On the day she left for Syria, Sahra strode along the train platform with two bulky schoolbags slung over her shoulder. In a grainy image caught on a security camera, the French teenager tucks her hair into a headscarf.

Just two months earlier and a two-hour drive away, Nora, also a teenage girl, had embarked on a similar journey in similar clothes. Her brother later learned she had been leaving the house every day in jeans and a pullover, then changing into a full-body veil.

Neither had ever set foot on an airplane. Yet both journeys were planned with the precision of a seasoned traveler and expert in deception, from Sahra’s ticket for the March 11 Marseille to Istanbul, Turkey, flight to Nora’s secret Facebook account and overnight crash pad in Paris.

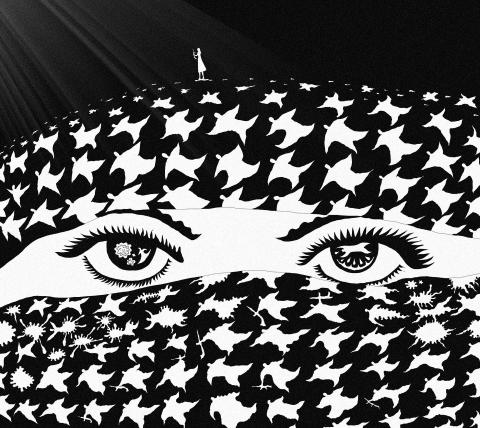

Illustration: Mountain People

Sahra Ali Mehenni and Nora El-Bahty are among about 100 girls and young women from France who have left to join the jihad in Syria, up from just a handful 18 months ago, when the trip was not even on Europe’s security radar, officials say.

They come from all walks of life — first and second generation immigrants from Muslim countries, white French backgrounds, even a Jewish girl, according to a security official who spoke anonymously because rules forbid him to discuss open investigations.

These departures are less the whims of adolescents and more the highly organized conclusions of months of legwork by networks that specifically target young people in search of an identity, according to families, lawyers and security officials.

These mostly online networks recruit girls to serve as wives, babysitters and housekeepers for jihadis, with the aim of planting multi-generational roots for an Islamic caliphate.

Girls are also coming from elsewhere in Europe, including between 20 and 50 from Britain. However, the recruitment networks are particularly developed in France, which has long had a troubled relationship with its Muslim community, the largest in Europe. Distraught families plead that their girls are kidnap victims, but a proposed French law would treat them as terrorists liable to be arrested upon their return.

Sahra’s family has talked to her three times since she left, but her mother, Severine, thinks her communication is scripted by jihadis, possibly from the Islamic State, formerly known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

“They are being held against their will,” said Severine, a French woman of European descent. “They are over there. They’re forced to say things.”

The Ali Mehenni family lives in a red-tiled middle-class home in Lezignan-Corbieres, a small town in the south of France. Sahra, who turns 18 on Saturday, swooned over her baby brother and shared a room with her younger sister. However, family relations turned testy when she demanded to wear the full Islamic veil, dropped out of school for six months and closed herself in her room with a computer.

She was in a new school and she seemed to be maturing — she asked her mother to help her get a passport because she wanted her paperwork as an adult in order.

On the morning of March 11, Sahra casually told her father she was taking extra clothing to school to teach her friends to wear the veil.

Kamel stifled his anxiety and drove her to the train station. He planned to meet her there just before dinner, as he did every night.

At lunchtime, she called her mother.

“I am eating with friends,” she said.

Surveillance video footage showed at that moment, Sahra was at the airport in Marseille, preparing to board an Istanbul-bound flight. She made one more telephone call that day, from the plane, to a Turkish number, her mother said.

By nightfall, she had not returned. Her worried parents went to the police. They noticed the missing passport the next day.

“Everything was calculated. They did everything so that she could plan to the smallest detail,” Severine said. “I never heard her talk about Syria, jihad. It was as though the sky fell on us.”

Sahra told her brother in a brief call from Syria that she had married a 25-year-old Tunisian she had just met, and her Algerian-born father had no say because he was not a real Muslim.

Her family has spoken to her twice since then, always guardedly, and communicated a bit on Facebook. However, her parents no longer know if she is the one posting the messages.

Sahra told her brother she is doing the same things in Syria that she did at home — housework, taking care of children. She says she does not plan to return to France and wants her mother to accept her religion, her choice, her new husband.

Nora’s family knows less about her quiet path out of France, but considerably more about the network that arranged her one-way trip to Syria.

Nora grew up the third of six children in the El-Bahty family, the daughter of Moroccan immigrants in the tourist city of Avignon. Her parents are practicing Muslims, but the family does not consider itself strictly religious.

She was recruited on Facebook. Her family does not know exactly how, but propaganda videos making the rounds play to the ideals and fantasies of teenage girls, showing veiled women firing machine guns and Syrian children killed in warfare. The French-language videos also refer repeatedly to France’s decision to restrict the use of veils and headscarves, a sore point among many Muslims.

Nora was 15 when she departed for school on Jan. 23 and never came back.

The next day, Foad, her older brother, learned that she had been veiling herself on her way to school, that she had a second telephone number and that she had a second Facebook account targeted by recruiters.

“As soon as I saw this second Facebook account I said: ‘She’s gone to Syria,’” Foad said.

The family found out through the judicial investigation about the blur of travel that took her there. First she rode on a high-speed train to Paris. Then she flew to Istanbul and a Turkish border town on a ticket booked by a French travel agency, no questions asked.

A young mother paid for everything, gave her a place to stay overnight in Paris and promised to travel with her the next day, according to police documents. She never did.

Nora’s destination was ultimately a “foreigners’ brigade” for the Nusra Front in Syria, Foad said. The idea apparently was to marry her off. However, she objected and one of the emirs intervened on her behalf. For now at least, she remains single, babysitting children of jihadis. She has said she wants to come home and Foad traveled to Syria, but was not allowed to leave with her.

“As soon as they manage to snare a girl, they do everything they can to keep her,” Foad said. “Girls aren’t there for combat, just for marriage and children. A reproduction machine.”

Two people have been charged in Nora’s case, including the young mother. Other jihadi networks targeting girls have since been broken up, including one where investigators found a 13-year-old girl being prepared to go to Syria, according to a French security official.

“It is not at random that these girls are leaving. They are being guided. She was being commanded by remote control, and now she has made a trip to the pit of hell,” family lawyer Guy Guenoun said.

Additional reporting by Gregory Katz

You wish every Taiwanese spoke English like I do. I was not born an anglophone, yet I am paid to write and speak in English. It is my working language and my primary idiom in private. I am more than bilingual: I think in English; it is my language now. Can you guess how many native English speakers I had as teachers in my entire life? Zero. I only lived in an English-speaking country, Australia, in my 30s, and it was because I was already fluent that I was able to live and pursue a career. English became my main language during adulthood

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act