To get a glimpse of what is eventually to become the Lowline, a subterranean Eden being billed as the world’s first underground park, you have to swipe your MetroCard at the Lower East Side’s Delancey Street station, go down one flight of stairs, go down another, slither through a few characteristically congested subway corridors, and then up another flight, to the J train platform.

Here, in the crucible of Manhattan’s public transportation system, with its slow, industrial wheeze, is an abandoned space the size of a football field.

Seventy years ago it was the Williamsburg Bridge trolley terminal, transporting city folk between boroughs, but since 1948, it has existed in a state of dark, musty desertion, save for tall metal columns, a few men in hazmat suits and the outlines of the balloon loops in which the trolleys once turned, which are to be integrated into the park’s walkways.

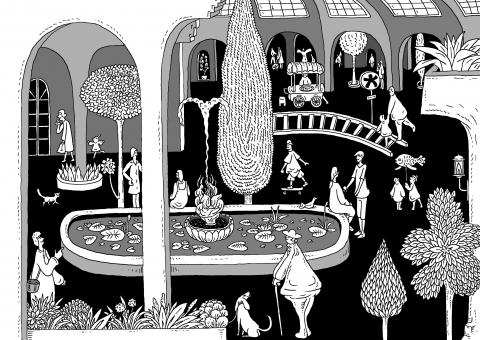

Illustration: Mountain People

Lowline cofounders Dan Barasch and James Ramsey have imagined a future for this space, one in which city dwellers take respite from the concrete jungle beneath it, thanks to remote skylight technology that filters sunlight underground through fibre-optic helio tubes.

The park, which they hope will provide one of the city’s most densely populated and aggressively gentrifying neighborhoods with more green space, is to have a ventilation system and a year-round garden.

In 2016, shortly after a pop-up called the Lowline Lab demonstrated the project’s solar redistribution technology and drew 70,000 visitors, New York City finally greenlit the Lowline, which is to cost about US$80 million to build.

“People who are trying to innovate have to be a little crazy,” said Barasch, reflecting on the 10-year anniversary of the project’s conception over coffee at the nearby members-only Ludlow House, itself a monument to the neighborhood’s rapid mega development.

“I just want to do something that has never been done before,” he said.

Ramsey, an architectural designer, got word of the abandoned space in 2009, the same year the High Line — the sleek, elevated greenway-cum-tourist attraction built on what was once a New York Central Railroad spur — opened a few kilometers north.

A friend introduced him to Barasch, who at the time was working in strategy and marketing for Google.

“Very fast I drank the Kool-Aid and believed almost wholeheartedly that technology could solve all social problems, but I still didn’t feel like I was making the world a better place,” he said of his time at the tech giant.

That year, Ramsey — a Yale-educated former NASA satellite engineer who in 2004 founded Raad design studio, which is spearheading the Lowline — brought Barasch and his entrepreneurial acumen into the fold.

When they toured the space together, they saw in its dilapidated, old-world charm an opportunity for innovation, to merge their interests in technology, architecture and New York to make the most of the city’s cosmopolitan topography. The station tower, they observed, would make for a perfect child-friendly tree house.

The initial name for the project was Delancey Underground, but the generally rapt reception to the High Line positioned Delancey as a kind of architectural antidote, both projects motivated by a desire to revive and repurpose run-down parts of the city’s transit system. Hence Lowline, which it has been called ever since.

For all its altitudinous beauty, the High Line has not escaped criticism: In the eyes of many Chelsea residents, the park has turbocharged the gentrification process, and despite nearly 5 million annual visitors, High Line cofounder Robert Hammond has rued the excess weight his team put on aesthetic considerations.

“Instead of asking [public housing tenants] what the design should look like, I wish we’d asked: ‘What can we do for you?’” he told CityLab in 2017.

Barasch, who is particularly intrigued by the reclamation of abandoned spaces and has just published a book on the subject, is hyperconscious of the paradox these endeavors pose.

The book, Ruin and Redemption in Architecture, comprises dozens of architectural case studies, divided into Lost, Forgotten, Reimagined and Transformed, and examples include the Tate Modern, Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport, Atlanta’s BeltLine and the Gemini Residence in Copenhagen.

The book also features an introductory essay by Barasch, in which the fourth-generation New Yorker remembers being charmed by the old tenement buildings near his grandmother’s Lower East Side apartment.

Yet despite his “undeniable excitement and sense of adventure” in “encountering an architectural ruin,” Barasch said that “beautiful abandoned buildings can be transformed into far less inspiring structures than their original selves.”

With the Lowline, scheduled to open in 2021, the pair hope to avoid such an outcome by blending the rough-and-tumble of old Manhattan with this new, technologically ambitious horticultural refuge.

“It’s easy to criticize things once they’re built: You can build a modern masterpiece and people will still bemoan what’s missing, the electrifying feeling of the abandoned space itself,” he said, adding that the viaduct where the High Line is was once a graffiti-strewn late-night destination for teenagers to take drugs and have sex.

“Now we have this incredibly beautiful public space that’s a huge destination for New Yorkers, but has also been referred to as a kind of corridor between glass towers, a hallway among mega developments,” Barasch said.

Residents of the Lower East Side, a historic early 20th century landing ground for European immigrants, are justifiably wary of their own neighborhood coming under siege.

Indeed, the process is already well under way: An area that was once the provenance of working-class populations and a certain grungy, New York flavor has become a hotspot for luxury residential developments, such as the one being built next to one of the neighborhood’s oldest and most quintessential attractions, Katz’s Deli.

However, Ramsey and Barasch do not see the Lowline as an addendum to the neighborhood’s propulsive modernization so much as a vehicle for community engagement.

Barasch cited the sociologist Eric Klinenberg, whose book Palaces For The People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life argues for a new “social infrastructure” or spaces, ranging from libraries and churches to community gardens and even sidewalks, that enhance civic life and human connection.

The idea is that, with renewed investment in public and private institutions of this sort, these spaces function as a kind of social scaffolding.

Barasch also said that, as much as architectural dogma suggests otherwise, good design and social responsibility do not have to be in contention with one another.

He hopes that his experience of “swimming between sectors” and Ramsey’s design bona fides will allow them to corral the funding, political support and communal goodwill to create something that is socially conscious and architecturally unprecedented.

“The Lower East Side has a very large proportion of public housing, many vulnerable residents, a very diverse population and it’s developing rapidly,” Barasch said.

“What’s needed for communities to thrive are public spheres where you attract different kinds of people. As populations grow and there’s that rising tension between affluent and low-income residents, the question becomes: What kind of equity are we providing these people when it comes to open space? What the Lowline would do is create that and also create a year-round open space, which would be first of its kind,” he said.

On a practical level, it is the prospect of green space in winter that appeals most to New Yorkers, who are constantly jostling for fresh air in a city clogged by high-rises and pure, molten commerce.

Although Manhattan is peppered with hundreds of playgrounds and community gardens, they are showing signs of age: On average they are 73 years old and were last renovated in 1997.

Moreover, a report released last year by the Center for an Urban Future estimated that the city would have to spend close to US$6 billion to bring its parks’ infrastructure up to speed.

Yet,with the city’s endorsement in 2016, the Lowline got a jolt of political goodwill, the ripple effect of which has been felt internationally; Ramsey and Barasch regularly entertain delegations from other cities, including the mayor of Paris, who spoke with them recently about her plans to build downward.

“A fresh assessment of the quality of life in our cities is long overdue,” Barasch said.

“Against the backdrop of these broader social trends, abandoned spaces take on heightened importance. I feel disappointed learning of a beautiful abandoned site being turned into a luxury condo or new retail space. It feels like the lowest common denominator, what is most likely to happen in the absence of intervention, some kind of vision for these spaces. We can’t waste what we have,” he said.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its