As Yuka Takeda sat down with members of Kazakhstan’s government earlier this year in the capital, Astana, to discuss poverty levels, the Japanese economist noticed a stark contrast with her experience back home.

It was not the difference in culture or the gap in economic development; it was that seven of the eight lawmakers attending the meeting were women. Coming from Japan, where men outnumber women at universities by almost six to one in her discipline, Takeda had almost abandoned the idea of a career in academia when she was studying economics in college.

She wanted to go to grad school, but “I just couldn’t imagine how I could build a career in the field,” Takeda, 41, said in an interview in Tokyo. She had no female role models in Japan, “absolutely zero,” she said.

So she began applying for jobs in business while still a student at the University of Tokyo. Then she learned she had won one of the top awards for her thesis, giving her the courage to pursue her dream of post-graduate studies on Russia at the college. It was the first step in a career that led Takeda to the former Soviet states and to write a book on poverty that re-examined economic thinking on the development of wealth gaps, winning her the Masayoshi Ohira Memorial Prize last year.

The award, named after a former Japanese prime minister, recognizes books on politics, economics, culture and technology that advance the development of the Pacific Basin community.

“Before her, few scholars did statistical analysis on how Russia’s households were financially affected in the transition and suffered poverty,” said Toshio Watanabe, chancellor of Takushoku University in Tokyo and a judge for the prize. “Her work was quite an achievement. I wish there were more young scholars like her.”

Takeda’s interest in Russia had been sparked as an undergraduate by the memoirs of Anna Larina, wife of revolutionary Nikolai Bukharin, who was executed under former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in 1938. Larina was separated from her one-year-old son and spent two decades in prison camps and in exile.

“I was deeply touched by her life, which was overwhelmed by circumstances and at the mercy of events that she could not resist,” Takeda said.

As a new era of turmoil overtook Russia in the 1990s, Takeda wondered how Russians were coping with unemployment in the post-Soviet economic meltdown.

“I got hooked on the topic from that simple question,” said Takeda, a research fellow at Waseda University in Tokyo. “In economics, as in other fields, we’re attracted to the issues of the time we live in.”

When she enrolled at graduate school in 1997, her knowledge of Russian “was non-existent,” she said. She had chosen French as her foreign language as an undergraduate. To catch up with her classes, she spent a fortnight in the library beginning to teach herself Russian grammar from books.

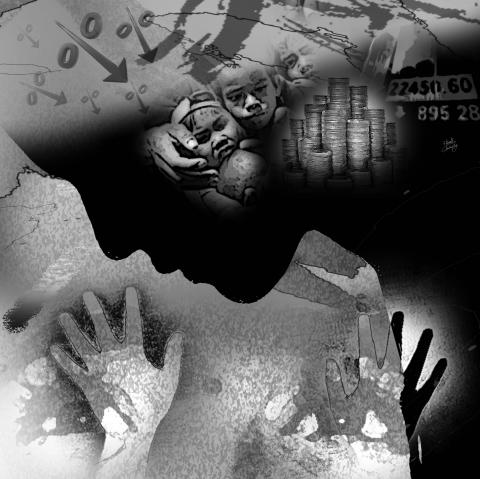

Poverty analysis is a relatively recent field of study in Russia because Soviet-era propaganda claimed it did not exist. After the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991, the country’s wealth gap expanded rapidly as oligarchs profited from the nation’s natural resources, while many pensioners and unemployed saw their assets vanish with the currency’s collapse.

As the Russian government began to publish more economic statistics, including data on household spending and finances, Takeda’s research intensified. In 2001, she moved to Moscow to better learn the language and deepen her postgraduate studies.

“We are still far from understanding the ways in which individuals and communities find themselves being trapped into poverty,” said Vladimir Gimpelson, director of Moscow’s Centre for Labour Market Studies at the National Research University Higher School of Economics. Gimpelson, who was Takeda’s academic adviser in Russia, first met her when he taught at Tokyo University in 1998.

“Takeda made a significant contribution to this research. Her work puts into question the issues that have been treated as stylized facts by other researchers and finds that reality is more complex,” Gimpelson said.

Takeda’s book, Economic Analysis of Poverty in Transitional Russia: A Microeconometric Approach, argues from data collected in Russia that households whose economic conditions are declining reach a tipping point beyond which they fall rapidly into poverty.

She also argued against the prevailing belief that the country’s economic expansion was pro-poor, demonstrating that most of the benefits accrued to the rich because there were few mechanisms to let growth trickle down to lower-income households.

“Backed by her language skill and experience of living in the country, she succeeded in conveying perceptions of Russian people’s daily life of the period, which bleak data analysis can never provide,” said Watanabe, the Ohira award judge.

Despite her library studies, Takeda had little spoken Russian when she arrived in Moscow and learned by staying in the apartment of a radio journalist and his family. She also got a taste of some of the hardships Muscovites endured at the time, such as having no hot water for weeks and being trapped in the dark in a faulty elevator.

In Kazakhstan in late 2011, her computer stopped working in her hotel, prompting a taxi driver to jokingly suggest that, in his country, winter is cold enough to freeze even the Wi-Fi signal.

In both countries, she noticed how many people she worked with were women. Moscow’s statistics department and social-policy research institute were “almost an environment for women only,” said Takeda, whose two-year stay in the country contributed to her love of gymnastics and figure skating.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe last month proposed increasing women’s participation in the workforce as part of his economic-growth strategy. Women account for 14 percent of researchers of all fields in Japan, trailing 42 percent in Russia and 34 percent in the US, according to a Japanese government white paper on gender equality published in June.

The higher proportion of female researchers in Russia does not translate to greater equality in power. Only 14 percent of legislators in Russia last year were women, and 24 percent in Kazakhstan, according to the World Bank. The shares are still higher than in Japan, where just 8 percent of lawmakers in the Diet were female.

It is hard for women to obtain tenure or a stable position at a Japanese university, according to Takeda.

“It takes time to secure positions even if your academic achievements are highly valued,” she said. “When the issue of employment comes around, I think there is a difference. We can’t deny that it’s harder for a woman.”

Takeda returned to Japan in 2003, working as a research associate at Tokyo University and teaching at Waseda University and Hitotsubashi University as an assistant professor.

Her work in Russia led to an invitation from the International Labour Organization (ILO) to join a research team in Kazakhstan in 2011 to make a policy recommendation on how to define a subsistence level in the country.

“Takeda’s Russian experience and language skills made her ideal for the post,” said Mariko Ouchi, an official at the ILO’s Country Office for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, who has known Takeda for more than 10 years. “It was convinced that she was the one who ideally met all of the requirements.”

Her first conference call with fellow project members took place on March 11, 2011, the day of the earthquake that caused the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactor. She made three trips to the Central Asian country in the following two years and the Kazakhstan government has used the research to help formulate social-welfare policy.

The daughter of an architect and a housewife in Tokyo, Takeda said she has been interested in issues of fairness and equality since she was a child. She was in high school when she first saw her favorite film: the 1947 Academy Award-winning Gentleman’s Agreement, in which Gregory Peck plays a journalist investigating anti-Jewish discrimination in the US.

“Economics was a way to equip myself with tools to realize social justice,” she said.

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural