged one by one from the bush which they had been slashing to turn into cattle pasture.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Brazil's government estimates there are 25,000 indentured servants in this country, which imported more African slaves than any other before abolishing the practice in 1888. They are lured into their predicament with the promise of jobs on isolated farms and once there find themselves unable to pay off debts amassed for tools, clothing and sundries.

The inspectors who arrived at Bom Jesus belong to one of five federal government teams that scour Brazil's vast, isolated interior to liberate peasants working in slave-like conditions, relying on human rights groups for tips.

So far this year, they have freed 3,160 workers, compared to 2,156 in all of last year. President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, himself from a northeastern state where the practice formerly existed, has pledged to eradicate slavery for good.

At Bom Jesus, like other farms including one in Bahia state where a record 800 workers were liberated in August, there are no chains or whips. But the laborers know and fear the man who has turned them into indentured slaves.

The cat

"He is evil," said Francisco Borges de Souza, a 47-year-old slave laborer, sweating heavily and bleeding from his nose as he clutched his scythe with a deformed hand. The temperature was easily 400C.

Borges was talking about the man known to farm workers in Brazil's lawless ranching frontiers as the "gato," or cat -- a sort of foreman, often armed, who is contracted by a farmer to provide laborers to do work like clearing fields or setting fences. And then he exploits them.

"The cat doesn't let anybody leave without paying their debts," said Ciqueira de Oliveira, 46. "Nobody ever settles their account here."

The cat was not there when the inspectors arrived. But his presence was clear in the squalid makeshift shelter of wooden poles and plastic canvas where the workers live in a dusty, sun-scorched gully.

On the earthen floor near their grimy food -- dry beans, rice and fly-infested pig fat -- sat two wooden boxes. They contained tools, cigarettes, boots, soap, sweets and other items that offer the men some normality in their miserable lives.

The workers have to pay for everything, at inflated prices, except meals and lodging. If they have a day off, they pay for their meals too.

"They were treated like animals," said Fabio Leal Cardoso, a government prosecutor on the team.

"This we can really describe as being like slavery," said Claudia Marcia Brito, who heads it.

The inspectors meticulously interviewed every worker. Most had received no pay for up to six months and many put their thumb print on the declaration because they cannot write.

Won't sleep in a mansion

The inspectors returned to their trucks and drove 5km down a dirt track to the farm house to see farmer Marcos Antonio Araujo Braga. Two armed federal police agents stayed with him while the inspectors talked to the workers.

Although Braga hired the cat to manage the workers, he is responsible for what happens on his property, Brito said.

On Braga's patio, two dachshunds played and his wife offered cool water to the inspectors.

Braga was told he had broken the law and must pay the workers arrears of up to US$700 each, a small fortune for Maranhao's dirt-poor peasants. He also faced a large fine.

The owner said he offered to let workers sleep in a farm house but they refused. He said there were no documents on their employment because "most of them are illiterate."

"You can give a house or a mansion to those people and they will still sleep in a hammock," he said. "Those people are used to bad food, but even so I killed a cow and gave it to them. Thank God, this farm Bom Jesus is more than just a name."

Braga said the information provided by the workers was not true but promised to improve their conditions.

The inspectors say eradicating slavery is not just about raiding farms, but of changing cultures which have existed in Brazil's isolated regions for centuries. It often goes hand in hand with Amazon deforestation and lawlessness.

"You have to remember that things have been like this for 300 years and then suddenly the state turns up with an apparatus," said prosecutor Leal Cardoso. "Things don't change overnight."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the