Retired builder Ivan Plotnikov always regretted he wasn't born Richard the Lionheart.

At age 4, he promised himself and his parents that he, like England's warrior king, would have his own castle someday. At age 7, he drew out a plan. And at age 19, he robbed a bank in a failed effort to get the money to pay for its construction.

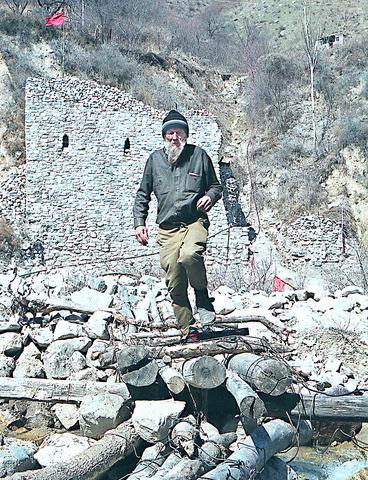

PHOTO: AP

Yet, 35 years later, a half-finished gray stone bastion stands amid rickety little weekend cottages on the bank of a mountain river in the picturesque Aksay Gorge outside Kazakhstan's biggest city, Almaty.

Fifteen meters tall and about 10m wide, it looks like a small medieval castle from afar. Only the freshly laid rocks at the top give away its true age.

"Are you tourists, journalists or theater lovers?" the heavily bearded Plotnikov calls out to visitors crossing a small footbridge spanning the river.

He's got a card certifying that he's an invalid, and another that proves his proud membership in the Communist Party. He got the latter only recently -- in Soviet times, when the party accepted only the cream of the crop, a convicted bank robber who did time in a psychiatric ward couldn't make the grade.

"I will keep building this fortress until I die, like Lenin and Stalin built communism," Plotnikov tells his visitors.

Small beginnings

He began building the castle in 1983, earning a living at construction sites during the week and spending weekends in the gorge. Since going on a disability pension five years ago, he has devoted most of his time to raising the bastion.

He must wait out the harsh winter at his two-room apartment in Almaty, where utility bills eat up 5,000 tenge (US$33) of his 5,900-tenge (US$39) monthly pension. But when the cold begins to ebb, he camps out at the castle, which is outfitted with a cot, a small heater and a fireplace. He draws water from the river and takes a weekly hike to the closest village, 5km away, to buy tea, bread and the few other staples he can afford.

"The apartment eats up all my money; there's nothing left for cement," Plotnikov laments. "So I hire myself out to cottage-owners, helping dig potatoes. Sometimes they give me money, but more often they give me food or cement."

Plotnikov wrestles rocks weighing up to 50kg up from the river for the walls. He figures that over the 20 years he's carried about 800 tonnes up the bank.

He doesn't know just how the idea of building a castle came to him. He only remembers that from early childhood, he would close his eyes and see a stone bastion with little windows, arches and a flag -- a red flag. He says family legend has it that his grandmother and grandfather were Russian nobles.

"I was born in China in 1949," Plotnikov says. "My mother told me that she and her parents fled Russia on the eve of the revolution."

Childhood dreams

When Plotnikov was 4, his family returned to Russia. They lived for a time in the Siberian city of Omsk, then moved south to Almaty, in the then-Soviet republic of Kazakhstan.

"I was already getting on my parents' nerves with my knights, fortresses and chain-mail shirts," Plotnikov recalls.

In school, when he was 7, he got a top grade for a mock-up of a castle. In a later class, he drafted a construction plan. He still carries the yellowed drawing in his chest pocket.

"My parents refused to finance my project. That's when I decided to rob the savings bank," he says.

"On Aug. 13, 1963, I forced my way into an Almaty branch with a sawed-off shotgun. I pointed the gun at the cashier. She gave me five rubles. That's all she had, because the bank had just opened."

He was caught immediately. The investigators were unmoved by the story of his dream of building a castle. They took it as the ravings of a lunatic and he was sentenced to two years in a psychiatric hospital.

"Those were awful times. To this day I don't know what they cured me of. Maybe I really am sick," Plotnikov says.

He made his first stab at building a castle near Almaty, but there were too few rocks there and he had to drag them from far away. Then some friends showed him the site in the Aksay Gorge.

After two decades, he's built about half the bastion of his dreams. According to his plan, it should have two towers with a round arch in the middle.

"I won't have time to finish it before I die, but I hope someone will continue my work," Plotnikov says. "Maybe once it's finished, someone can open a restaurant here.

"There's a saying that a man should achieve three things before he dies: build a house, plant a tree and have a son. I don't have children, but I'm leaving a fortress. And maybe someone will remember Ivan."

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On