Detroit police have over the past two years been quietly utilizing controversial and unreliable facial recognition technology to make arrests in the city.

The news, revealed in May in a Georgetown University report, has shocked many Detroiters and sparked a public debate in the city that is still raging and mirrors similar battles playing out elsewhere in the US and across the world.

Among other issues, critics in the majority-black city point out that flawed facial recognition software misidentifies people of color and women at much higher rates.

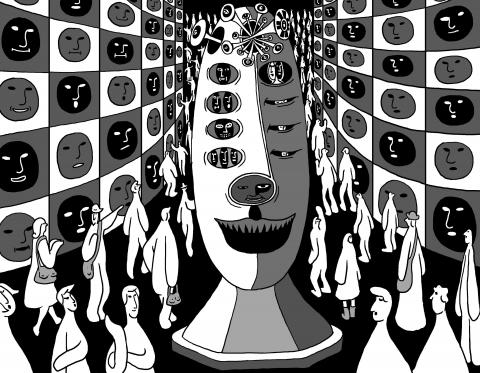

Illustration: Mountain People

Detroit also has the capability to use the technology to monitor residents in real time, although Detroit’s police chief claims that it would not.

Willie Burton, a black member of the civilian Detroit Police Commission that oversees the department, said that Detroit’s population is 83 percent black, which makes using the technology especially worrying.

“This should be the last place that police use the technology because it can’t identify one black man or woman from another,” he said. “Every black man with a beard looks alike to it. Every black man with a hoodie looks alike. This is techno-racism.”

At a July meeting on the issue held by the police commission, arguments got so heated over facial recognition that officers arrested and temporarily jailed Burton as he loudly objected to its use.

The technology presents obvious questions over whether police are violating residents’ privacy protections.

Detroit’s facial recognition software makes it much easier for the city to track people’s movements across time, while efficiently and secretly gathering personal information, said Clare Garvie, an author of the report from the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy and Technology.

“It can betray information about sensitive locations — who someone is as a person, if they’re going to church, an HIV clinic — and the [US] Supreme Court has said we have a right to privacy even if we are in public,” she said.

Garvie conservatively estimates that a quarter of the nation’s 18,000 police agencies use facial recognition technology, and that more than half of American adults’ photographs are available for investigation.

Chicago runs a similar program as that in Detroit, while the Los Angeles Police Department might be operating a small number of cameras that track the public in real time.

Some local governments are proposing regulations to limit it.

San Francisco and Oakland in California and Cambridge and Sommerville in Massachusetts have recently banned the technology. Florida’s Orlando scrapped a pilot real-time surveillance program after the software proved to be unreliable, and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo is attempting to implement facial recognition software in New York City, but without success so far.

At the federal level, the US Congress in May held hearings on the issue.

US Representative Rashida Tlaib, whose district includes parts of Detroit, has introduced legislation that would prohibit its use at public housing.

“Policing our communities has become more militarized and flawed,” Tlaib said during the May 22 hearing. “Now we have for-profit companies pushing so-called technology that has never been tested in communities of color, let alone been studied enough to conclude that it makes our communities safer.”

However, facial recognition software is just the latest in Detroit’s development of a comprehensive public surveillance apparatus that includes multiple camera programs.

As part of its Project Green Light, the city installed nearly 600 high-definition cameras at intersections, schools, churches, public parks, immigration centers, addiction treatment centers, apartment buildings, fast food restaurants and other businesses around the city.

Police pull still images from those and thousands of other private cameras, then use facial recognition software to cross-reference them with millions of photographs pulled from a mugshot database, driver’s license photographs and images culled from social media.

For example, were Detroit to start using the software in real time, it could continually scan those entering any location covered by its cameras, or motorists and pedestrians traveling through an intersection.

Although there is no oversight, Detroit Police Chief James Craig insists that the department would not use real-time software and only runs still images as an “investigative tool” for violent crimes.

Police have said that any match requires “sufficient corroboration” before an arrest can be made.

However, Garvie said that the software has led to false arrests elsewhere in the country.

Facial recognition technology’s premise “flips on its head” the idea of innocent until proven guilty, Garvie said at a recent Detroit forum on the topic.

“Biometrically identifying everyone and checking them against a watch list or their criminal history assumes they’re guilty until they prove they’re innocent by not having a record,” she said. “That’s not going to make us more secure. It’s going to make us more afraid.”

A Detroit police spokesperson could not say how many arrests had involved the technology, although Craig said that no false arrests have been made.

Craig acknowledged issues with accuracy, but stressed that matches are treated as a lead and go through a rigorous review process.

“Facial recognition is only part of methodical investigation to identify and confirm that the suspect is involved in that crime,” he said.

Some residents have said that the technology is sowing more distrust in Detroit and civil rights advocates accuse the city of intentionally muddying the waters.

Georgetown University’s report said that police did not mention on the Green Light Web site that cameras would be used with facial recognition software, and property owners who installed them were not made aware of it.

“There’s been no transparency and we won’t stand for it,” Burton said. “We don’t want it here, and we are going to fight back because we deserve better.”

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not

Deflation in China is persisting, raising growing concerns domestically and internationally. Beijing’s stimulus policies introduced in September last year have largely been short-lived in financial markets and negligible in the real economy. Recent data showing disproportionately low bank loan growth relative to the expansion of the money supply suggest the limited effectiveness of the measures. Many have urged the government to take more decisive action, particularly through fiscal expansion, to avoid a deep deflationary spiral akin to Japan’s experience in the early 1990s. While Beijing’s policy choices remain uncertain, questions abound about the possible endgame for the Chinese economy if no decisive