At an organizing breakfast for National Rifle Association (NRA) grassroots activists, Samuel Richardson, a man with whom I have not exchanged a word, passes me a note.

“Please read the book Injustice by Adams,” it reads. “He was [sic] lawyer for US Justice Department who prosecuted Black Panther Case.”

Quite why Richardson thinks this book is for me is not clear. There are six other people at the table, a couple of them journalists. That I am the only black person in a room of around 200 may have something to do with it.

Christian Adams, a former US Department of Justice lawyer, resigned after the department decided not to prosecute members of the New Black Panther party who brandished guns and intimidated poll watchers outside a voting station in Philadelphia in 2008. Several attorneys, including Republicans, have argued that while the case was serious it did not warrant the department’s resources. Adams believed there were darker forces at play, claiming the case “gave the public a glimpse of the racially discriminatory worldview” of the department under Obama.

Richardson goes further. The press and the government are in cahoots, he explains, to oppress white people.

“It’s fascistic,” he explains. “It’s just like Hitler did. Discriminating against one ethnic group and claiming that they’re the cause of everything that’s wrong. It’s what happened in Rwanda,” intimating that white Americans, like Tutsis, could one day find themselves systematically slaughtered in their own land.

It would be easy to ridicule the NRA. Billboards for its national convention all around St Louis promise “acres of guns and gear.” In the exhibition hall they are giving two free guns, twice a day, to anyone wearing a sticker that says “Ambush.” They also sell semi-automatics in pink camouflage. One of the most powerful lobbying organizations in the country and deeply embedded in the Republican party, the NRA still calls itself the US’ oldest civil rights organization.

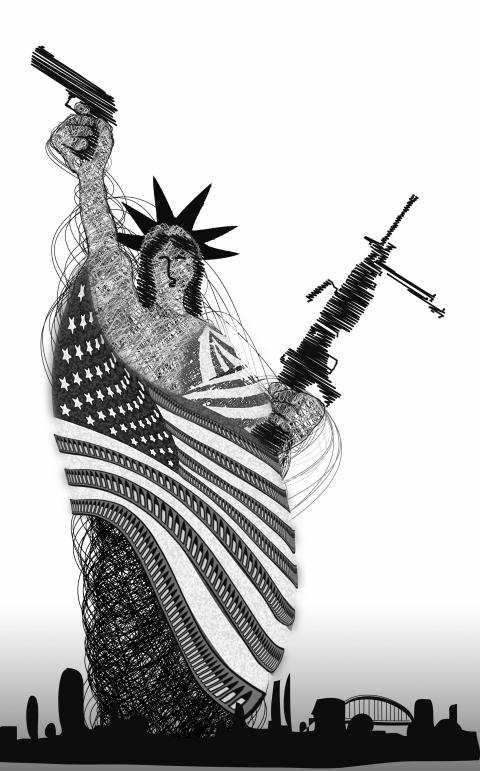

However, the US’ relationship with guns is as deep and complex at home as it is perplexing abroad. That most British police are not armed confounds even the most liberal Americans and even though the US is evenly split on whether there should be more gun control, every time there is a gun-related tragedy, whether it is the shootings in Arizona, Virgina Tech or any number of schools, the issue has been effectively removed from the electoral conversation. And at the center of these apparent contradictions stands the NRA, once an organization that represented the rights of hunters and sportsmen and now a major political player closely linked to the gun industry.

“All the domestic controversies of the Americans at first appear to a stranger to be incomprehensible or puerile,” suggested the 19th-century French chronicler Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. “And he is at a loss whether to pity a people who take such arrant trifles in good earnest or to envy that happiness which enables a community to discuss them.”

However, guns in the US are no trifling matter. There are approximately 90 guns for every 100 people in the US (a rate almost 15 times higher than England and Wales). More than 85 people a day are killed with guns and more than twice that number injured with them. Gun murders are the leading cause of death among African Americans under the age of 44.

The NRA is no joke, either. Claiming gun ownership as a civil liberty protected by the Second Amendment, it opposes virtually all gun control legislation. It claims more than 4 million members, has an annual budget of more than US$300 million and spent almost US$3 million last year — when there were no nationwide elections — on lobbying.

The Second Amendment to the US constitution reads: “A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

There has long been a dispute about whether “the people” described refers to individuals or the individual states, but there is no disagreement about its broader intent, which is to provide the constitutional means to mount a military defense against a tyrannical government.

“It’s about independence and freedom,” explains NRA member David Britt. “When you have a democratic system and an honorable people then you trust the citizens.”

Britt, an affable man in his 60s, does not lend himself easily to caricature. Elsewhere in the room, one T-shirt quotes Thessalonians 3:10 (“If any would not work neither should he eat”) on the back and “I hate welfare” on the front. Another T-shirt announces: “Christian, American, Heterosexual, Pro-Gun, Conservative. Any Questions?”

Britt is more understated, conservative and more likely to water at the mouth talking about barbecue in his native Memphis than foam at the mouth over a Fox News talking point. He does not fetishize guns, but fondly recalls his grandfather giving him his first rifle when he was seven.

“He said it’s not a toy and he showed me how to use it properly,” he said.

Britt believes individual gun ownership is a guarantor of democracy.

“In Europe they cede their rights and freedoms to their governments, but we think the government should be subservient to us,” he added.

For all the right-wing demagoguery associated with the NRA, this is quite a radical notion. The trouble is that, left in the hands of individuals, each gets to define their own version of tyranny and potentially undermine democracy with their firearms. Some believe the healthcare law enacted by the democratically elected US Congress is tyrannical.

In the hardscrabble town of Pahrump, Nevada, in 2010, I witnessed a conversation between conservatives about the most propitious moment to militarily challenge this government.

“The last thing we want to see is to break out our arms,” one said. “But we need to have them in hand, and the government needs to know that we will use [our arms] if they continue down the path they’re on.”

The Second Amendment is not the only factor that embeds guns in the US’ culture. As a settler nation that had to both impose and maintain its domination over indigenous people to acquire and defend land and feed itself in a frontier state, the gun made the US, as we understand it today, possible.

“None of us in the free world would have what we have if it were not for guns,” Britt says. “It’s about freedom, it’s not about violence.”

Missouri representative Jeanette Oxford, who represents a district in St Louis, disagrees.

“From the outset violence was enforced with weapons of various kinds in North America,” she says. “I think the ability to enforce your right through might is ingrained in us.”

It is also an important component of something else that is central to US society: capitalism. Guns make money. A lot of it. Since 1990 the sale of legal guns alone has come to, on average, about US$3.5 billion every year. And it is recession-proof, rising and falling less with the economic tide than the electoral one. When Democrats are elected the sales go up, and when a black Democrat is elected, they skyrocket. The week US President Barack Obama was elected gun sales leaped 50 percent against the previous year, and they have continued to rise sharply.

In the exhibition hall at the convention, the industry is showcasing its arsenal. As well as rows of semi-automatic weapons of all colors and sizes there are tables with a range of handguns and accessories: Eagle grips in ultra pearl black and ivory polymer, Hornady bullets (“accurate, deadly, dependable”) and general appeals to the rustic, manly and patriotic.

A few blocks away at St Louis City Hall, some of the survivors of the shooting in Tucson last year are staging a press conference to call for greater gun control. Some are gun owners themselves. Mavy Stoddard, 77, wept as she recalled the death of her husband Dorwan, 78, one of the six people killed that day, who covered her with his body when gunfire erupted.

“He fell on top of me,” she said. “He was shot through the temple. Somehow I got out from under him and held him on my lap for seven or eight minutes before he died.”

The tone is not strident, but plaintive. No one here wants to touch the Second Amendment or is calling for wholesale reform of the gun laws. Mavy cannot understand why the NRA leadership will not even take her calls or sit down to discuss the issue with her. St Louis has been named the most dangerous city in America for two years running and leads the nation in black homicides. Three years ago, Ernecia Coles, 40, was bidding farewell to business associates in the historically black neighborhood of Ville when shooting erupted.

“I got hit by a stray bullet. It went under my left ear, zig-zagged through my soft tissue, went through my neck and exited my right jaw,” she said.

Coles grew up around guns in rural Virginia. Her father had one for protection, but in a city such as St Louis, she says, they play a different role.

“For now, the risk of gun violence is the price you pay for working and living in urban America,” she said.

Elizabeth Watkins lost two of her sons to gun violence. The first, Timothy, 28, was shot after a fight in Miami in 1990. The second, Mark, also 28, was caught in crossfire, while visiting a friend in St Louis. As spokesperson for Families Advocating Safe Streets, Watkins used to attend funerals of those who fell to gun violence in the city.

“I had to stop going after a while,” she said. “I couldn’t take it any more.”

Despite their experiences, neither is calling for root-and-branch reform.

“I’m not saying people shouldn’t be able to protect their property, but guns are too available to young people,” Watkins said.

Coles believes the NRA should be “compelled to examine and address the unintended consequences that that constitutional right has brought about in many American communities and against too many innocent American citizens.”

Given the scale of the problem, one is struck by how modest many of these demands are. Yet the mantra from NRA enthusiasts and others is that guns do not kill people, people kill people. This banal iteration conveniently ignores the fact that people can kill people far easier with guns than almost anything else and that, in a country with high levels of inequality, poverty and segregation, such as the US, they are more likely to do so.

It also does not account for the NRA’s role in pushing legislation such as stand-your-ground laws that allowed George Zimmerman, Trayvon Martin’s killer, to walk free for more than six weeks. The law states that anyone who perceives a threat to their life has a right to use a weapon. The core of the debate over the last few weeks has not been Zimmerman’s right to bear arms, but that the law now on the books in more than 20 other states protected him from even being arrested for so long and makes it difficult to prosecute.

The day registration opened at the NRA, Zimmerman’s face peered from every newsstand following his arrest, but the case barely came up unless raised by a journalist.

There was some contrition — “It’s a tragedy. It shouldn’t have happened, but I think the media has exploited it,” Britt said — but also some defiance:

“He was attacked and he defended himself,” Richardson said, before going on to say that nobody knows all the facts and returning to the problem of the New Black Panthers.

Back at the grassroots breakfast the organizers are gearing up the activists for this election year. “Bad people get sent to Washington because good people don’t vote,” they say. When it comes to engaging potential allies they are told to “hunt where the ducks are” — gun clubs, hunting groups and so on. Each electoral district has an assigned Election Volunteer Coordinator who acts as a go-between among candidates, members and gun owners. Few domestic organizations can rival the NRA in lobbying power.

Liberal legislators recognize and respect its influence precisely because it is so effective.

“They don’t have shoot-ins and rifle marches,” explains Massachusetts Democrat Barney Frank. “They write and call. The NRA — person for person — they are extremely influential because they lobby that way.”

In 2000, Democrats credited the NRA with swinging the election for George Bush by costing Al Gore his home state of Tennessee. It was around that time that Democrats, as a party, effectively gave up on gun control. Obama, during his first two years, signed laws allowing guns in national parks and on checked baggage on trains. In 2010 he was graded “F” by the gun control group Brady Campaign. The NRA has not won the argument — only a tiny percentage believe, like the NRA, that controls are too strict and a plurality want to make them stricter — but they do keep on winning the votes.

Halfway through the session a slide displays the four people they consider the most important obstacles to their cause. Obama, US Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton (sitting in front of a UN flag), Eric Holder, Obama’s black attorney general and Sonia Sotomayor, the Latina supreme court judge. All, by their titles, are legitimate targets for the NRA, and yet one could not help sense the symbolic significance. Two women and three people of color in positions of authority — in a country where women are becoming more politically assertive and white people will be a minority in 30 years — looking down on a room filled overwhelmingly with ageing white men defending their right to bear arms.

The NRA is not entirely certain what to do with its partial success. Partly, it keeps pushing for laws that would expand the places where guns might be carried, including churches, bars and college campuses (it supports a group called Students for Concealed Carry). Partly, it opposes even the most basic controls, such as legislation to ban gun sales to people on the government’s terrorist watchlist, meaning a suspected terrorist can be denied the right to board a plane, but not to buy a gun.

This has left the NRA with a problem. Now the Democrats have caved and the supreme court has a pro-gun majority, it simply has no worthy enemy. No one at the convention can point to a single concrete piece of legislation from the White House that they did not like. Instead, they simply raise the specter of an Obama second term. Unfettered by the need to stand again, he will come for your guns.

It is this fear, of the unknown and the known, both manufactured, exploited and real, that hangs over the convention. Time and again people paint scenarios in which I or my family might be attacked, threatened or violated as a rationale for arming myself. In this atmosphere, Richardson’s evocation of Rwanda, while extreme, is not entirely ludicrous.

“Ultimately it comes down to whether you trust other people or not,” one gun control activist says. “We do, they don’t.” The ideas that the government might protect you, that the police might come, that if nobody had guns then nobody would need to worry about being shot, are laughed away.

“By the time you call the police it could be too late,” said Britt, who has never pulled a gun on anyone, but has had to make it clear he might a few times. “All they can do is write the report.”

When the breakfast is over I tell Britt that I am heading into town to see some people.

“Be careful,” he says. “St Louis is a very dangerous place.”

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) in recent days was the focus of the media due to his role in arranging a Chinese “student” group to visit Taiwan. While his team defends the visit as friendly, civilized and apolitical, the general impression is that it was a political stunt orchestrated as part of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda, as its members were mainly young communists or university graduates who speak of a future of a unified country. While Ma lived in Taiwan almost his entire life — except during his early childhood in Hong Kong and student years in the US —

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on Monday unilaterally passed a preliminary review of proposed amendments to the Public Officers Election and Recall Act (公職人員選罷法) in just one minute, while Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) legislators, government officials and the media were locked out. The hasty and discourteous move — the doors of the Internal Administration Committee chamber were locked and sealed with plastic wrap before the preliminary review meeting began — was a great setback for Taiwan’s democracy. Without any legislative discussion or public witnesses, KMT Legislator Hsu Hsin-ying (徐欣瑩), the committee’s convener, began the meeting at 9am and announced passage of the

Prior to marrying a Taiwanese and moving to Taiwan, a Chinese woman, surnamed Zhang (張), used her elder sister’s identity to deceive Chinese officials and obtain a resident identity card in China. After marrying a Taiwanese, surnamed Chen (陳) and applying to move to Taiwan, Zhang continued to impersonate her sister to obtain a Republic of China ID card. She used the false identity in Taiwan for 18 years. However, a judge ruled that her case does not constitute forgery and acquitted her. Does this mean that — as long as a sibling agrees — people can impersonate others to alter, forge

In response to a failure to understand the “good intentions” behind the use of the term “motherland,” a professor from China’s Fudan University recklessly claimed that Taiwan used to be a colony, so all it needs is a “good beating.” Such logic is risible. The Central Plains people in China were once colonized by the Mongolians, the Manchus and other foreign peoples — does that mean they also deserve a “good beating?” According to the professor, having been ruled by the Cheng Dynasty — named after its founder, Ming-loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) — as the Kingdom of Tungning,