In Kampala, driving is not just something you do to get from A to B. It is a battle of egos and wit. Who will chicken out first from a possible collision?

It is a battle Uganda’s drivers take very seriously, particularly during rush hour. Even if you win a battle, and you manage to bully another car off the road, it is likely that the car that was bullied will seek revenge — hooting, screeching past and then suddenly breaking right in front of you, the driver with a satisfied smirk on his face. And it is usually a man.

Oh yes, there is a lot of sexism on Uganda’s roads. When a woman makes a mistake, or even if her car has simply broken down, most people will pass by and sneer: “Of course it is a woman.”

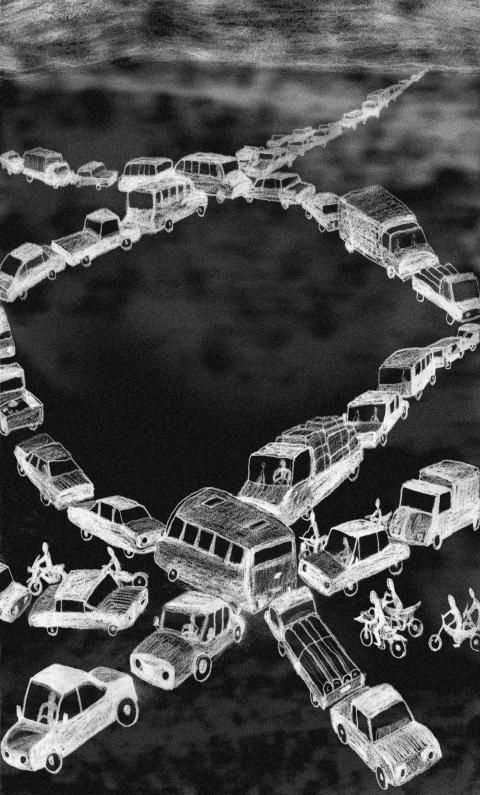

Illustration: Mountain People

If it is a man making the traffic worse, people will glance at him sympathetically or even nonchalantly. He is a man. It must have been a problem beyond his control.

In this unholy mess, where, in a car, you can be stuck in traffic for an hour, the boda boda, a motorcycle taxi, is your one savior. As you sit on one, trying to clutch your purse so it is not grabbed along the way while at the same time holding on to cold metal or a strange man for dear life, it is hard to decide whether they are a blessing, curse or exotic experience.

Often unregulated, and immune to traffic rules, motorcycle taxis in Kampala contribute to Uganda’s high road accident fatality rates — one of the highest in the world.

However, it is not just accidents that are causing deaths. An unreliable public transport system has pushed almost everyone who can afford a car to buy one, and the pollution is alarming.

The cars are mostly Japanese made, used there for years — even decades — before being discarded to Uganda. The fumes from hundreds of cars on roads that were never meant for so much traffic mix with the stench from open sewers.

Most people in Kampala have accepted rush hour travel in the city, knowing that a failed transport system and the pollution that comes with it are signs of the bigger African problem of development.

A minibus belches black smoke; the truck behind it in the traffic jam billows white fumes. Eyes smart in the smog, as diesel gases from thousands of 10 and 15-year-old vehicles fill Nairobi’s hazy evening air.

This jam could last for one, three, even five hours — last year, one stretched for 50km — all the while adding to pollution levels that are “beyond imagination,” a resident said.

It could easily be Cairo, Lagos or another African megacity, but this is the eight-lane Mombasa Road in Kenya’s capital — a permanently clogged artery in a metropolis where the number of vehicles doubles every six years.

Kenya is one of the few countries in Africa to have banned cars using the most sulfurous fuels, but research there suggests this is still one of the most polluted cities in the world — made worse by smoke from roadside rubbish fires, diesel generators and indoor cooking stoves.

However, no one knows for sure, because like nearly all African cities, Nairobi does not regularly monitor its urban air quality.

“In 28 years of living in Nairobi, I have seen the number of people quadruple and car ownership go from 5 percent to 27 percent. The pollution is mind-boggling,” said Dorothy McCormick, a Nairobi University economics researcher and author on African transport.

“Black grit collects on cars over a weekend, clothes get filthy and there is dust everywhere. There are 16 times as many vehicles on the road as when I came; the city just cannot cope,” McCormick said.

With half the world’s population growth over the next 30 years expected to occur in Africa, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) expects the number of cars in African cities to rise dramatically.

“The vehicle fleet will double in the next seven years in Nairobi,” said Rob de Jong, head of UNEP’s urban environment unit. “The number of cars in Africa is still relatively small, but the emissions per vehicle are much higher [than the rest of the world].”

Africa’s urban air is especially bad, because so few cars are new, the majority having been shipped in secondhand from Japan and Europe with their catalytic converters and air filters dismantled. It is in danger of becoming a dumping ground for the world’s old cars — importing vehicles that no longer meet pollution standards.

Across the continent, this explosion in car numbers, coupled with people cooking indoors on wood-fired stoves, is creating an urban health crisis already estimated by the UN to be killing 776,000 people a year. If unchecked, within a generation it will kill twice as many each year, with devastating costs to public services and economies.

“Africa is urbanizing and ‘motorizing’ faster than any other region in the world,” De Jong said. “Its pollution is not yet level with New Delhi or Beijing, but it is getting there quickly. Respiratory diseases are now the number one disease in Kenya and that is directly linked to air pollution. It is rapidly on the rise.”

According to Marie Thynell, an urban researcher at Sweden’s Gothenburg University who led a study of Nairobi pollution last year: “The amount of cancer-causing elements in the air within the city is 10 times higher than the threshold recommended by the WHO.”

Thynell’s research uncovered dramatically high pollution spikes on all of Nairobi’s main roads.

“The pollution is uncontrolled and particularly deadly in slum districts and for drivers, street vendors and traffic police,” she said.

Michael Gatari, an environmental scientist at the Kenyan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology, predicts the nation will have “a very sick population in years to come. Even what limited data there is suggests [air pollution] is around 30 times worse than in London, and that Kenya is building up an immense health problem.”

“Thirty percent more diesel is being burned in Nairobi compared with five years ago. Without doubt, the pollution will have a huge economic and health impact. We will see more and more cancers and heart disease, many more asthma cases and respiratory diseases,” he said.

African air pollution is closely linked to poverty, Gatari said.

“In the slums, people light an open fire and close their windows; they are enclosed in very high pollution. Drivers mix good diesel with kerosene. There is a lot of burning of plastics and no proper incineration. Dust is blown everywhere by the wind, and there is loose soil from farming,” he said.

In west Africa, the manmade air pollution from the string of coastal cities, including Lagos, Accra, Abidjan and Cotonou, is now so bad that it is mixing with natural pollutants blown from the Sahara and affecting cloud cover and the rain, said Mat Evans, professor of atmospheric chemistry at York University, who is leading a large-scale investigation of air pollution in the region.

“A chain of megacities is building in Africa,” he said. “The continent is in the same position that China was 20 years ago. If Africa does not regulate its air pollution, it will be a disaster.”

The WHO highlighted the danger from air pollution last month when it released data on 3,000 cities worldwide. The few African cities that had public monitoring records all had particulate matter (PM) levels way above UN guidelines, and four Nigerian cities were among the world’s 20 worst-ranked.

Onitsha, a commercial hub in eastern Nigeria, had the world’s worst official air quality. A roadside monitor there registered 594 microns/m3 of one type of particulate matter, PM10s, and 66 of the more deadly PM2.5s — nearly twice as bad as notoriously polluted cities such as Kabul, Beijing and Tehran, and 30 times worse than London.

Evans says that African cities have different problems from London, where “pollution is mainly due to the burning of hydrocarbons for transport that can be addressed by tackling fuel usage through electric vehicles and car-free zones.”

African pollution is not like that, he said.

“There is the burning of rubbish, cooking with inefficient solid fuel stoves, millions of small diesel electricity generators, cars which have had their catalytic converters removed and petrochemical plants, all pushing pollutants into the air over the cities. Compounds such as sulfur dioxide, benzene and carbon monoxide that have not been a problem in Western cities for decades may be a significant problem in African cities. We simply don’t know,” he said.

One important step forward would be to stop the dumping of old cars in Africa, De Jong said.

“If African countries could set an age limit on imports, they could quickly improve pollution, and leapfrog technologies. The majority of vehicles which will be on the road in Africa in 10 years’ time are not here yet. If these countries impose higher import standards, the majority of the fleet will soon be compliant, but if we wait nine years, the majority of cars will have come to Africa and it will be locked into heavy pollution,” he said.

De Jong advocates the widespread use of electric bikes.

“In China there will be 300 million by 2020. They are cheaper than petrol. It’s purely a policy and awareness problem,” he said. “The problem can be avoided by acting now. There is a massive opportunity for Africa to go down another road. Its air pollution must be a priority for the world.”

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into