Pope Francis is leading a determined push to fundamentally alter the relationship between the Vatican and China, which for decades has been infused with mutual suspicion and acrimony.

Interviews with about two dozen Catholic officials and clergy in Hong Kong, Italy and China, as well as sources with ties to the leadership in Beijing, reveal details of an agreement that would fall short of full diplomatic ties, but would address key issues at the heart of the bitter divide between the Vatican and Beijing.

A working group with members from both sides was set up in April and is discussing how to resolve a core disagreement over who has the authority to select and ordain bishops in China, several of the sources said.

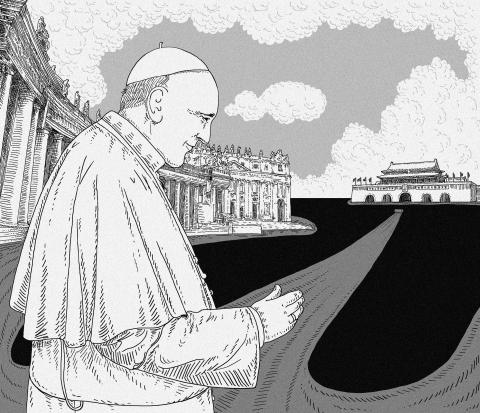

Illustration: Mountain people

The group is also trying to settle a dispute over eight bishops who were appointed by Beijing, but did not get papal approval — an act of defiance in the eyes of the Vatican.

In what would be a dramatic breakthrough, the pope is preparing to pardon the eight, possibly as early as this summer, paving the way to further detente, Catholic sources with knowledge of the deliberations said.

A signal of Francis’ deep desire for rapprochement with China came last year in the form of a behind-the-scenes effort by the Vatican to engineer the first-ever meeting between the head of the Roman Catholic Church and the leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Aides to the pope tried to arrange a meeting when both Francis and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were in New York in September last year to address the UN General Assembly.

The meeting did not happen, but the overture did not go unnoticed in Beijing.

While the two sides have said they are discussing the issue of the bishops, Catholic sources gave reporters the most detailed account yet of the negotiations and the secret steps the Vatican has taken to pave the way to a deal.

The talks come more than six decades after CCP leaders, having vanquished the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) forces of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), expelled Vatican envoy Antonio Riberi from Beijing in 1951 as they banished missionaries and began a crackdown on organized religion. The Vatican remains the only Western state that does not have diplomatic ties with Beijing, maintaining instead formal relations with Taiwan.

For the Vatican, a thaw in relations with China offers the prospect of easing the plight of Christians in China, who for decades have been persecuted by authorities. It might also ultimately pave the way to diplomatic relations, giving the Church full access to the world’s most populous nation.

An official relationship with China “would crown a dream that the Catholic Church has cultivated for many centuries: to establish a regular presence in China through stable diplomatic ties,” said Elisa Giunipero, a researcher at the Catholic University of Milan in Italy who has studied the history of the Catholic Church in China for 20 years.

For China, improved relations could burnish its international image and soften criticism of its human rights record. It would also be an important step in prizing the Vatican away from Taiwan, handing China an important diplomatic victory.

Spokespeople for the two sides acknowledged the talks are continuing, but declined to answer detailed questions about them.

“The aim of the contacts between the Holy See and Chinese representatives is not primarily that of establishing diplomatic relations, but that of facilitating the life of the church and contributing to making relations in ecclesial life normal and serene,” Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi said.

“We are willing, on the basis of the relevant principles, to continue having constructive dialogue with the Vatican side, to meet each other halfway and jointly promote the continued forward development of the process of improving bilateral ties,” the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said. “[We] hope the Vatican can likewise take a flexible and pragmatic attitude and create beneficial conditions for improving bilateral relations.”

PAPAL INVITE

Forging an agreement is unlikely to be easy. There is resistance on both sides.

Among Chinese leaders, there is concern that a deal would give the Vatican a powerful foothold in China, challenging the CCP’s absolute authority.

In the “underground” church in China, whose members have been systematically persecuted for decades by authorities, many devotees might feel betrayed by a Vatican deal with Beijing.

Catholic clergy belonging to the underground church have been detained and jailed through the years, and several bishops have died in prison, according to Catholic sources who monitor the situation in China.

The Catholic Church in China, where there are an estimated eight to 10 million devotees, is divided into two communities: the”official” church, which is represented by the state-sanctioned Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, and the “underground” church, which swears allegiance solely to the pope in Rome.

Academics estimate that the number of Christians in China belonging to all denominations might be as many as 70 million.

Despite resistance in some quarters of the Catholic Church, including in Hong Kong, Pope Francis has made improved ties with China a priority, and a tight-knit circle of envoys and advisers around the pontiff are working on a deal, multiple sources said.

After he was elected pope in March 2013, Francis sent a message to Xi congratulating him on having become president of China. Then, while flying over China in August 2014 on the way to Seoul, the pope sent his best wishes to Xi and the Chinese people. The next month, Francis sent a letter to Xi via now Argentine President Ricardo Romano, who had met the future pope when Francis was the archbishop of Buenos Aires, inviting the Chinese leader to a meeting, Romano said.

In early February, the pope sent wishes to Xi for the Lunar New Year. And on his way back to Rome from Mexico two weeks later, the pope told a news conference on the plane that he would “really love” to visit China.

NYC RENDEZVOUS

An early indication that the pope was serious about improving relations with China was his appointment in August 2013 of then Archbishop Pietro Parolin as his secretary of state, the highest ranking diplomat in the Vatican. Under Pope Benedict XVI, Francis’ predecessor, Parolin had been the Vatican’s chief negotiator with Beijing and was near to hammering out a deal with China on the appointment of bishops in 2009, people with direct knowledge of those negotiations said.

“In 2009, Parolin came very close to an agreement [with China],” said Agostino Giovagnoli, a professor of contemporary history at the Catholic University of Milan who closely follows the Vatican’s relationship with China.

Ultimately, an agreement on the bishops was not reached, as the Vatican considered it too narrow, Catholic Church sources said.

Parolin then moved to Venezuela in 2009 as the Vatican’s representative there. His departure marked the start of a period of chilly relations with China.

In June 2014, the sides restarted contacts with a meeting in Rome, according to a Catholic official.

A year later, the Vatican made its attempt to get Francis and Xi together in New York City.

The pope was scheduled to fly from New York to Philadelphia on the morning of Sept. 26 last year, departing from John F. Kennedy International Airport, his itinerary shows. Xi was heading to New York from Washington.

The airport could have provided a discreet venue for a meeting between the two leaders, away from the media glare, three Catholic officials said.

Catholic officials and clergy, and sources in China with knowledge of the contacts, offer differing accounts of why the leaders ultimately did not meet, but all agree that the pope wanted to meet Xi and that this message was communicated clearly to China.

According to a Chinese source with direct knowledge of the matter, Beijing “could not make up its mind whether it should take place before or after the signing of an agreement.”

In October last year, a six-person Vatican delegation made a visit to Beijing, followed by another meeting in January.

A breakthrough came in April when the sides agreed to set up a working group, two Catholic Church officials said.

The group is modeled on the Joint Liaison Group that Britain and China adopted to iron out issues before the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997, one of the officials said.

The pope, one Catholic official said, has given “clear instructions to continue the dialogue [with China] and find a resolution.”

The working group, which met in May, has been charged with hammering out technical solutions to the dispute over the ordination of bishops in China.

It is currently discussing how to resolve the issue of eight bishops who were ordained in China without papal consent, according to Church officials and other Catholic sources with knowledge of the deliberations.

Going forward, the Holy See wants to prevent a situation in which bishops are appointed by an authority other than the pope.

EXCOMMUNICATED BISHOPS

Catholic officials said there are 110 bishops in China, most of whom have been sanctioned by the CCP. There are about 30 bishops who are part of the underground church and have pledged allegiance only to the pope.

Most of the bishops recognized by Beijing have also sought the pope’s blessing and received it, but there are eight bishops who were ordained in China and do not have papal approval. They are considered illegitimate by the Vatican.

Three bishops in this group of eight have been officially excommunicated by the Vatican, according to public statements issued by the Holy See. The other five were told through informal channels that the pope opposed their ordination as bishops, Catholic sources said.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that at least two of the eight bishops reportedly have children or girlfriends, two Catholic sources said.

That is a direct affront to the celibacy pledge taken by Catholic priests.

Reporters were unable to independently confirm the personal status of these bishops.

Catholic Church officials and Catholic clergy with knowledge of the discussions said that the pope is preparing to pardon these eight bishops. The papal pardon would coincide with the Jubilee of Mercy, a year in which Catholics are urged to seek forgiveness for their offenses and forgive those who have offended them.

GOODWILL GESTURE

The Vatican hopes a pardon would be interpreted by China as a goodwill gesture.

“I believe Pope Francis wishes to use the occasion of the Holy Year of Mercy to force a breakthrough,” said Father Jeroom Heyndrickx, a Belgian missionary and member of the Vatican Commission for the Church in China, which was set up under Pope Benedict to advise the Holy See on relations with China.

The jubilee year ends in November.

The eight bishops whom the Vatican considers illegitimate can be readmitted to the Catholic Church if they receive a papal pardon.

By the end of last month, two out of the eight had not yet sent Francis a clear request for pardon, Catholic Church officials said.

Since the Vatican does not consider these eight bishops fit to run a diocese, the two sides are discussing a possible compromise that would allow them to retain their titles, but be assigned to other tasks, Catholic officials said.

Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association foreign affairs office director Chen Jianming said it would be difficult to arrange interviews with any of its bishops.

“They’re very busy people, often out in the field. Interviews would be very difficult,” Chen said.

The Patriotic Association and the State Administration for Religious Affairs in Beijing did not respond to questions about the negotiations with the Vatican.

The joint working group is also discussing another vexing issue — a mechanism whereby new bishops will be selected. The sides have failed to resolve this matter in nearly 30 years of on-and-off contact. Attempts to find a solution under popes Benedict and John Paul II failed.

In line with centuries of Catholic tradition, bishops are appointed by the pope, but China adopts a model whereby bishops are chosen by the local Chinese clergy, who are members of the CCP-controled Patriotic Association.

Under a solution being discussed, the bishops would be selected by the clergy in China. The pope would have the power to veto candidates he considers unfit, but the Vatican would need to provide evidence that the person in question is unqualified for the position, according to Catholic Church officials and clergy.

A key concern for Rome is that priests in China could face pressure or be offered inducements to favor candidates.

A source in Beijing with ties to the leadership said the sides have reached a tentative agreement on the future appointment of bishops, but did not provide details.

If a deal can be forged on the selection of new bishops, the Vatican then hopes to focus on an agreement that would see Beijing recognize the bishops who are members of the underground church.

A sudden reversal last month by a high-profile Chinese bishop underscores the sensitivity of this issue. Auxiliary bishop of Shanghai Thaddeus Ma Daqin (馬達欽) angered Beijing when he announced that he could not remain in the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association at his ordination ceremony in 2012, but Ma, who has since been under house arrest at the Sheshan mountain seminary on the outskirts of Shanghai, wrote in a June 12 blog that in retrospect, the move had been “unwise.”

It is unclear why Ma recanted, but some Catholic officials are concerned that the bishop was pressured into making the statement by Chinese authorities.

That could be interpreted as an affront to the pope, one Catholic official said.

Other Catholic sources speculated that Ma might have acted voluntarily in an effort to defuse his confrontation with Beijing and help smooth the way to a deal.

Chinese authorities did not reply to questions about Ma’s decision.

FOREIGN INFLUENCE

In his effort to forge a breakthrough with China, Francis will have to overcome deep-seated fears.

China views the Church with suspicion, a source in Beijing with ties to the Chinese leadership said.

For the CCP, which is officially atheist, but recognizes five religions, the existence of a religion that recognizes a foreign leader as its moral authority is viewed as a potential threat.

CCP leaders, who were traumatized by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, are acutely aware of the role played by the Catholic Church in the fall of communist regimes, such as the 1989 revolution in Poland, the homeland of the late John Paul II.

Within China there are also competing forces that could trip up an agreement, Chinese and Catholic officials said.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs views detente with the Holy See as a way to isolate Taiwan, as the Vatican would likely have to sever ties to Taipei in the event of full diplomatic relations with Beijing, but the United Front Work Department, a party body whose mission is to spread China’s influence, is less enthusiastic, fearing the threat of foreign religious infiltration.

“Internally, there is division over whether the pope can be trusted or not,” a source with leadership ties said.

For centuries, the Catholic Church has struggled to make inroads in China, where foreign influence, including Christianity, has been met with suspicion. That distrust erupted at the turn of the 20th century with the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion, which targeted foreigners, including Christian missionaries, as well as Chinese Christians.

However, relations have not always been fraught. Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit like Pope Francis who arrived in the country in the late 16th century, embraced Chinese culture and became fluent in Mandarin, earning him access to the court of Ming dynasty Emperor Wanli (萬曆). Ricci, who died in 1610, was buried in Beijing with the approval of the emperor.

In some quarters of the church, there are varying degrees of opposition to a deal with China. While Parolin is spearheading the drive for an agreement, the Vatican department in charge of foreign missionary work is more cautious about a deal, Catholic sources said.

’FOLLOW THE POPE’

Criticism is especially strong in Hong Kong which, along with Macau, has long served as a beachhead for Catholicism in China. The former British colony is home to missions and clergy that maintain extensive networks among both foreign and Chinese priests working in China, many underground.

The most outspoken opponent is Cardinal Joseph Zen (陳日君), a former bishop of Hong Kong, who is a member of the Commission for the Catholic Church in China, the advisory body set up by Benedict.

Some members of the commission opposed the draft deal the Vatican hammered out with China in 2009, several people with knowledge of the deliberations said.

“The Chinese government has no intention to give in on anything,” said Zen, a respected figure in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement.

Under Francis, the commission has been sidelined. While it has not been dismantled, the body has not convened since he became pope. And the talks with China are being led by Rome-based Vatican officials.

“Chinese Catholics want to be reunited in a single church, but it is difficult to think of a deal that could satisfy everyone,” said a Chinese bishop who was appointed by Beijing and is also recognized by the pope.

Some members of the underground church, who spoke to reporters on condition of anonymity, are especially dubious about a deal with China. Many have faced harsh persecution.

Catholic clergy are closely watched by Chinese security forces, and priests have been pressured to register with the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, Catholic sources said.

China Aid, a Texas-based group that monitors the Chinese government’s treatment of all Christian denominations in China, said in its annual report this year that repression by the state had escalated.

In areas where state repression was particularly strong, it pointed to the forcible closure of secretive house churches, the detention of “large numbers of pastors, church leaders and Christians,” and the confiscation of church property.

The Chinese foreign ministry did not respond to questions about religious persecution.

Bishops in the underground church have been jailed and subjected to forced labor, according to reports in Catholic media.

Shi Enxiang (石恩翔), the underground bishop of Yixian, died last year after having been detained in 2001, according to UCANews, a Catholic news service focused on Asia.

The bishop, who was 94, had been confined to prison or labor camps for about half his life, UCANews said.

“A full reconciliation needs time. If you go too fast, some segments of the underground church could feel betrayed,” said Antonio Sergianni, a former Vatican official who worked on the China desk in Rome for 10 years until 2013.

However, “if the pope shows a new path, we need to follow the pope,” he said.

Additional reporting by Philip Pullella, Ben Blanchard and Hugh Bronstein

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural