Ever since her elderly neighbor moved a decade ago, Yoriko Haneda has done what she could to keep the empty house she left behind from becoming an eyesore. Haneda regularly trims its shrubs and clips its narrow strip of grass, maintaining its perfect view of the sea.

However, the volunteer yard work has not extended to the house two doors down. That one is vacant too, and overgrown with bamboo. In fact, dozens of houses in the hillside neighborhood about an hour’s drive from Tokyo are abandoned.

“There are empty houses everywhere, places where nobody has lived for 20 years, and more are cropping up all the time,” said Haneda, 77, complaining that thieves had broken into her neighbor’s house twice and that a typhoon had damaged the roof of the one next to it.

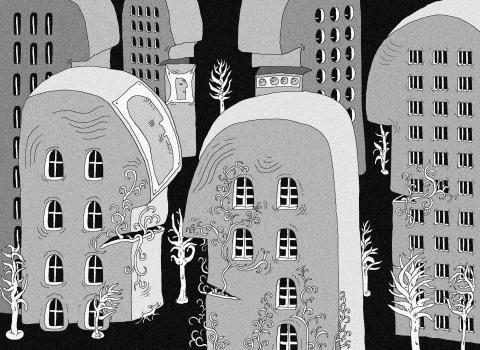

Illustration: Mountain People

Despite a deeply rooted national aversion to waste, discarded homes are spreading across Japan like a blight in a garden. Long-term vacancy rates have climbed significantly higher than in the US or Europe, and about 8 million dwellings are now unoccupied, according to a Japanese government count. Nearly half of them have been forsaken completely — neither for sale nor for rent, they simply sit there, in varying states of disrepair.

These ghost homes are the most visible sign of human retreat in a nation where the population peaked a half-decade ago and is forecast to fall by a third over the next 50 years. The demographic pressure has weighed on the Japanese economy, as a smaller workforce struggles to support a growing proportion of elderly people, and has prompted intense debate over long-term proposals to boost immigration or encourage women to have more children.

For now, though, after decades during which it struggled with overcrowding, Japan is confronting the opposite problem: When a society shrinks, what should be done with the buildings it no longer needs?

LACK OF BUYERS

Many of Japan’s vacant houses have been inherited by people who have no use for them and yet are unable to sell because of a shortage of interested buyers. However, demolishing them involves tactful questions about property rights, and about who should pay the costs. The government passed a law this year to promote demolition of the most dilapidated homes, but experts say the tide of newly emptied ones will be hard to stop.

“Tokyo could end up being surrounded by Detroits,” said Tomohiko Makino, a real-estate expert who has studied the vacant-house phenomenon. Once limited mostly to remote rural communities, it is now spreading through regional cities and the suburbs of major metropolises. Even in the bustling capital, the ratio of unoccupied houses is rising.

Yokosuka is on the front lines. Within commuting distance of Tokyo, and close to naval bases and automobile factories, it attracted thousands of young job seekers in the era of roaring economic growth that followed World War II. Land was scarce and expensive, so the newcomers built small, simple homes wherever they could.

Today the boom is relentlessly reversing itself. The young workers of the post-war years are now retirees and few people, their children included, want to take over their homes.

“Their kids are in modern high-rises in central Tokyo,” Makino said. “To them, the family home is a burden, not an asset.”

Japan’s birthrate has been stuck below the level needed to maintain the population since the 1970s, as young people postpone marriage and many women put off having children as they enter the workforce.

The city of Yokosuka is trying to change that, by encouraging owners of abandoned houses to tidy them up and put them on the market. It has established an online “vacant home bank” to showcase houses that commercial real-estate agents will not touch. Land prices in Yokosuka are down by 70 percent since their peak at the end of the 1980s.

The houses are a steal for the rare souls who will have them. Just one has been sold through the home bank so far, a 60-year-old single-story wooden home with a patch of garden that was listed for ¥660,000 (US$5,400). Places farther up the hill can be had for the equivalent of just a few hundred dollars. Four have been rented, including one to students in a nursing-care program at a nearby college who receive a discount in return for checking up on elderly people in the area.

INCENTIVES

Other towns have tried their own creative solutions, including offering cash payments to outsiders who move in and buy unoccupied homes. A few have succeeded in attracting pockets of artists and freelance workers, who stay tethered by the Internet to their urban clients.

There is even a sprawling art project, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, which has taken unoccupied buildings in a cluster of towns northwest of Tokyo and turned them into contemporary artworks. Visitors can spend the night in Dream House designed by performance artist Marina Abramovic, with coffin-like beds and tinted lights designed to elicit dreams, or tour other buildings that have been intricately carved, painted or filled with sculptural installations.

“They may not be used for their original purpose anymore, but preserving them physically is important,” project founder Fram Kitagawa said. “The key is to preserve them in a positive way.”

However, raw numbers suggest there is a limit to how many homes can be rescued through reuse. Japan’s population of 127 million is expected to drop by a million per year in the coming decades. Efforts to increase its low birthrate have been only modestly successful, and the public has shown no appetite for mass immigration.

“We have too much infrastructure,” said Takashi Onishi, an urban planning professor and the president of the Science Council of Japan.

The government, he believes, will eventually have to cut services like water and road and bridge maintenance in the most depopulated areas.

“We can’t maintain it all. We’ll have to make those hard choices,” he said.

The most blunt solution for abandoned houses is to tear them down, before they become hazards or their neighborhoods earn an irreversible reputation for blight. However, owners can be hard to track down, and are often reluctant to pay demolition costs.

The house that Haneda tends is owned by the family of Mioko Utagawa, 74, who lives a 10-minute walk down the hill. Utagawa’s husband bought it for an aunt in the 1970s after she divorced and moved there from Tokyo. Now she is in a nursing home. The family has been paying her modest property taxes, but has otherwise left the house alone. The interior is a musty wreck; a small addition that once housed the bath has been ripped out, and the bathtub sits upturned on the faithfully manicured lawn.

“Even if we fixed it up nobody would want it,” Utagawa said.

DEMOLITION

The Utagawas agreed to have the house demolished, after the city offered to subsidize the estimated ¥3 million cost, under a municipal program introduced last year to deal with hazardous or hopelessly unsellable homes. It is scheduled for destruction this fall.

Noriyuki Shima, the director of the city’s planning department, said cost considerations meant the city was targeting only the worst-affected neighborhoods.

“Giving public money to demolish a private house is not something we can do lightly,” he said.

The new national law, which came into effect in May, could help more municipalities cull their vacant houses. Among other changes, it removed a perverse incentive that has contributed to the problem. A tax break introduced decades ago to encourage home construction sets property tax rates on vacant lots at six times the level of those on built-up land. That means that if an owner demolishes a home, the tax rate soars — a big reason many let even crumbling houses stand.

Now the government can revoke the preferential tax treatment for houses whose absentee owners are letting them fall apart. However, some critics say Japan needs a more fundamental shift in its approach to housing, which has long prioritized new construction over reuse.

Hidetaka Yoneyama, a housing specialist at think tank Fujitsu Research Institute, says that until recently, homes in Japan were built to last only about 30 years, when they were then expected to be torn down and rebuilt. Building quality is improving, but the market for second-hand homes remains tiny. Developers are still building more than 800,000 new homes and condominiums a year, despite the glut of vacancies.

“In the high-growth era, everyone was happy with this arrangement,” Yoneyama said.

However, he calculates that in 20 years, more than one-quarter of Japanese houses could be empty.

“Now the tables are turned. The population is declining and no one wants to live in these old houses,” he said.

Additional reporting by Hisako Ueno

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s

In an eloquently written piece published on Sunday, French-Taiwanese education and policy consultant Ninon Godefroy presents an interesting take on the Taiwanese character, as viewed from the eyes of an — at least partial — outsider. She muses that the non-assuming and quiet efficiency of a particularly Taiwanese approach to life and work is behind the global success stories of two very different Taiwanese institutions: Din Tai Fung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC). Godefroy said that it is this “humble” approach that endears the nation to visitors, over and above any big ticket attractions that other countries may have