The former first baseman for the then-Brother Elephants, Taiwan’s equivalent of the New York Yankees, now spends most of his days and nights deep in a local stadium, in a spartan room with all the charm of an old warship.

He sleeps on a thin bed. Sports gear towers above him on metal cabinets. A coffee table overflows with snacks, ashtrays and teacups.

It is the coach’s quarters, where the former player, Tsai Feng-an (蔡豐安), directs a high-school baseball program, a shoestring operation that demands long hours and pays him a fraction of his old big-league salary. It is also where Tsai, whose name was once as famous as former Yankee first baseman Don Mattingly’s, would rather not be.

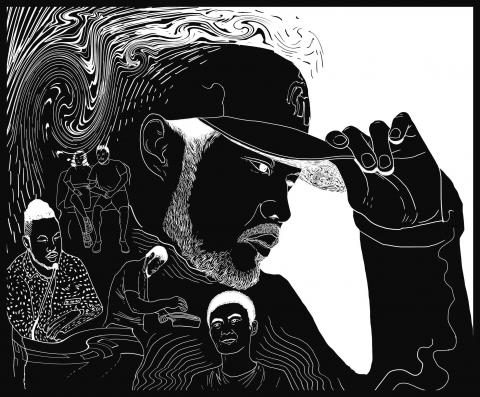

Illustration: Mountain People

“The local people are surprised that I put up with these conditions, which is why they support me, but I still look at my baseball career fondly, even though there were bad things,” Tsai said.

The bad things derive from his role in one of the biggest gambling scandals in international baseball, a scheme in which Tsai and several dozen other players in the Chinese Professional Baseball League (CPBL) were accused of throwing games from 2006 to 2009 in exchange for thousands of dollars from gamblers.

Orchestrating the fraud was a gangster who went by the nickname Windshield Wiper (雨刷), an inside joke among his associates that referred to his quick temper. It was a colorful detail in a case that was as riveting for fans and commentators as a playoff series.

Gambling in baseball is almost as old as the game itself. In the US, every fan knows about the Black Sox scandal, in which eight players threw the 1919 World Series, leading to lifetime bans. Former Cincinnati Reds Pete Rose is still barred by Major League Baseball because he bet on games.

Gambling scandals have swept through the Asian leagues with alarming regularity, exposing deep ties between crime rings and the sport even as they strive to make an international mark.

This year, several players for the Tokyo Giants, Japan’s best-known team, were accused of consorting with gamblers. However, the troubles in Taiwan were far larger. They almost sank the league.

Foreign players have thought twice before agreeing to play in Taiwan. At least one foreigner, a manager, was named in the scandal. An Australian team declined to sign a Taiwanese pitcher who was linked to the scheme, but not charged. He played in the Dodgers’ farm system this year.

The nation’s push to play host to a part of the World Baseball Classic, which is run by Major League Baseball, has slowed as well.

Before the arrest in 2009 of Windshield Wiper, whose real name is Tsai Cheng-yi (蔡政宜), the league endured several other game-fixing scandals, remarkable in a league that was founded only in 1989 and has had as few as four teams. Players were kidnapped and pistol-whipped, and their families were threatened. One coach was stabbed.

Gangsters were arrested and players banished. Attendance dipped, too, but within a year or two, many fans returned.

However, the Windshield Wiper case was much bigger.

From 2006 to 2009, Windshield Wiper and his intermediaries paid dozens of players as much as US$30,000 for each game they agreed to throw. In all, more than 40 players, coaches, retired players, gangsters and politicians were implicated, including Tsai Feng-an, Chen Chih-yuan (陳致遠) and other stars.

One manager was charged and left the country. Former Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Tainan County Council speaker Wu Chien-pao (吳健保), who ran his own gambling ring and had players beaten if they did not cooperate, was jailed. Windshield Wiper is serving a four-year sentence.

The Elephants, Tsai Feng-an’s old team, were so badly damaged, they were sold.

Attendance league-wide fell, but it perked up in 2013 when Manny Ramirez, an outfielder who had his best years with the Boston Red Sox in the early 2000s, played in Taiwan.

The CPBL has tried to head off further scandals by allowing law enforcement officials to attend every game. Players are lectured on the evils of gambling and subjected to random investigations. The criminal penalties for gambling and fraud were increased, and a national sports lottery was created to give gamblers a legal avenue to bet on games.

“We hope the worst has passed,” CPBL commissioner John Wu Chih-yang (吳志揚) said. “It’s impossible to stop Taiwanese from gambling, but we think we have good prevention now, and the influence of the mafia has decreased.”

There have been no reported cases of game-fixing since 2009, he said.

Most players involved confessed to taking part in the scheme and avoided jail by paying fines equal to the bribes they took.

They were banished from professional baseball, and having trained most of their lives to become ballplayers, they have had trouble finding work, the shame of being implicated sending them into hiding.

However, two players, Tsai Feng-an and Chen, agreed to speak to The New York Times about how they have sought to redeem themselves.

They have taken different paths.

Tsai Feng-an returned to rural Nantou County. Because of his banishment, he cannot wear a baseball uniform or coach a team, so instead he looks for money to keep his program afloat and to build a new stadium. He bunks with his coaches and players in a dingy dormitory where the communal dining area is next to a homemade indoor batting cage.

Tsai Feng-an had spent years fighting the charges that he helped throw four games. After his initial two-year jail sentence was reduced to six months, he agreed to pay a fine of about US$100,000 to settle the case. His probation, which ended in August, required that he report daily to a police station, a humiliation he found difficult after such an illustrious career.

Friends offered him jobs at a university and a technology company, where he could have earned two to three times more than the about US$1,000 a month he makes now. Instead, he returned to central Taiwan, where he grew up, to work with children and get back to basics.

“Most players would not be willing to do what I do now, teaching baseball in a school, because it’s a lot of work and not much money,” he said. “Even though I got a six-month sentence, I’m still pretty much a free soul.”

RESTAURANT OWNER

Chen lives a flashier life in Taipei. He runs a restaurant that serves Aboriginal food like fried crickets, mountain boar and betel nut flowers. His wife is a minor celebrity.

He also produces a rice snack with a friend and donates the proceeds to baseball programs in regions where poor Aboriginal children live. He tutors high-school players.

However, in Taiwan, where baseball is almost a national religion, neither man will regain the stature he commanded as a professional ballplayer. Each continues to proclaim his innocence, but the game-fixing scandal has been a hard stain to erase.

“I left baseball because of the scandals, and that’s not something that I can change, but I can change myself, set goals for myself. I have a wife and kids to take care of. I need to maintain a positive attitude,” Chen said at his restaurant, La Fung, or The Guest.

The case that was their undoing was discovered almost by accident.

A prosecutor in Banciao in then-Taipei County, Wang Cheng-hao (王正浩), received an anonymous tip after the 2008 season that hundreds of thousands of dollars were being wagered on baseball games, and Windshield Wiper was winning most of the time.

Gambling is prohibited according to the Criminal Code.

Wang and investigators looked at Windshield Wiper’s bank and telephone records and discovered a network of middlemen that ultimately led them to the players.

Windshield Wiper, who was from southern Taiwan and in his late 30s at the time, was one of the biggest gamblers in the country.

He was subtler than most gangsters. Instead of laundering money through businesses that served as fronts, he had dummy accounts set up in his friends’ names. He had no gambling convictions.

He was a baseball fan, though, and he liked to hang around ballparks, where he sat near the dugout and chatted to players, some of whom joined him for dinner. He also befriended former players living in southern Taiwan, whom he paid to recruit active players.

Wang collected evidence through the 2009 season to determine which players were involved. He made arrests when the season was over.

“If we arrested him during the season, it would have affected the games, but if we didn’t stop him after the season, it could affect more games,” Wang said in his office in Banciao.

According to court documents, one middleman, Chuang Hung-liang (莊宏亮), dealt specifically with star players, who at times received money in shoe boxes. Some players were motivated to take bribes because they were upset with their low salaries; others said they were threatened.

After his arrest, Windshield Wiper initially denied everything, but ultimately he named about 40 people. The investigation reached back four seasons, to 2006. Some of the appeals, including Tsai Feng-an’s, dragged into 2014.

A TICKET OUT

Like other players from rural Taiwan, Tsai Feng-an and Chen saw baseball as their ticket out of poverty.

Tsai Feng-an began playing in the streets with friends with whatever equipment they could find. When he was 10, he was recruited to attend a private school with a well-known team. In 1988, he was good enough to travel to the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, where his team won the title by beating the team from Pearl City, Hawaii.

When the boys returned home, they were paraded through the streets. The trip was eye-opening for the son of a bus driver and a hairdresser who rarely saw him play.

“Country folks don’t really watch baseball games,” Tsai Feng-an said over noodles at a restaurant near his school. “They have loads of things to do; they’re very busy.”

Given his modest means, playing baseball was a necessity. He turned pro in 1997 and joined the Mercuries Tigers. When that club folded after the 1999 season, he joined the Brother Elephants. He had a career year in 2002, hitting 21 home runs and batting .294. He played in the 2004 Olympics, where Taiwan finished fifth.

“By the time I became a pro, I wouldn’t say I was happy about this,” said Tsai Feng-an, rail thin and all business. “Most of the players come from poorer families, so the only thing they thought about was playing well so they would have a bargaining chip to get more money to help their families. It was a job.”

Though salaries in the CPBL have increased in recent years, they are nothing like what players in Major League Baseball earn; they are barely more than what a manager at a white-collar company might bring in.

Because they are celebrities, they are often invited to bars and restaurants, where their tabs are covered.

“Taiwanese players like to drink, and drinking is a way to relax, but once they start going out with people, that creates a lot of trouble, because people know who you are and will want a lot of things from you,” Tsai Feng-an said. “Drinking would make you do stupid things.”

Years after he had stopped playing, prosecutors accused Tsai of throwing four games.

He was sentenced in 2011 to two years in jail and ordered to pay a fine. On appeal, the sentence was reduced to a six-month term, which he avoided by paying a smaller fine.

He said that in the first few years after he left baseball, at least five groups of gangsters tried to get him to help them fix games. Some, he said, offered as much as US$300,000.

He refused.

“If I was willing to do it, I could have done it ages ago, rather than teaching kids baseball and getting 30,000 dollars a month,” he said, referring to New Taiwan dollars.

At current rates, that would be about US$950 per month.

Tsai Feng-an has three young children, but his days are spent with his players, with potential donors and at the construction site where a new county stadium is being built.

He said he gets up at 6am and finishes work at midnight.

Budgets are tight, so broken bats and worn baseballs are patched up with tape.

He said he told his students that pro ballplayers can earn a lot of money, but also spend a lot of it. Better, he said, to live modestly and humbly.

Unlike Tsai Feng-an, who works in relative anonymity, Chen lives in Taipei in plain sight. Tan and fit, he was known as the Golden Warrior for the Elephants. While once among the highest-paid players in the CPBL, earning about US$100,000 a year, Chen now tries to make ends meet.

Most days, he is at his restaurant. He advises a high-school baseball team who his brother coaches. With a friend, he produces dried snacks called hao bang (好棒), which means “good bat” in English. A cartoon of Chen’s face is on the wrappers.

The profits are spent on sports equipment for poor children, he said.

He is from an Aboriginal village in eastern Taiwan, where he said he had no refrigerator and went barefoot as a child.

The legal troubles effectively ended his career, something he has tried to get past.

Chen is now more cautious, wary of gangsters. When he is invited to dine out, he asks who else will be there. If there is a name he does not recognize, he declines the invitation.

He also tells younger players to simplify their lives, implying that he did not. After all, he was sentenced to at least a year in jail that he settled by paying a fine.

“My own story is like teaching material for other people to learn from,” he said. “The scandal is in the past and it’s bound to surface one day, so there’s no running away from it. I learned a lot, and if people don’t like it, I will do better to make them understand I’m not who they think.”

Additional reporting by Huang Shih-han

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama