The WHO years ago cautioned that a mysterious “disease X” could spark an international contagion. The new coronavirus, with its ability to quickly morph from mild to deadly, is emerging as a contender.

From recent reports about the stealthy ways the COVID-19 virus spreads and maims, a picture is emerging of an enigmatic pathogen whose effects are mainly mild, but which occasionally — and unpredictably — turns deadly in the second week.

In less than three months, it has infected about 77,000 people, mostly in China, and killed more than 2,200.

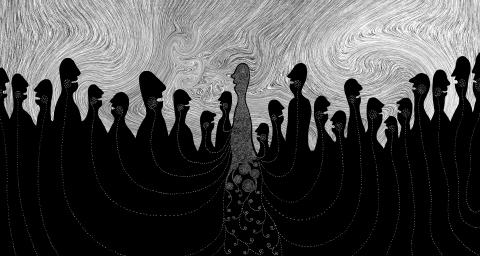

Illustration: Mountain People

“Whether it will be contained or not, this outbreak is rapidly becoming the first true pandemic challenge that fits the disease X category,” Marion Koopmans, head of viroscience at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, and a member of the WHO’s emergency committee, wrote on Wednesday last week in the journal Cell.

The disease has now spread to more than two dozen countries and territories. Some of those infected caught the virus in their local community and have no known link to China, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

“We are not seeing community spread here in the United States yet, but it’s very possible — even likely — that it may eventually happen,” CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Director Nancy Messonnier told reporters on Friday last week.

Unlike SARS, its viral cousin, the COVID-19 replicates at high concentrations in the nose and throat akin to the common cold, and appears capable of spreading from those who show no, or mild, symptoms. That makes it impossible to control using the fever-checking measures that helped stop SARS 17 years ago.

A cluster of cases within a family living in Anyang, China, is presumed to have begun when a 20-year-old woman carried the virus from Wuhan, the outbreak’s epicenter, on Jan. 10 and spread it while experiencing no illness, researchers said on Friday last week in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Five relatives subsequently developed fever and respiratory symptoms.

COVID-19 is less deadly than SARS, which had a case fatality rate of 9.5 percent, but appears more contagious. Both viruses attack the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, via which they can potentially spread.

While more than 80 percent of patients are reported to have a mild version of the disease and will recover, about one in seven develops pneumonia, difficulty breathing and other severe symptoms. About 5 percent of patients have critical illness, including respiratory failure, septic shock and multiorgan failure.

“Unlike SARS, COVID-19 infection has a broader spectrum of severity ranging from asymptomatic to mildly symptomatic to severe illness that requires mechanical ventilation,” doctors in Singapore said in a paper in the same medical journal on Thursday last week. “Clinical progression of the illness appears similar to SARS: Patients developed pneumonia around the end of the first week to the beginning of the second week of illness.”

Older adults, especially those with chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, have been found to have a higher risk of severe illness.

Still, “the experience to date in Singapore is that patients without significant co-morbid conditions can also develop severe illness,” they said.

Li Wenliang (李文亮), the 34-year-old Chinese ophthalmologist who was one of the first to warn about the coronavirus in Wuhan, died earlier this month after receiving antibodies, antivirals, antibiotics and oxygen, and having his blood pumped through an artificial lung.

The doctor, who was in good health prior to his infection, appeared to have a relatively mild case until his lungs became inflamed, leading to his death two days later, said Wang Linfa (王林發), who heads the emerging infectious disease program at Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School.

A similar pattern of inflammation noted among COVID-19 patients was observed in those who succumbed to the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, said Gregory Poland, the Mary Lowell Leary emeritus professor of medicine, infectious diseases, and molecular pharmacology and experimental therapeutics at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Whenever you have an infection, you have a battle going on,” Poland said in a telephone interview on Thursday last week. “And that battle is a battle between the damage that the virus is doing, and the damage the body can do when it tries to fight it off.”

Doctors studying a 50-year-old man who died in China last month found COVID-19 gave him mild chills and dry cough at the start, enabling him to continue working.

However, on his ninth day of illness, he was hospitalized with fatigue and shortness of breath, and treated with a barrage of germ-fighting and immune system-modulating treatments.

He died five days later with lung damage reminiscent of SARS and MERS, another coronavirus-related outbreak, doctors at the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital in Beijing said in a study in the Lancet medical journal published on Tuesday last week.

Blood tests showed an over-activation of a type of infection-fighting cell that accounted for part of the “severe immune injury” he sustained, the authors said.

Controversially, he had been given 80 milligrams twice daily of methylprednisolone, an immune-suppressing corticosteroid drug that is in common use in China for severe cases, though has been linked to “prolonged viral shedding” in earlier studies of MERS, SARS and influenza, according to the WHO.

The patient’s doctors recommended corticosteroids be considered alongside ventilator support for severely ill patients to prevent a deadly complication known as acute respiratory distress syndrome.

He was given at least double what would typically be recommended for patients with the syndrome and other respiratory indications, said Reed Siemieniuk, a general internist and a health research methodologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

Based on what was observed with MERS, the drug might delay viral clearance in COVID-19 patients, he said.

“Corticosteroids could cause more harm than good because of that risk,” Siemieniuk said in an interview. “I wouldn’t want to let a patient die without trying steroids, but I would wait until patients were extremely ill.”

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s