On the evening of Nov. 18, 1997, McGill Alexander and his family were taken hostage by Chen Chin-hsing (

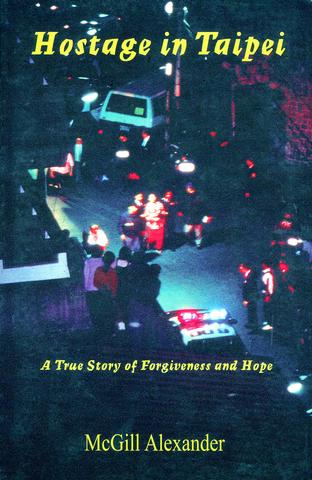

In December, Alexander released a book titled Hostage in Taipei through Cladach Publishing, a small publisher in California. The 317-page volume describes his personal experience of the night during which he and his daughter were shot and his wife and adopted infant were held at gunpoint for 20 grueling hours. Though the book has not yet seen an official release in Taiwan, it is available in English at some local book stores, including Eslite (

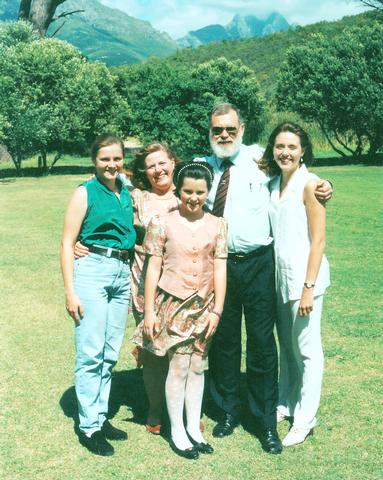

PHOTO COURTESY OF CLADACH PUBLISHING

Unlike the portrayal of events in the Taiwan media, Alexander's account does not dwell on the mania and bloodshed of those moments. Instead, he tells the tale of how the wickedest person he ever met turned to God. In the process, he levels some justified criticisms at both the Taiwan's police and media.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CLADACH PUBLISHING

Though I have never met Alexander in person, I know from news reports, photos and his book that he is a man of imposing stature. In the book Alexander mentions -- almost as an aside -- that his career has included "pathfinder training with the Israeli paratroopers, then commando training with the Chilean special forces and airborne exercises with the British Parachute Regiment in the Netherlands." In 1997, he was in Taiwan as a colonel, serving as South Africa's military attache. Now at the age of 53, he is a brigadier general, and his active duty continues. A significant portion of the book, he told me, was written while on active duty in KwaZulu-Natal, a region of South Africa that has been on the brink of civil war for nearly two decades.

Though he has been a soldier for much of his life, he does not display much of a rough exterior. Over the phone, his voice comes across as a warm baritone. He spoke eloquently in statements that were measured and even. If one dares judge from impressions, the impression he gave was one of gentle and tempered strength.

One can imagine that this man, a commander, was not at all comfortable tied up and at the end of a madman's gun. And despite his cool demeanor and rugged background, he could not help but admit that there was something especially dire about that night when Chen eased into his livingroom with a gun at the cheek of Christine, his 12-year-old daughter.

"I think there have been other occasions where I've probably been as close if not closer to death," said Alexander. "One doesn't know. When a bomb explodes almost next to you, how close were you to death? Or if a bomb lands right next to you and it doesn't go off, you again think to yourself how close were you to death ... but I've never been in a position where I was, one, so personally helpless and unable to do anything about it, and two, where my family was under the severest threat. I could do nothing. I had to sit and watch what was being done to them. I think that was the greatest pain, the greatest angst that I had to go through during that time."

It only took a few instants for Alexander, his wife Anne, daughters Melanie (then 22) and Christine and adopted infant son Zachary to become Chen's captives (another daughter, Shona, then 19, was in South Africa). The train of events leading up to that crisis was even more bizarre.

The saga of Chen's crime spree began in April 1997 when three men, including Chen, kidnapped, raped and murdered Pai Hsiao-yen (白曉燕), the 17-year-old daughter of a local singing star. During the eight month manhunt and crime rampage that followed, the trio were responsible for numerous atrocities, including the kidnapping and ransom of a local businessman and a triple murder at a plastic surgeon's clinic. Chen eventually also admitted sole responsibility for at least 18 rapes -- at times he told police there were more rapes than he could remember -- earning him the nickname the "Wolf of Chungshan."

When Chen took the Alexanders hostage on Nov. 18, he was the only one of the three bandits still alive. The other two had both committed suicide when cornered by police on separate occasions. Unlike his companions, however, Chen had a mission, that of freeing his wife, brother-in-law, and several other friends and relatives -- all of whom had been arrested by the police and summarily sentenced with long terms as accomplices to his crimes. In order to bargain with the police, Chen needed hostages, foreign hostages.

Unfortunately, it wasn't that simple. The entrance of the police into the hostage scenario can only be described as a black comedy of errors. Yet Alexander doesn't even portray it as such per se, probably because he is a man filled more with compassion than irony. His descriptive style, which he personally refers to as "report-like" and heavily influenced by his military background, devotes itself more to the scrupulous documentation of events. Yet the facts that he documents are beyond doubt, and even if he can forgive the actions of the police, he finds them hard to understand.

First, the police were slow to react as many false Chen sightings had occurred all over Taipei. Second, the first officers on the scene refused to negotiate or even speak with Chen, even though they spoke with the hostages briefly on a mobile phone. Then, the police enraged Chen by yelling at him from outdoors. Finally, they started shooting.

"As a military man, I can perhaps understand that the police had to do

something," said Alexander. "As a family man, I find it a little difficult to understand why the decision was made to assault first and negotiate later, rather than the other way around. My own experience in situations like that is that you first try to resolve it through negotiation, then resort to force and violence as a last resort."

In his book, Alexander also describes more subtle reasons for the turn of events. "The impression I gained was that Chen had no illusions regarding the certainty of a police assault. He also knew that the assault would not be a rescue attempt, but that it would be aimed at killing him. He therefore thought he had to use one hostage as a shield. That hostage would probably be sacrificed in the assault, but if it helped to repulse the police it would probably also bring them to their senses and force them to resort to negotiations."

In all, at least three volleys of gunfire were exchanged between Chen and the police. In the aftermath of the standoff, 160 shell casings were recovered from Chen's guns alone. And even after the police had ostensibly turned the apartment upside down looking for clues, the Alexanders continued to find spent shells in odd nooks and crannies of their home, including under the cushions of their sofa.

The most disturbing example of police misbehavior reported in Alexander's book comes not as blundering, but as direct misrepresentation. During the lengthy seige, when Alexander and his daughter Melanie were in the hospital being treated for bullet wounds (Chen had shot them accidentally while returning police fire and released them for treatment), his wife, youngest daughter and adopted baby son, meanwhile were still in the apartment and at Chen's mercy. At this time, some of Taiwan's top brass rushed to visit him in his sickbed. Then vice-premier John Chang (

Though it would have been easy for Alexander to do otherwise, his mention of this attempted cover-up assigns little or no blame to the perpetrators. During our interview, Alexander recounted his criticisms of police saying, "As long as it's seen as constructive criticism and hopefully something to build on, then I'll be quite happy. If I was to know that if this happened to anyone else in Taiwan that this kind of thing will be handled much better, then I will feel that I have achieved something."

When asked about improvements since the Chen Chin-hsing hostage crisis, assistant director of the Criminal Police Lin Kuo-tung (

Alexander is less restrained in his criticism of Taiwan's media, which he compares in his book to "a pack of African wild dogs -- perhaps the cruelest of all predators. The wild dogs of Africa tear chunks of flesh from their victim, running along beside the animal as it desperately tries to flee. In this way they will literally eat an antelope alive."

The metaphor specifically refers to the moments when Alexander and his daughter Melanie, both bleeding from bullet wounds, were impeded from reaching ambulances by throngs of photographers and reporters. "My daughter could have been dying when we were being evacuated," he said. "She was severely injured and she required very urgent medical attention. The fact of the matter is, if the bullet had been a few centimeters in one or the other direction, she would have probably bled to death before they could have got her to the hospital ? the media hemmed in to such an extent to get their photographs and to get their interviews, that it was totally impossible to get her into the ambulance. That was totally abhorrent."

But the media involvement did not stop there. For almost the whole night, Chen gave live radio and TV interviews over the Alexanders' telephone. Lin said that in the future, if a similar incident were to occur, telephone use would be monitored by police.

Tai Chung-ren (

Tai said that while speaking to Chen, he was conscious of the grave danger for the hostages while he spoke with Chen. "I knew he had a gun right there," he said. "I changed the normal manner of my questioning so I wouldn't irritate him. Also, I didn't let him know it was a live interview, because I didn't want him to have any power over me."

While Tai places responsibility for failing to control Chen's communications with the police, he said he was nevertheless shocked by the behavior of the interviewers that followed him. At one point, in the wee hours of the morning, a reporter asked Chen to sing karaoke over the radio. Another reporter angered Chen by asking flatly when he would kill himself.

While Tai does not condone such behavior, he explains it as emanating from the Taiwan media's belief in "a kind of business relationship with viewers and listeners."

For Alexander, however, neither the media nor the police are the true focal point of his story. "I think that the whole experience to us as a family was one of the reality of the grace of God," he said. "We found ourselves in a situation that by all standards we felt that we were on the point of death. We thought that we would all die, particularly when the shooting erupted ?and the fact that we were delivered from that, it was a reemphasis of the grace of God to us."

Alexander went on to point out that above and beyond his own family's experience, the book also tells of the conversion of Chen, outlining several gestures and events that he believes are responsible for the fugitive's turn toward faith. In addition to the Alexanders' praying aloud while under Chen's guns, Christine presented Chen with a drawing of a cross while captive, Alexander's wife, Anne, embraced Chen in forgiveness at the moment of his surrender, and once Chen was in jail, she and her husband visited him to present him with a Bible.

"We felt that this man who had done this to us was about as evil as you could get," said Alexander, "that there was really no hope for a man like this. But we knew as Christians that it was our duty to share the love of God with all people, including him."

During the months of incarceration before his eventual execution on Oct. 6, 1999, Chen had become a devoted Christian. He professed his newfound beliefs in several letters he wrote to the Alexanders and was also baptized in prison. For Alexander and his family, it "was an amazing lesson of just how far God would go to cater for even the vilest of people, the most evil of men, to actually bring that person to the point of salvation and to give him peace in his own soul."

Aware that much criticism and ridicule followed Chen's conversion in Taiwan, Alexander is also realistic about the turn of events. "Of course, we could be completely wrong," he said. "Perhaps he never was converted. Perhaps it was all just a game on his part ? an effort to try and manipulate. I don't know. But what we do know is that we as a family, each of us as individuals, has experienced conversion."

Now, three years later, Alexander said that his family has largely recovered from the hostage situation. "There is some lingering trauma," he said, "and there have been other changes." Shona is now married, and Melanie has moved to America. His Port Elizabeth household now consists of him, his wife, Christine and baby Zachary.

Looking back, Alexander said he is able to see some meaning in the events of Nov. 18, 1997 that he was unable to see at that time. He perhaps describes it best in the book, where he writes that in Chen's conversion, and the subsequent conversions of eight of his fellow inmates, he can now find an answer to a deep and searching question that Christine had asked him that night. Staring at the madman who promised death to her and her family, she had looked at her father and asked: "Daddy, why is this happening to us?"

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the