It was a moment Roland Reed had long dreaded.

“Just Googled you, dad,” began the text from his daughter. “Why are all these people saying horrible things about you online?”

Reed stepped out of work, took a deep breath and dialed his daughter’s number. As calmly as he could, he explained that he wasn’t really a child abuser, but that someone on the Internet had it in for him. A cyberstalker had chosen Reed as his victim, apparently at random.

“I told her, ‘It’s just some nutter, ignore it,’” he says.

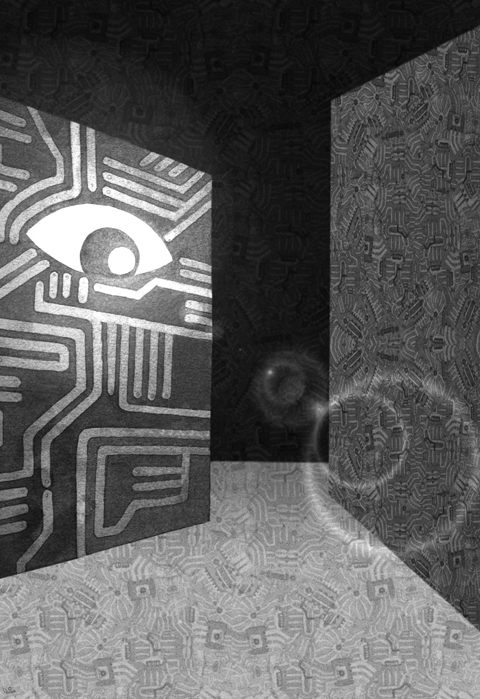

However, Reed himself couldn’t. Every night he logged on to the Internet to see what his stalker had been doing to destroy his reputation that day. The allegations were spreading insidiously on Internet forums and he was powerless to stop them. Even if he did have time to contact each site moderator — where one existed — there was no point, he believed. His stalker, posting from behind an untraceable proxy server, would just create a new identity and spring up elsewhere. Plus, he didn’t want this belligerent stranger to know that he cared. It would just feed their lust for attention and destruction.

Being accused of pedophilia is damaging for anyone, but for Reed, a 42-year-old youth worker, it was catastrophic. He had already warned his boss that someone had started a smear campaign against him, calling him a child molester on various message boards, and then adopting multiple personas to pile on to these forums and give the impression that lots of people agreed. Luckily, Reed’s boss believed him, but what about anyone else who was bored enough to enter his name into a search engine?

“Any time a work colleague gives me a strange look, I think, has he found this stuff about me on the Internet?” says Reed, who is still being targeted to this day.

People tend to think of cyberstalking as spying on a former or future lover. In the common parlance, it’s a relatively harmless, if slightly grubby, activity: Googling somebody before a first date, checking to see if an ex’s new girlfriend has failed to change her default Facebook privacy settings … that sort of thing. However, cyberstalking can be a crime, and starting on Friday, new guidelines in the UK from the country’s Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) recognize it as such. It has actually been prosecutable for more than a decade in England and Wales, under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997 and the Electronic Communications Act 1998, but the fact the CPS is now using the specific term in its advice to prosecutors will encourage the authorities to treat it as a serious issue worthy of judicial time.

Cyberstalking shares much with its offline cousin, but whereas “real life” stalkers almost always know their victims, usually intimately, but occasionally merely by sight, on the Internet there are more people who target individuals for no discernible reason — as Reed found out to his horror. It can describe any repetitive behavior that makes someone else feel uncomfortable or threatened; that might mean unsolicited e-mailing, instant messaging and spamming, or compiling a dossier of personal information about a person in order to harass, threaten or intimidate them. It might mean posing as someone else online, setting up a profile on a social networking site or an e-mail address that is similar to the victim’s own or, as in Reed’s case, the creation of an online smear campaign to blacken a victim’s name.

In the most recent British Crime Survey, published earlier this year, 18.7 percent of women and 9.3 percent of men said they had been stalked at some point in their lives. Half of all stalkers now use the Internet to contact or target their victims, according to research carried out by chartered forensic psychologist Lorraine Sheridan and the charity Network for Surviving Stalking last year.

That study found that “stalking conducted by an unknown someone over the Internet is just as damaging as stalking in the real world … All medical and psychological effects, and most social and financial effects, did not differ significantly according to cyber involvement.”

These include suicide attempts, aggression, paranoia, relationship breakdown plus the stress and expense of moving house and paying for therapy or counseling.

Reed agrees that cyberstalking is no lesser crime.

“It’s just as hurtful. The fact that it’s a faceless coward hiding behind the anonymity of the Internet is so frustrating. It allows them to do and say things they could never get away with in real life,” he says.

In addition, because it is easier to cyberstalk someone, but harder to assess the effect it has, cyberstalkers tend to ratchet up their activity, Sheridan says.

“Indeed, cyberstalkers may develop a tolerance to Internet-based harassment, requiring more extreme activity in order to achieve the same ‘rush,’” she wrote in the study, noting that “similar tolerances have been observed among Internet-using sexually addicted males.”

The existing laws in England and Wales are not specific to stalking (the harassment act includes disputes between neighbors, for example), making it hard to assess just how prevalent the problem is. The CPS insists its new guidelines will ensure that more stringent restraining orders are granted, for example, and discourage the authorities from dismissing stalking as a bit of unwanted, but essentially harmless, attention.

Experts agree that cyberstalking is a growing issue. In January, television producer Elliot Fogel was jailed for harassing Claire Waxman, an old college acquaintance. When police examined his computer after his arrest, they discovered he was using Waxman’s wedding photos as his screensaver, and he had Googled her 40,000 times in a year. Earlier this month, a woman called Alida O’Reilly was reported to be facing a restraining order for her alleged stalking of the BBC journalist Jeremy Vine. O’Reilly, who was also reported to be fixated on British politicians Liam Fox, Eric Pickles and David Cameron, superimposed herself into photos of Vine and posted them on her MySpace profile.

“The problem of stalking on the Internet is increasing and will continue to increase while we still take too many chances by allowing ready access to personal information on social networking sites,” says assistant chief constable Garry Shewan of the Greater Manchester Police, the Association of Chief Police Officers’ lead spokesman on stalking.

Compounding this, in the online space there remains confusion over activities that would seem creepy in the real world. People need to start making that comparison before they do something they might regret, says Emma Short, a psychologist at the University of Bedfordshire, who on Friday launched one of the largest ever research projects into cyberstalking.

“Quite a lot of people think it is acceptable to post compromising photographs of their exes online, yet they wouldn’t dream of photocopying the pictures and posting them on their door,” she says.

“My research has shown that everybody has an idea of the rules of the Internet, but the problem is that everyone’s idea is slightly different,” Sheridan says. “I gave a lecture recently where one girl said that she was considering calling the police because her ex-boyfriend had posted graphic photos of her on Facebook, and then another student said she had just split up with her boyfriend and had done the exact same thing. She said it was fine because ‘he had it coming.’”

Statistics from Sheridan show that just 4 percent of stalking victims are harassed online only. More often, stalkers use the Internet as another weapon in their armory. Sarah Jones, 38, was harassed by a work colleague who began by making inappropriate comments in the office.

“‘Your hair looks nice, but I preferred it longer’ — that sort of thing. Things that on their own don’t mean too much, but when added together revealed a disturbing pattern of behavior,” she says.

After Jones complained to the human resources department, her stalker started threatening to kill her in e-mails, calling her a “bitch” and a “whore,” and revealing that he had found out personal details about herself and her family. Sometimes the threats were written in Latin — it is a common tactic of cyberstalkers to use a foreign language, she has since discovered. She eventually reported him to the police and he pleaded guilty to harassment after telling police he had a plan to break into her house, rape and kill her and then kill himself. He was given a nine-month jail sentence.

Since his release, Jones has received a number of silent telephone calls. They were traced to phone boxes near his parents’ house, but there wasn’t enough evidence to prove he was responsible.

There is no one catalyst for cyberstalking. Reed’s ordeal began two years ago when he and his wife thought about buying a property in France. Unsure of the logistics, Reed decided to do some research, and stumbled across an Internet forum for Britons looking to purchase houses abroad. In a public post, he briefly introduced himself to other members using his first name only, and asked for advice on the French property market. A few days later he received a threatening personal message via the site.

“I just assumed it was a bored teenager getting up to mischief, so I sent back a reply along the lines of ‘go away, little boy’ and assumed that would be the end of that,” he says.

Responding, Reed believes now, was a mistake.

“It showed that I had noticed what he was doing,” he says.

Soon, he was receiving abusive messages and death threats from the same individual. One day, in a private message, the stalker announced that he had figured out Reed’s full identity, and trotted out his address, date of birth and wife’s name. Every detail was correct.

“I was horrified that someone would go to that extreme to find out information about someone they didn’t know. There was absolutely no logical reason for it,” Reed says.

But things soon got worse.

“One day a friend phoned me up and said, ‘Why are people writing stuff about you on the Internet?’ I didn’t know what he was talking about, so he told me to Google my name,” Reed says.

On a news forum a group of people appeared to be accusing him of being a pedophile. He quickly realized that the messages had almost certainly been written by the same individual.

“They all made the same grammatical errors and used phrases and pet words I recognized as coming from my stalker,” Reed says.

Each week the stalker would repeat the allegations on different forums, and Reed was powerless to act.

“Now I’ve had to stop torturing myself,” Reed says. “If I checked up on him every day I would make myself ill.”

This sort of smear campaign is a common tactic for cyberstalkers, though it is more usually carried out by someone with a grudge.

One woman cited in Sheridan’s study said: “I started to get vicious, hateful e-mails from a variety of addresses. All were anonymous and someone was pretending to be me and being vile to my clients. After about half a year of this, my ex started turning up and asked how my business was, quoting from these hateful e-mails. It was him who had sent them and he was so proud of himself! It was such a shock, as we had parted months before on, I thought, anyway, good terms.”

Other victims described how their stalkers had impersonated them on sex sites, giving their personal details out to men. Many talked of stalkers hacking into their e-mail accounts, creating their own versions of their Facebook pages, and sending offensive e-mails to people in their name.

Reed’s response was to try to remove all mention of himself from the Internet to stop his stalker finding out any more about him. That’s why told his boss what was going on, and requested that his name be removed from any electronic newsletters that might mention his youth work projects or include a picture of him.

“But you can’t stop third parties quite innocently mentioning me,” he adds. “I have discovered you can’t be ex-directory on the Internet.”

After taking legal advice, he decided it wasn’t worth reporting it to the police.

“The stalker is abroad in a different jurisdiction and there is no guarantee the police there would be able to do anything about it,” he says. “I just have to hope he will get bored and give up. That’s why I don’t ask forum moderators to delete his filth — then he would say, ‘Ha, ha! He is reading this’, and it will encourage him to carry on.”

Lack of reporting, though, is a huge problem Shewan said.

“One of the things we all agree on is to encourage victims of stalking to seek help, to contact the police and charities,” he says.

He adds that the police are hoping to work with Internet service providers in the coming year to encourage them to help users report harassment.

“The police and Internet service providers have a responsibility to do more,” he says. “If you look at child abuse, for example, there has been strong work in recent years that allows young people who feel they have been groomed or are upset about something said to them on the Internet to press online buttons that will alert Internet companies and criminal justice agencies. There are opportunities for similar types of processes to be set up.”

Everyone, he says, should think hard about what personal information they put online — something all victims agree on.

“Never give away your real name, even your first name,” Reed says, “and never give away your job or location. It’s preferable not even to reveal your gender. Definitely don’t put up photos. I’ve since discovered that my stalker has targeted others and posed as them on forums using their photo as his avatar.”

People need to become much more aware of the information they put out about themselves, Short says. We’re in a sort of anything-goes twilight zone, she suggests, where people don’t think they are really at risk.

“In a way, it’s a bit like when the HIV/AIDS campaign began and people didn’t think it could happen to them,” she says. “People need to understand that some of their behavior online opens them up to risk and modify it accordingly.”

Editor’s note: Some of the names have been changed.

To The Honorable Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜): We would like to extend our sincerest regards to you for representing Taiwan at the inauguration of US President Donald Trump on Monday. The Taiwanese-American community was delighted to see that Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan speaker not only received an invitation to attend the event, but successfully made the trip to the US. We sincerely hope that you took this rare opportunity to share Taiwan’s achievements in freedom, democracy and economic development with delegations from other countries. In recent years, Taiwan’s economic growth and world-leading technology industry have been a source of pride for Taiwanese-Americans.

Next week, the nation is to celebrate the Lunar New Year break. Unfortunately, cold winds are a-blowing, literally and figuratively. The Central Weather Administration has warned of an approaching cold air mass, while obstinate winds of chaos eddy around the Legislative Yuan. English theologian Thomas Fuller optimistically pointed out in 1650 that “it’s always darkest before the dawn.” We could paraphrase by saying the coldest days are just before the renewed hope of spring. However, one must temper any optimism about the damage being done in the legislature by the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), under

To our readers: Due to the Lunar New Year holiday, from Sunday, Jan. 26, through Sunday, Feb. 2, the Taipei Times will have a reduced format without our regular editorials and opinion pieces. From Tuesday to Saturday the paper will not be delivered to subscribers, but will be available for purchase at convenience stores. Subscribers will receive the editions they missed once normal distribution resumes on Sunday, Feb. 2. The paper returns to its usual format on Monday, Feb. 3, when our regular editorials and opinion pieces will also be resumed.

This year would mark the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the India Taipei Association (ITA) in Taipei and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center (TECC) in New Delhi. From the vision of “Look East” in the 1990s, India’s policy has evolved into a resolute “Act East,” which complements Taiwan’s “New Southbound Policy.” In these three decades, India and Taiwan have forged a rare partnership — one rooted in shared democratic values, a commitment to openness and pluralism, and clear complementarities in trade and technology. The government of India has rolled out the red carpet for Taiwanese investors with attractive financial incentives