The master and his student sat privately in the master's study. The master spoke, saying, "my student, you must flee to the outlying island. The new regime is certain of victory and with their victory will come a time where our religion and our martial art will be suppressed. To ensure the survival of the martial arts I have passed on to you, I want you to leave this land and journey to the island. There, hopefully, the art I have transmitted to you will be preserved from the coming darkness."

Sounds like a kung fu novel or maybe a plot to a Star Wars movie? It was an actual event. The martial arts master was Zhang Zhao-dong (

At the end of the Chinese Civil War, Taiwan became an important repository and conservatory of many aspects of Chinese culture such as painting, calligraphy, opera and traditional martial arts. In particular, Taiwan provided a refuge for practitioners of the three internal martial arts of tai chi chuan (太極拳), hsing yi chuan (形意拳) and pa kua chang (八卦掌).

Wang Shu-chin (1905-1981) was one of many martial arts masters who sought refuge in Taiwan following the Chinese Civil War. Over the years, the three internal martial arts that he brought with him have taken firm root in Taiwan and even expanded further to the US, Australia and beyond.

The internal martial arts that Wang Shu-chin practiced, tai chi, hsing yi and pa kua have a number of characteristics that link them together. They are each based in Taoist philosophy and emphasize the development and use of chi (氣), which is the term used in traditional Chinese medicine for the life force. The three internal martial arts seek to enhance the practitioner's overall mental, physical and spiritual state. These three martial arts can perhaps best be described as forms of moving meditation that, by their practice, give rise to martial ability.

Chi is central to the internal martial arts. It has been defined many ways and is an important part of many traditional Chinese arts. It is also an intrinsic part of traditional Chinese medicine. Scholars generally define it as the force or energy that animates all living things -- a kind of "elan vital." Chi has been likened to a flow of fluid or of electricity through the practitioner's body. Control and use of this energy is the goal of each of the three arts Wang brought to Taiwan.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS LIBRARY

These arts are referred to as "internal" because their training methods place an emphasis on the practitioner "looking inside" themselves and studying how their mind interacts with physical movements through breath and chi. Along with this is an emphasis on how their mind, breath and chi work together to create a very healthy, integrated individual.

But the arts are also extremely effective in combat, as revealed in many stories involving Wang Shu-chin. The source for most of the historical information about Wang is his student, Wang Fu-lai (

According to him, Wang Shu-chin was born in 1904 as the sixth son in a family of farmers living in a village about 32km from Tianjin City in northern China. His older brothers were content to farm, but Wang wanted to be part of a bigger world. So, with his parent's permission, he left home when he was 14 years old and traveled to Tianjin seeking fame and fortune. There he found work as an apprentice in an international trading company.

By the time of his arrival in Tianjin, Wang was already, as his student Wang Fu-lai puts it, "a man of impressive size and unusual physical strength." He was also very interested in martial arts and religion and began to search for martial arts instruction. By chance one day, a senior student of the famous martial arts master Zhang Zhao-dong came to the business where Wang worked. This chance meeting led to the then 18-year-old Wang studying under Zhang.

Under Zhang's instruction, Wang learned the two arts for which he would later become famous; pa kua chang and hsing yi chuan. Pa kua chang means "eight diagram palms" and refers to the eight core diagrams which make up the I-Ching (

The practice of pa kua chang consists of moving around in a circle while performing eight different martial arts techniques which use the palms to strike an opponent. Each of these eight techniques corresponds to one of the eight fundamental diagrams in the I-Ching. Maneuvering around to the side or back of the opponent, a practitioner strikes using one of the eight techniques. The art also emphasizes throwing the opponent -- much like in judo -- as well as various arm locks.

Wang could perform pa kua chang with dizzying speed, rapidly turning back and forth around the circle. Despite his size, he was able to move with incredible speed and agility, which he attributed to his study of the art form.

While pa kua focuses on circles, its sister art, hsing yi focuses on lines and linear attacks. Hsing yi consists of a set of five forms performed up and down along a straight line. These five forms correspond with the five elements in traditional Chinese philosophy: earth, water, fire, wood and metal. A hsing yi practitioner meets their opponent's attack on an oblique angle then overwhelms them with a series of rapid punches. The art, like pa kua, puts an emphasis on the use of chi and the integration of the whole body into a coordinated unit.

Hsing yi also trains its practitioners to be able to withstand the force of an opponent's blow. Wang was famous for his ability to withstand blows to any part of his body, excluding his head and groin. His "iron body" drew considerable interest from practitioners both in Taiwan and abroad.

In 1949, Wang's teachers sent him to Taiwan. They surmised -- correctly, history would prove -- that the change in China's government would likely lead to a suppression of martial arts. In order to ensure the survival of pa kua chang and hsing yi, Wang took them for safekeeping to Taiwan. He arrived in a fishing village in northern Taiwan in late 1949 and started his own rice business.

He also began to teach his martial arts and quickly gathered around him a number of dedicated students. Several years later he moved south to Taipei to open a rice shop. There Wang's businesses thrived and he became a fairly wealthy man.

He was also a man in demand. Word of his skill in martial arts spread and many wealthy people and politicians sought out Wang's instruction. While he considered his prominence flattering, given the political intrigues of the time, it was also dangerous. Distancing himself from this, Wang moved south to Taichung in 1952.

He continued to teach martial arts in Taichung where his reputation as a skilled hsing yi and pa kua practitioner preceded him. As number of established martial artists in the south of Taiwan sought to "test" Wang's abilities. Challenge matches in those days could be very rough affairs where the result was sometimes death. Wang successfully met all challengers and so cemented his reputation as Taiwan's most skilled hsing yi and pa kua fighter. Wang became known within Taiwanese martial arts circles as "the unvanquished."

His teaching too remains unvanquished. The martial arts association he formed in Taichung still teaches Wang's martial arts as he had. The association is now headed by Wang Fu-lai, who began studying under Wang at the age of 15.

After several years, Wang Fu-lai became the elder Wang's only personal student, meaning that he was permitted to live in Wang's house and be by Wang's side at all times. Today, the Cheng Ming Martial Arts Association is active not only in Taiwan, but in Argentina, Israel, the US, Japan and Australia.

This worldwide spread of the arts is evidence that Wang Shu-chin fulfilled his mission of preserving and spreading the martial arts that he had been entrusted with by his masters.

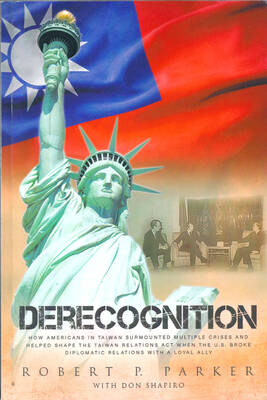

One of the biggest sore spots in Taiwan’s historical friendship with the US came in 1979 when US president Jimmy Carter broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government so that the US could establish relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Taiwan’s derecognition came purely at China’s insistence, and the US took the deal. Retired American diplomat John Tkacik, who for almost decade surrounding that schism, from 1974 to 1982, worked in embassies in Taipei and Beijing and at the Taiwan Desk in Washington DC, recently argued in the Taipei Times that “President Carter’s derecognition

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

You can tell a lot about a generation from the contents of their cool box: nowadays the barbecue ice bucket is likely to be filled with hard seltzers, non-alcoholic beers and fluorescent BuzzBallz — a particular favorite among Gen Z. Two decades ago, it was WKD, Bacardi Breezers and the odd Smirnoff Ice bobbing in a puddle of melted ice. And while nostalgia may have brought back some alcopops, the new wave of ready-to-drink (RTD) options look and taste noticeably different. It is not just the drinks that have changed, but drinking habits too, driven in part by more health-conscious consumers and

On Sunday, President William Lai (賴清德) delivered a strategically brilliant speech. It was the first of his “Ten Lectures on National Unity,” (團結國家十講) focusing on the topic of “nation.” Though it has been eclipsed — much to the relief of the opposing Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) — by an ill-advised statement in the second speech of the series, the days following Lai’s first speech were illuminating on many fronts, both domestic and internationally, in highlighting the multi-layered success of Lai’s strategic move. “OF COURSE TAIWAN IS A COUNTRY” Never before has a Taiwanese president devoted an entire speech to