Since Britain handed back colonial Hong Kong in 1997, retired primary school teacher and Falun Gong devotee Lau Wai-hing (劉慧卿) has fully exercised the freedoms China promised this territory of 7.2 million.

Lau and fellow believers regularly staged protests to explain the teachings of their spiritual movement and draw attention to the persecution of followers on the mainland, where the sect is banned. Until about a year ago, their protests were uneventful. That changed when a noisy rival group set up their placards and banners on the same pavement in the busy shopping area of Causeway Bay.

The 63-year-old Lau and her fellow protesters said they have been punched, shoved and sworn at since the newcomers from the “Care for the Youth Group Association Hong Kong” arrived with their blaring loudspeakers. Each protest is now a battle to be heard.

“It is much more difficult now, given these attacks, this external pressure, these forces from China,” Lau said amid the amplified din on Sogo Corner, Hong Kong’s neon-lit version of New York’s Times Square.

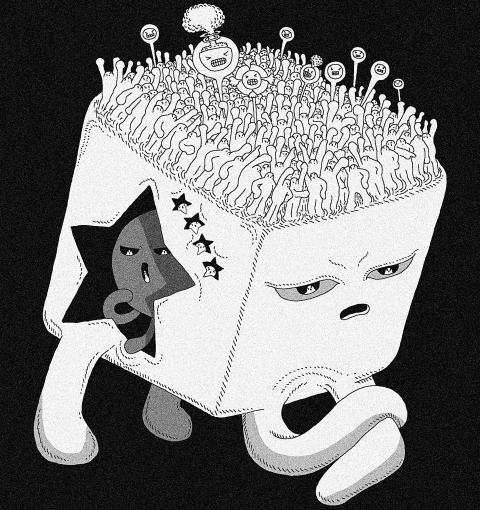

For critics of the pro-Beijing government in Hong Kong, groups like the Care for the Youth Group Association are part of a campaign from the mainland to tighten control over China’s most freewheeling territory. Increasingly, they say, Beijing is raising its voice. In the streets, boardrooms, newsrooms, churches and local government offices, individuals and organizations with links to the state and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are playing a bigger role in civil and political life, well-placed sources in Hong Kong and Beijing say.

Whenever there are antigovernment public protests, a pro-Beijing counter movement invariably appears. This year’s 25th anniversary commemoration of the protests centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square drew a rival demonstration to defend China’s bloody crackdown on June 4, 1989.

Mainland officials based in Hong Kong now routinely seek to influence local media coverage.

Catholic priests in Hong Kong say that agents from China’s security service have stepped up their monitoring of prominent clergy.

And, Beijing’s official representative body, the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong, now is able to shape policy in the office of Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying (梁振英), say two sources close to the territory’s leader.

Residents of this global financial center could not help noticing a more overt sign of China’s rule in the former British colony: Huge Chinese characters spelling out “People’s Liberation Army” in a blaze of neon alongside the military’s waterfront headquarters that suddenly appeared at the beginning of last month.

For Beijing’s critics in Hong Kong, the 1997 handover is feeling more like a takeover.

“Blatant interference is increasing,” says Anson Chan (陳方安生), who led Hong Kong’s 160,000-strong civil service in the last years of British rule and continued in that role for several years after the handover.

Chan cited as examples pressures on Hong Kong companies not to advertise in pro-democratic newspapers, attempts to limit debate about democratic reform and the higher profile increasingly being taken by Beijing’s official representatives in the territory.

“It’s not another Chinese city and it shouldn’t become one. Hong Kong is unique,” Chan said.

TOUGHER LINE

In China’s opaque political system, it is impossible to determine whether the party’s growing clout in the territory is entirely the result of a campaign organized from on high, or partly the doing of mainland and local officials eager to please Beijing. Still, a tougher line on Hong Kong is coming from the top.

Despite promises that post-handover Hong Kong should enjoy a high degree of autonomy, Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平), is said to have decided that Beijing has been too lenient.

“Xi Jinping has rectified [China’s] policy for governing Hong Kong,” a source close to the Chinese leader told reporters in Beijing, requesting anonymity. “In the past, the mainland compromised toward Hong Kong too much and was perceived to be weak.”

This tightening grip has fueled resentment and sparked a civil disobedience movement called “Occupy Central,” which threatens to blockade part of Hong Kong’s main business district.

Mass protests can paralyze this high-density territory. Business leaders have said that Occupy could damage businesses: Four of the largest multinational accounting firms placed advertisements in local newspapers warning against the movement, which has been branded illegal by Chinese authorities.

Occupy’s primary aim is to pressure China into allowing a truly democratic election in 2017.

Beijing says Hong Kong can go ahead with a vote in 2017 for the territory’s top leader. However, central Chinese government officials stress that Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, specifies that only a nominating committee can pick leadership candidates. Pro-democracy activists demand changes that would allow the public to directly nominate candidates.

Nearly 800,000 people voted in an unofficial referendum that ended on Sunday, which called for Beijing to allow open nominations of candidates for the 2017 poll — a vote China’s State Council, or Cabinet, called “illegal and invalid,” Xinhua news agency said.

Fears that the screws are tightening were heightened when Beijing published an unprecedented Cabinet-level white paper last month on Hong Kong. It bluntly reminded Hong Kong that China holds supreme authority over the territory.

“The high degree of autonomy of [Hong Kong] is not an inherent power, but one that comes solely from the authorization by the central leadership,” it said.

The policy document took about a year to prepare and was approved by the 25-member, decisionmaking politburo around a month ago, a second source close to Xi told reporters in Beijing.

It is a tricky issue for China’s new leadership. Hong Kong’s democratic experiment is seen as a litmus test of Beijing’s tolerance for eventual political reforms on the mainland, where calls for greater civil liberties and grassroots democracy have been growing, experts say.

Xi, who has swiftly consolidated power in China since taking office by taking a hard line on domestic and foreign affairs, is unlikely to compromise on Hong Kong, the sources close to him said.

“Hong Kong is no different,” the second source with ties to China’s leadership said. “Pushing for democracy in Hong Kong is tantamount to asking the tiger for its skin.”

China’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong is housed in a skyscraper stacked with surveillance cameras, ringed by steel barricades and topped by a reinforced glass globe. Soaring above streets filled with dried fish shops and small traders, it is known in Cantonese slang as “Sai Wan” a reference to the gritty western end of Hong Kong Island where it is located.

Each day, hundreds of staff, mostly mainland Chinese, stream into the matte gray building and its marble lobby with a large Chinese screen painting of pine trees.

Hong Kong is both part of China and outside of it, as defined in the 1984 Joint Declaration, the treaty under which Britain handed over its former colony.

“One country, two systems” — conceived by China’s then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) and then-British prime minister Margaret Thatcher — let Hong Kong keep its free-market economy and internationally respected legal system, with the exception of foreign affairs and defense.

SHADOW CABINET

As China’s on-the-ground presence in Hong Kong, the Liaison Office’s formal role is described in China’s recent white paper as helping to manage the Chinese government’s ties with the territory, as well as “communication with personages from all sectors of Hong Kong society.”

Two high-level sources with close ties to Leung say the Liaison Office does much more than that: It helps shape strategically significant government policies.

“The real Cabinet is the shadow Cabinet,” one source close to Leung said. “The chief executive’s office can’t do without the Liaison Office’s help on certain matters.”

The chief executive’s office did not directly respond to questions on the extent of its ties with the Liaison Office. It said in an e-mailed response that China and Hong Kong shared a close relationship on multiple fronts, including at “government-to-government level.” The office stressed Hong Kong’s autonomy and said that the Basic Law says no Chinese government body may interfere in Hong Kong affairs.

China’s Liaison Office did not respond to faxes and telephone calls seeking comment. The Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in Beijing, which has Cabinet-level authority over the territory from Beijing, did not respond to faxed questions.

The Liaison Office reportedly uses its broad networks, spanning grassroots associations, businessmen and politicians, to help the Hong Kong government push through policies needing approval from a largely pro-Beijing legislature. These have included the debate over democratic reforms in Hong Kong and a multibillion-dollar high-speed rail link to China, one source said.

Liaison Office heads were once rarely seen, but current director Zhang Xiaoming (張曉明) has taken on a far more public role since taking office 18 months ago — around the same time that Xi became China’s leader and Leung became Hong Kong’s chief executive. Zhang has lunched with legislators and also attends society gatherings alongside local tycoons and business leaders. Zhang did not respond to requests for comment.

Liaison Office staff, including some from the propaganda department, regularly telephone editors and senior journalists at Hong Kong media outlets.

Sometimes, these officials give what are known as “soft warnings” not to report sensitive topics, according to media sources and a report last year by the Hong Kong Journalists Association.

In one case, a television journalist was called by a Beijing official who mentioned an interview the journalist was planning.

The journalist “learned that this was a warning, meaning that he was ‘being watched’ and that he should not conduct sensitive interviews,” the report said.

COMMUNIST PENETRATION

Foreign diplomats and local academics believe the Liaison Office coordinates and implements the strategy of the CCP inside Hong Kong, although the hierarchy, membership and structure of the party in Hong Kong remain a secret.

Before the 1997 handover, the CCP focused on courting businessmen, academics and activists to secure influence and loyalty. It has now become more assertive, attempting to isolate party enemies, silence critics and deliver votes, Hong Kong academics and a source close to the Liaison Office say.

The vehicle for this strategy is a Beijing-based entity called the United Front Work Department, an organ of the CCP’s Central Committee, whose mission is to propagate the goals of the party across non-party elites.

The Liaison Office’s Coordination and Social Group Liaison departments report directly to Beijing’s United Front Work Department, according to a source in frequent touch with Liaison Office staff, who declined to be named.

“There is deeper penetration by the United Front in Hong Kong in recent years,” said Sonny Lo (盧兆興), an academic and author of a book on China’s underground control of Hong Kong. “In part, the United Front is working to counter and adapt to the rise of democratic populism and as a result we are seeing these new groups take to the streets.”

“United Front groups are being more heavily mobilized to not just support government policy but to counter rival forces,” he said.

A legacy of the earliest days of Leninist communist revolutionary theory, the United Front Work Department’s mission is to influence and ultimately control a range of non-party groups, luring some into cooperation and isolating and denouncing others, according to scholars of communist history.

“The tactics and techniques of the United Front have been refined and perfected over the decades and we are seeing a very modern articulation of it in Hong Kong,” says Frank Dikotter, a Hong Kong University historian and author of nine books on Chinese history.

The United Front — like the CCP itself — does not exist as a registered body in Hong Kong. There is no publicly available information about its network or structure. Neither the United Front Work Department in Beijing, nor the Liaison Office in Hong Kong, responded to questions from reporters about the purported activities of the front in Hong Kong.

However, it is possible to trace links from some grassroots groups to mainland-owned businesses and the Liaison office.

A Reuters examination of the societies registration documents for the Care for the Youth Group Association obtained from Hong Kong police show that the group’s chairman is Hung Wai-shing (洪偉成) and the vice chairman is Lam Kwok-on (林國安).

Police and corporate filings also show Hung is a director of a New Territories clan association that researchers believe is a core part of China’s United Front operations in Hong Kong’s northern fringes close to the Chinese border.

Hung is also a director of several Hong Kong subsidiaries of Beijing Yanjing Brewery Co, a state-owned Chinese brewery that stock exchange filings show is in turn majority owned by two investment vehicles ultimately tied to the Beijing city government.

Reports in the Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po dailies in Hong Kong — both mouthpieces for Beijing — have described Hung socializing with Liaison Office officials in the New Territories.

Hung denied any connection to the youth association when reporters visited him at his Yanjing Beer office in Hong Kong’s Fanling district.

“What you refer to, the Care for the Youth association, I tell you I’m not involved,” said Hung, a lean, middle-aged man with bushy eyebrows and thinning hair, who then called the police to complain about being questioned.

Lam is a regular at the anti-Falun Gong protests on Sogo corner. He ignored questions from reporters about his role with the youth association at a recent demonstration.

Other street groups, including the one that opposed Hong Kong’s Tiananmen commemoration, are run by individuals linked to a network of business chambers and associations in Hong Kong, including some that are at the vanguard of United Front work in the territory, academics say.

The chairman of one of those groups, the Voice of Loving Hong Kong, Patrick Ko (高達斌), is shown in company filings to be a director of the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, which the researcher Lo identified as an organization under the United Front umbrella in Hong Kong.

Ko denied any ties to Beijing’s United Front Work Department.

He said his group and the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce were “run by Hong Kong people.”

SECRET AGENTS

Behind the scenes, agents from Beijing’s powerful Ministry of State Security are also expanding China’s reach into Hong Kong, diplomats and members of various professions say.

The ministry sits at the apex of China’s vast security apparatus, responsible for both domestic and external secret intelligence operations.

Professionals in Hong Kong have been invited, often discreetly through intermediaries, to “drink tea” with agents.

The visits of these agents, who travel into Hong Kong on short-term permits, have become more frequent and their tactics more assertive, say multiple sources who have had contacts with such agents.

Their targets are said to include Hong Kong-based priests, journalists, lawyers, businessmen, academics and politicians.

Two sources said that the agents offer gifts in exchange for information and favors.

“They said they have an unlimited budget” for gifts, one Hong Kong-based professional in regular contact with agents said.

Two priests said they received repeated visits from state security agents after recent tensions between China and the Vatican stemming from China’s moves to ordain bishops without the consent of the Holy See.

One priest recalled meeting a young and polite agent who “said he was a friend who wanted to help” while making it clear he was reporting to Beijing for state security.

“It was clear he wanted secrets — gossip and views about [Hong Kong] relationships and trends and what might be going on at the Holy See,” said the priest, who declined to be identified.

In recent months, the agents have been asking about the Catholic Church’s support for the Occupy Central movement, two priests said.

The ministry did not answer calls to its main telephone number in Beijing; the government does not disclose other contact numbers for the ministry to foreign reporters.

While the battle for influence continues, there is no let up on Sogo Corner for Lau and her fellow Falun Gong devotees.

On a recent Saturday, not far from where Lau was standing, members of the Care for the Youth Group Association held a “wanted” poster carrying Lau’s photograph with the words “evil cult member” below it.

Lam raised his portable loudspeaker rigged to a car battery.

“Wipe out the evil cult Falun Gong,” he shouted, his voice reverberating down the busy street.

Lau, however, would not be deterred.

“People can see we only want to make ourselves heard. Hong Kong should give us that freedom,” she said.

Additional reporting by Yimou Lee

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama