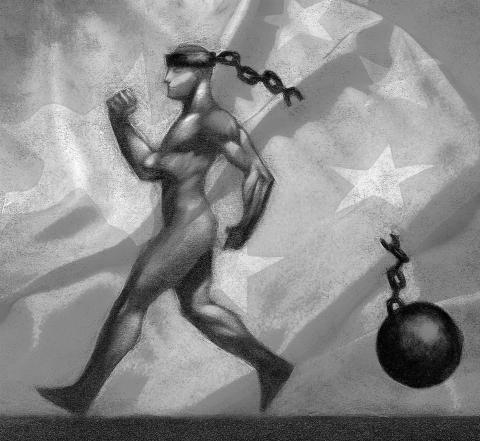

The village of Wukan waits surrounded by what will be one of Chinese President Hu Jintao’s (胡錦濤) most far-reaching, yet contested legacies: A vast buildup of the domestic security apparatus that critics say feeds the discontent it was designed to defuse.

Riot police penning in the people of Wukan, Guangdong Province, who have protested for a week about farmland seized for development and the suspicious death of a village organizer, form one part of Hu’s drive for “stability preservation” that reaches from dissidents detained in China’s capital to restive corners of the countryside.

Since February, Hu has redoubled the urgency of his campaign to strengthen “social management” and pre-empt unrest before he retires from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership late next year and from the state presidency shortly after that.

“When we look back, the defining feature of Hu Jintao’s era will be stability preservation. That will be the term through which his era is remembered. It will be his legacy,” said Cui Weiping (崔衛平), a 55-year-old dissident-writer in Beijing, who lives monitored by a team of security police — another part of the security drive.

“Stability preservation is the party’s defensive response to a society that is growing more fluid and assertive, but the system can’t keep up with social change and public demands,” Cui said.

“That’s why they’re so anxious despite all the security spending,” she said, adding that she has become a prisoner to this push.

“Somebody controls my cellphone, my computer and Internet, when I can step outside and when I must stay in,” Cui said.

In many ways, Wukan distills official fears. The village lies on a relatively prosperous and connected edge of the urbanizing coast, not a desperate corner of the interior.

Hu and other leaders have often warned officials to prepare for greater risks to party control as China’s citizens become more mobile, more connected on the Internet, more wealthy and more vocal against inequality and corruption.

While Chinese policymakers in many areas tread water before the leadership succession, security officials led by CCP Central Political and Legislative Committee Secretary Zhou Yongkang (周永康) have issued directives and held meetings every week aimed at bolstering “social management,” the party’s phrase for defusing sources of discontent and enhancing controls.

Hu has also overseen a jump in spending on policing and law-and-order agencies, and expanded the powers of the domestic security hierarchy that yokes local officials’ prospects for promotion to their success in pre-empting potential unrest.

“Strengthening and renovating social management is an urgent task to preserve social harmony and stability,” Zhou told officials in September, according to Xinhua news agency.

He called the campaign — which has been given added urgency by upheavals rippling from the Arab world — a strategic task to “consolidate the ruling status of the party” and protect order.

“With the 18th Party Congress coming up and the handover of power so sensitive, they don’t want any destabilizing incidents,” said Xie Yue (謝岳), a professor of political science at Tongji University in Shanghai, who has studied “stability preservation” (weiwen) policies.

The congress convenes late next year.

“Social management entails taking the offensive to attack sources of unrest before they even break out,” Xie said. “To some extent, it’s a substitute for political reform.”

Yet the push could sow the seeds of its own undoing and bring worse unrest in its wake by breeding corruption, deterring the government from embracing reforms, skewing spending and numbing officials to chronic discontent, said analysts who have studied the expansion of China’s security state.

“[Chinese Vice President] Xi Jinping (習近平) will take over a big system of internal security and surveillance, the biggest in the world, but it probably doesn’t work in the long-run,” said Borge Bakken, a sociologist at the University of Hong Kong studying the “social management” drive.

Xi is Hu’s mostly likely successor.

“If everything is about social control, then it goes against good governance, but it might last a long time, simply because of the massive bureaucratic incentives now built into stability preservation,” Bakken said.

HU REALLY WORRIED

China’s leaders worry that the thousands of local protests and riots across the country every year could over time congeal into bigger and sustained movements that could truly challenge party power.

No official counts of the number of protests, riots and mass petitions have been released in recent years, but most estimates in government-sponsored studies put such “mass incidents” at about 90,000 a year in recent years.

In 2007, China had more than 80,000 “mass incidents,” up from more than 60,000 in 2006, according to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. In 1993, the government counted 8,700, although shifts in definitions, counting methods and sheer official attention to unrest prevent strict comparisons.

Most citizens still focus their ire on specific grievances and the local officials they hold responsible for them. However, party leaders’ worries that grassroots discontent might congeal into political opposition have been magnified by uprisings against authoritarian governments across the Arab world.

The Wukan villagers’ demands for a return of their former farmland have been mixed with some calls for democratic village elections — a sign of politicization that could further alarm party officials.

Hu gathered together senior party officials in February and set out his plans for a campaign to overhaul “social management” and ensure government control does not flounder in a fast-changing society.

Hu’s message — delivered in the opaque words of party doctrine — was that rising prosperity would not automatically win the government support. On the contrary, the rapids of economic change could embolden citizens and upend controls.

Since then, Hu’s chief official in charge of domestic security, Zhou, has almost daily issued directives and speeches and attended meetings to lock in place strengthened “social management” as a policy priority.

“Hu Jintao seems to be just kind of playing out time, so I was surprised to see him with such a strong initiative, which led me to the conclusion that the leadership really is quite worried about this,” said Joseph Fewsmith, a professor of Chinese politics at Boston University in Massachusetts.

“People seem much more willing to challenge the authority of local government,” said Fewsmith, who has written an unpublished paper on China’s “social management” campaign. “They all seem to chip away at the legitimacy of the government.”

“I think it means they’re hunkering down and they’re not going to compromise and pursue the sorts of political reform their critics say they need to do,” Fewsmith said.

PUBLIC SECURITY BOOM

A big part of Hu’s answer to these worries is displayed on Beijing’s central thoroughfare, Changan Avenue: The Chinese Ministry of Public Security — a hulking symbol of the power of the domestic security system, which was finished several years ago and is larger than the nearby parliament building.

After Hu first succeeded Jiang Zemin (江澤民) as party leader in late 2002, he and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao (溫家寶) encouraged hopes among some that they might seek to defuse smoldering social tensions by measured political relaxation and legal reforms.

However, since 2007, their populist gestures have become increasingly overshadowed by the push to expand domestic security spending, stifle dissent and deter the tides of petitioners traveling to Beijing in the hope that central officials will heed their complaints about land seizures, corruption and police abuses.

“China has always been a heavily controlled place, but what’s new is the scale of it, the way in which the government has pushed this as an alternative to the emergence of a real civil society,” Bakken said.

China’s projected budget this year for domestic “public security” — a gauge of spending on “security preservation” —- outstripped the defense budget for the first time.

The 13.8 percent jump in China’s planned budget for police, state security, armed civil militia, courts and jails brought planned spending on law and order items by the central and local governments to 624 billion yuan (US$98 billion) — more than twice Uruguay’s GDP.

The Chinese Ministry of Finance said last month that the growing budget for public security was normal and included items other than “security preservation,” Xinhua reported.

However, Xie said the ministry’s own definitions and data showed the “public security” budget goes overwhelmingly to anti-riot forces, police and other law-and-order agencies.

“Denying that stability preservation is a large and growing outlay for the government simply isn’t true,” Xie said.

The spending jump has paid for more police, surveillance cameras, and anti-riot forces brandishing advanced equipment. More than 104 billion yuan of the public security budget went to the People’s Armed Police, the domestic militia, Caijing magazine, a Chinese publication, reported last month.

Shanwei, the administrative area that oversees Wukan, follows that national pattern. Shanwei’s domestic security budget has grown to 121 million yuan, an increase of 18 percent from last year, according to the local government’s Web site.

That was more than 50 percent greater than the projected budget for education and about three times the budget for healthcare.

China’s domestic security spending has been buttressed by steps to add clout to domestic security officials and their agenda under Zhou. In Shanwei and other areas, many local governments have opened “stability preservation” offices intended to monitor and defuse discontent.

Yet all that spending did not stop Wukan from becoming a stubborn holdout against the government.

The death in custody over a week ago of village protest organizer, Xue Jinbo (薛錦波), ignited fresh protests that forced police and officials to abandon the semi-urban village.

Even some officials and party-run publications have said that the pattern of “stability preservation” leading to further unrest is repeated far too often across China.

“By believing that stability takes absolute priority, and even paying no heed to stability preservation costs and ramifications, our organizational capacities become trapped in a vortex,” a commentary in the CCP newspaper the Study Times said in August.

Central government demands that local governments pour more funds into “stability preservation” create additional burdens on local centers and divert spending from welfare programs that could better defuse public discontent, said Xie, who recently finished a book-length study of the issue.

“They have a motive to present a very grim outlook for public security in order to enhance their revenues and status, but that actually exacerbates the problems threatening social stability,” Xie said of China’s domestic security system.

REFUSING TO BE MANAGED

Xi will have to decide whether he wants to stick to this path.

Xi was in charge of security for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing and shows no sign of wavering from the imperative to protect the CCP from any potential challenges.

However, Cui said the stability drive would ultimately buckle under the weight of costs, corruption and pent-up social pressures. Wukan could be a forerunner of what Xi must confront.

“I don’t know how or when the era of stability preservation will come to an end, but when it does, there will surely be major changes,” she said. “You can’t manage a society that refuses to be managed.”

Within Taiwan’s education system exists a long-standing and deep-rooted culture of falsification. In the past month, a large number of “ghost signatures” — signatures using the names of deceased people — appeared on recall petitions submitted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) against Democratic Progressive Party legislators Rosalia Wu (吳思瑤) and Wu Pei-yi (吳沛憶). An investigation revealed a high degree of overlap between the deceased signatories and the KMT’s membership roster. It also showed that documents had been forged. However, that culture of cheating and fabrication did not just appear out of thin air — it is linked to the

On April 19, former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) gave a public speech, his first in about 17 years. During the address at the Ketagalan Institute in Taipei, Chen’s words were vague and his tone was sour. He said that democracy should not be used as an echo chamber for a single politician, that people must be tolerant of other views, that the president should not act as a dictator and that the judiciary should not get involved in politics. He then went on to say that others with different opinions should not be criticized as “XX fellow travelers,” in reference to

Taiwan People’s Party Legislator-at-large Liu Shu-pin (劉書彬) asked Premier Cho Jung-tai (卓榮泰) a question on Tuesday last week about President William Lai’s (賴清德) decision in March to officially define the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as a foreign hostile force. Liu objected to Lai’s decision on two grounds. First, procedurally, suggesting that Lai did not have the right to unilaterally make that decision, and that Cho should have consulted with the Executive Yuan before he endorsed it. Second, Liu objected over national security concerns, saying that the CCP and Chinese President Xi

China’s partnership with Pakistan has long served as a key instrument in Beijing’s efforts to unsettle India. While official narratives frame the two nations’ alliance as one of economic cooperation and regional stability, the underlying strategy suggests a deliberate attempt to check India’s rise through military, economic and diplomatic maneuvering. China’s growing influence in Pakistan is deeply intertwined with its own global ambitions. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship project of the Belt and Road Initiative, offers China direct access to the Arabian Sea, bypassing potentially vulnerable trade routes. For Pakistan, these investments provide critical infrastructure, yet they also