Love them or loathe them, with the Mid-Autumn Festival only six days away mooncakes are everywhere. Be it at the local mom and pop corner store, the 7-11 or the glitzy new European supermarket, the sights and smells of the round pastry covered cakes are impossible to avoid.

Traditionally filled with red or green bean paste and now crammed with every conceivable form of filler from kiwi to egg custard, the mooncake has come a long way since the first one rolled out of the oven of an enterprising revolutionary by the name of Chu Yuan-chang (朱元璋) during the Yuan Dynasty (1279 to 1368).

Looking for a way to incite the Han people into revolt against the much-despised Mongols without alerting them, Chu, with the help of his confidant, Liu po-wen (劉伯溫), circulated a rumor that a plague was ravaging the land. The only way to prevent a disaster was to eat special mooncakes that were distributed by Chu and his fellow revolutionaries.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

Distributed solely to Han people, on the outside the cakes looked normal enough. Inside, however, lay a message giving to the day on which the anti-Yuan insurrection was to begin.

Reading "revolt on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month" the date has since become one of the most important holidays in the Chinese calendar, second only to the Lunar New Year itself.

While mooncakes are no longer used to incite rebellion -- nowadays they represent family unity and perfection -- there has been a revolution in the way in which they are manufactured and packaged.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

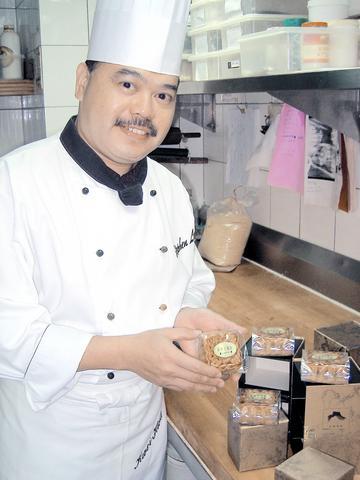

"When I was growing up in Hong Kong there were only a couple of varieties of mooncake. You had the choice of red bean, green bean or lotus paste," said Stephen Lo (盧偉強), an executive chef at Taipei's Imperial Hotel. "And they came in a simple cardboard box."

Traditional Cantonese, Taiwanese and Soochow-style mooncakes with their bean paste and egg yoke fillings continue to be popular with older generations, but over the past decade bakers have been forced to forgo tradition and move with the times.

Constantly searching for inventive ways to interest a younger generation more in-tune with Western foodstuffs than their parents, bakers now stuff their crusty pies with some highly unusual fillers.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

"If I'd made a kiwi mooncake in Hong Kong as recently as 10 years ago I would have been laughed out of the kitchen," said the chef. "Now I'm forced to come up with new and inventive fillings every year."

Some of the more popular flavorsome additions to the mid-Autumn treat in recent years have included ice cream, egg custard, ginseng, rose, green tea as well as kiwi and XO brandy. Due to current trends in juice bars, this year has seen a rise in the number of vegetable mooncakes, with both tomato and carrot paste flavors leading the way.

While tomato mooncakes are proving a hit not all "fashionable" additions to the ever-increasing list of mooncake flavors have fared so well. Some have surprisingly fallen flat with the mooncake buying public.

PHOTO: GAVIN PHIPPS, TAIPEI TIMES

"We made coffee and chocolate mooncakes a couple of years ago and we expected them to prove pretty popular, with Taiwan's fascination with coffee shops being at an all time high," said Eddie Liu (劉冠麟), assistant director of food and beverage at the Far Eastern Plaza Hotel. "Neither flavor worked, however, and we won't be using either of them ever again."

Coffee and chocolate may have proven disastrous, but some of the more outlandish flavors now available have proven surprisingly popular, especially to those with money to burn. Sharks fin, birds' nest and abalone-flavored mooncakes can only be found at only a handful of the 200 mooncake stores in Taipei, yet all three flavors sell well regardless of price.

The costliest of these varieties is abalone, one kilo of which will set you back roughly NT$40,000. According to Lo, however, the use of such ingredients and paying such vast amounts for such mooncakes is quite absurd.

"It's a bit of joke really. Birds nest and sharks fin are both tasteless ingredients unless prepared in a soup with a rich stock. And abalone, well, that's just stupid," Lo said. "People simply buy them because they are expensive items. It's certainly not for the taste."

Toying with mooncake fillers may now be readily accepted by chefs, but there has been heated debate about the issue. While chefs such as Lo tolerate the use of fashionable fillers, mention adding egg or butter to the traditional oil, flour and water based pastry and you'll rouse his ire.

"I know a lot people have taken to experimenting with more Westernized pastries, but it shouldn't be done," Lo said. "It's mooncake season, not pastry season!"

Along with the changes in mooncake production, packaging has become as important, if not more important than the cakes themselves. Manufacturers now work on the premise that mooncake boxes have to be more than simply a form of packaging.

"Customers now like to purchase something that has other uses. A box that is simply a box is not something you'd want to keep," Lo said. "Packaging that has other uses means that it will not be tossed out with the garbage as soon as the cakes have been eaten."

The multi-purpose packaging Lo's hotel has opted for this year has four mooncake-sized drawers and resembles a jewelry or kick-knack box. The nation's most popular packaging designs, however, continue to be those made of metal/tin or wood.

Although not available in Taiwan, the most outlandish design this year has been produced by a hotel in Shanghai. Designed to look like an old fashioned music box and play a tune when opened, the special packaging costs NT$2,500 -- without the mooncakes.

"It's a question of face sometimes rather than what is inside," said Liu. "I mean, even if the person doesn't particularly like the mooncakes, they can't fail to impressed by a swanky box."

This is something that this reporter discovered to be true when, on taking home a fancy box filled with traditional mooncakes, I was not thanked for the cakes themselves, but instead was asked, "Can I take them [mooncakes] out and have the box?"

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of