It's now almost 20 months into the Nasdaq crash and the index is still staggering, reeling and continuing to slide. But the fact that the world's leading technology stock market is still in the late stages of an Icarus plunge hasn't altogether killed belief in the Internet revolution.

Early last week, a techie friend I'll call Q-Bert told me about the ongoing financial implosions taking place in a local Internet company he may or may not still be working for. It had only been four weeks since he'd first given me the company business card. I'd bumped into him and his boss, a 20-something female CEO, at the B-list celebrity studded opening of Saloon -- the new in-crowd bar on Hsinyi Road invested in by Taipei nightlife impresario Turtle and skatewear king Jimi Sun and with the involvement of their pal, pop singer/DJ Chang Cheng-yue (

PHOTO COURTESY OF MOCA

By last Monday, the company's offices were empty and Q-Bert had its computers piled in his living room, from which he was also running the company server. Q-Bert hadn't been paid for two months and didn't expect his salary anytime soon.

And in spite of all this, Q-Bert, who told the story while drinking beer, watching baseball and talking about drumming up freelance gigs, could laugh and half-seriously say, "But hey, who knows? We might be back. We are after all an Internet company."

So even after the great tech crash of 2000, which was supposed to have put a pin to the over-inflated promises of the wireless and the digital, there's still a lot of the popular optimism about technology. Q-Bert is pretty normal for well educated first worlders; he understands the important practical realities, but also invests a fair amount of time in cultural pursuits: music, art and other areas of abstract thought. Rightly or wrongly, it's in the cultural sphere that a lot of the residual tech optimism is rooted, especially among theorists, artists and club kids, who aren't constrained by the harsh pragmatism of the business world.

A critique of "techno art" comes in Tech/No/Zone, a new exhibition at Taipei's Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) curated by Australian Ewen McDonald. The show's goals are sound: to show how "technology appears revolutionary and progressive" but in reality "can be restrictive, instilling uncertainty and fear"; and to provide an alternative that "concentrates on or celebrates what it means to be human."

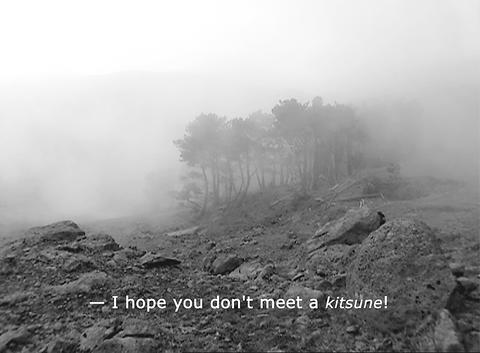

But while the show has a few (and only a few) very interesting works, only one of its twelve pieces is really successful in conveying this sense. That work is a marvelous video by the Portuguese artist Paoa Penalva titled Kitsune. For the 59-minute black and white video, Penalva fixed the camera in a single spot on a hillside, in one continuous take filming the rocks, glades, pine bowers and how their aspects continually change amidst the windblown clouds and mists that sweep up the slope. Other than this there is no action on camera, a feat in stupendous defiance of contemporary norms in film and television industries.

But Penalva's work does contain a beautiful and touching narrative, and truly it only happens in the mind of the viewer -- or perhaps "listener" is more accurate. You hear the voices of two old Japanese men who meet in the fog, telling stories of the old days and sharing tea. English subtitles -- mostly short, simple sentences -- appear at the bottom of the screen so that the story can be understood. The men begin by speaking of aging and of fear, but mostly they reminisce. They tell each other childhood stories of the kitsune, a fabled fox spirit parents used to scare their children with. Marvelously read, Kitsune captures the mystique of oral storytelling on video, and that is it's triumph.

But other than Penalva's Kitsune, Tech/No/Zone doesn't have much to make its case for human transcendence of the technological. Patricia Piccinini's Plasticlogy very interestingly simulates a forest with 50 TVs of oscillating, 3D, computer-generated trees -- the effect is so real it's easy to make a mistake at first. But in the good-bad debate over techno art, the piece could go either way.

While other works emphasize human realities (William Kentridge's animated film about the horrors of apartheid), deal with the random and non-technological (Rachel Lowe's film of scribbling on the window of a moving car), and show the falsity of simulacra (Dorothy Cross's film about fabricating, then smashing a glass eye), the critique seems unfinished. In short, Tech/No/Zone advocates the human without showing the value of the human, and that's where it's incomplete.

What: Tech/No/Zone

Where: MOCA, 39 Changan W. Rd. (

When: Until January 12, 2003

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how