Sometimes it is extraordinary to observe the difference between French and Anglo-Saxon literary tastes and attitudes.

Here is a novel, first published in French, written in the simplest imaginable prose, as slender and yet as strong as a hare's skeleton. Some of its chapters are no more than a page long. Yet this frail thing is adorned with scholarly footnotes. The combination of the whittled-down style and the footnotes is something hard to imagine originating from a London or New York publisher. Yet here it is now in English translation.

The book is set in Manchuria in the 1930s, during the Japanese invasion. The two narrators of its 92 chapters alternate. The odd-numbered chapters are told by a 16-year old Chinese girl, fearful, like everyone else, of the invading soldiers' advance. The even-numbered ones are told by a young officer in the Japanese army.

Sex is prominent in the lives of them both. The girl, who is descended from a line of nobility whose women breast-fed the Manchurian emperors, fights off the unwelcome attentions of a relative, then gives up her virginity to one of two students she meets, both of whom are in love with her.

And the officer, anxious to prove his manhood (as he perceives it), strains and struggles, both on the battlefield and in the arms of the alluring Manchurian prostitutes.

The two principal characters are eventually drawn together by the girl's displays of skill at the game of go in her home town's public square, and the young officer's determination to discover what lies behind this seemingly impossible feat of female

supremacy.

The construction of this subtle and elegant, though sometimes sensational novel at first looks as if it's going to be plain sailing. Before long, however, the stories become so engaging that it's hard not to skip the next chapter in order to find out what happens after the one you've just finished. But then, as both stories become equally gripping, you're forced to follow the author's intention and switch regularly from one story to the other. It's a practice that increasingly pays dividends as the dramatic end of the novel approaches.

The author, Shan Sa, is 29 and, though born in Beijing, has been living in France since the age of 18. This is her third novel and all three books have already won for themselves important French literary prizes.

What makes this novel so vivid is that the details of life -- the pirouetting of a carp in its sunlit tank, the jokes played on each other by the Japanese officers -- serve to join the two groups of people together. Certainly we enter imaginatively into the lives of both parties. But the political reality is that they are fighting a war, and you know from the beginning that something terrible is eventually going to happen. This shared sense of the immediacy and the transience of life is what in the final analysis makes this novel so strong, so intelligent, and so moving.

There are many other themes in this deceptively simple book. The Japanese officer, for instance, as a child had a Chinese nurse, and she taught him Chinese stories, as well as making him fluent in Mandarin. In this way, the historical influence of Chinese culture on Japanese life is subtly introduced into the book, an influence that becomes ever more significant as the Japanese soldiers advance on their brutally oppressive mission into Manchuria.

But this Chinese background of the officer's also serves another purpose. It allows him to disguise himself in Chinese clothes and go down to the town square to play go against the locals. In this way he comes up against the narrator of the other half of the story.

There are all sorts of other intriguing complexities as well. Go is a game of battle, and so acts as a metaphor for the historical

situation in the story. And is the officer in reality being sent into the town to act, even without his at first being aware of it, as a spy? A further division of loyalties occurs when it transpires that the two student friends of the go-player are secretly involved in a planned insurrection against the Japanese.

There are horrors too -- torture, executions, and betrayals both political and romantic. But there's also a sense of humor. The girl, thinking she's pregnant, visits a physician whose room bears the following advertisement: "Doctor famed over the four seas for his heavenly gift for bringing back the springtime of your life. Specialist in chancre, syphilis and gonorrhea."

And in a sense this is an old story -- soldier in love with girl from the country his army is determined to pulverize. Even so, it is told here with consummate economy and skill.

With its peacock-feathered hats, its scarlet brocade edged with gold, and the sunset throwing its crimson cloak over the hills, this novel has a great deal of stylishness and color. And in addition to drama, historical interest, and a wrenching love story that doesn't preclude plenty of frankly-depicted sex, it also contains an evocation of the distinct ethos of the Manchurian people and their region.

This book, in other words, is that enviable thing, an ambitious literary product that is all set to be a popular best-seller of its day. It isn't too far-fetched to compare it to Romeo and Juliet in the qualities it so effortlessly combines.

There's an interesting error on page 250 -- "This mad woman is steal jealous!" -- which proves that Adriana Hunter's excellent English translation was in fact dictated to a scribe.

North-eastern China in the 1930s was undoubtedly far more poverty-stricken in reality than it appears here. Nonetheless, you'll have to look far and wide to find a better new novel on an East Asian subject than this finely crafted story, satisfying as it is on so many different levels.

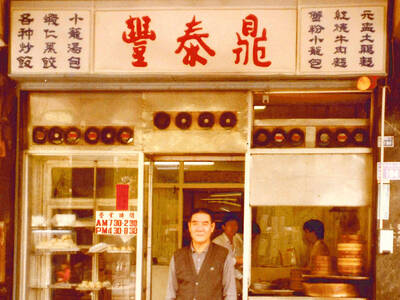

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern