He is bull-necked and barrel-chested, bald and foul-mouthed, the owner of a bejeweled Rolex and the hundreds of millions — perhaps billions — that go with it. His English is Russian-accented and salted with expletives. He is holidaying in Antigua, on a peninsula that he owns in its entirety. He is the kingpin in a brotherhood of Russian super-criminals, a financial whiz who until now has acted as a human Laundromat, expertly washing clean his fellow crooks’ soiled fortunes. However, now he has made covert contact with the British authorities: He wants to be an informant, a mega-grass who will reveal the secrets of the dark underworld he has inhabited for so long.

If that sounds like the plot of a thriller, that’s because it’s the set-up of the new and utterly riveting John le Carre novel, Our Kind of Traitor. The Russian gangster is Dima, whose fate we follow as a rogue unit in British intelligence seeks to reel the would-be defector in to safety on England’s shores.

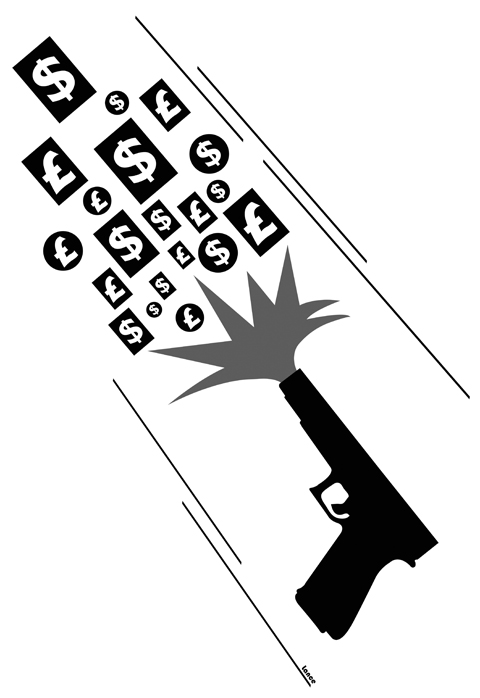

Now here’s another storyline. Leading banks around the world, desperate for cash in the financial crisis, turn to the proceeds of organized crime as “the only liquid investment capital” available, eventually absorbing the greater part of a staggering US$352 billion of drugs profits into the global economic system, laundering that vast sum in the process.

Sounds far-fetched, but that’s no fiction. That tale was published in the London Observer in December last year, when the head of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime admitted that colossal piles of drugs money had kept the world financial system afloat when it looked dangerously close to collapse.

The story broke long after Le Carre had finished Our Kind of Traitor, but it confirmed everything the new novel is saying: That a huge slice of the global economy, as much as a fifth on some estimates, is made up of the fruits of organized crime; that the criminals behind that money have found a thousand ingenious ways to disguise its origins — and those we might expect to stand in the way, including reputable banks and elected politicians, instead help smooth its path out of the black economy and into the white.

The problem is so vast, people somehow fail to see it.

“Nobody picked it up!” a still incredulous Le Carre said of that UN statement when we met in his Hampstead, north London, home on Tuesday. “I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but I really did have the feeling that it had been suppressed.”

He sees too many unanswered questions, starting with how exactly that US$352 billion came to pass into the legitimate economy.

“What buttons do you press, who do you call? Whose consent do you seek?” he asked.

Did someone in government wink to the super-crooks, telling them they no longer had to keep their money in cash in, say, the Cayman Islands, but could now buy government bonds? If so, who and on whose authority?

If this seems arcane, a matter for forensic accountants, it shouldn’t. French writer Balzac had it right: “Behind every great fortune, there lies a great crime.”

And behind today’s dazzling fortunes lie some very dirty crimes indeed: If it’s not selling guns or hooking the vulnerable on drugs, it’s trafficking young women as sex slaves and would-be economic migrants into servitude. When the profits of evil deeds like these are laundered, the world is saying that crime — even the gravest crime — does indeed pay.

The scale is enormous. The UK Serious Organised Crime Agency — SOCA — puts revenue from organized crime in the UK alone at £15 billion (US$ 23 billion) and admits that is likely to be a very conservative (and dated) estimate. Add in profits from Russia, India and beyond and the numbers reach the stratosphere.

None of that wealth would be much use to the gangsters if it stayed in telltale cash, betraying its tainted origins. So these real-life Dimas devise ever more ingenious ways to pass it off as legit. Property is a favorite: Buy a house, sell it on and the proceeds become clean. A department store works just as well, as does a soccer club.

Or create a series of shell companies registered behind a brass plate in faraway Vanuatu or the Solomon Islands, one owning another owning another, financial Russian dolls that “exhaust and bamboozle investigators,” according to Misha Glenny, whose book McMafia is the go-to guide to this new realm of international, multibillion-dollar crime.

He includes London in that roll call of safe havens, places attractive to those with illicit fortunes to bleach clean.

Once former British prime minister Gordon Brown set his heart on London outstripping New York as the world’s financial capital, Glenny argues, the inevitable result was lighter regulation, “no stress entry” for big fortunes, non-domicile arrangements to ease tax burdens and an entire legal architecture hospitable to the mega-wealthy.

That’s not to say the authorities are doing nothing. SOCA boasts of denying criminals assets of £317.5 million in the last year; but the words “drop” and “ocean” come to mind. Brown certainly tightened some rules in trying to crack down on terrorist finance after the Sept. 11 attacks, but, the experts agree, the regime still tends to catch the minnows while leaving the sharks to roam free.

As Hector Meredith, the principled spy in Our Kind of Traitor, puts it: “A chap’s laundering a couple of million? He’s a bloody crook. Call in the regulators, put him in irons. But a few billion? Now you’re talking. Billions are a statistic.”

What might explain the institutional blind eye turned towards these enormous, ill-gotten fortunes? Political influence. The Russian oligarchs, for example, have been tireless in their cultivation of political friends, sparing no expense.

Le Carre passes on speculation that there is a substantial body of peers sitting in the House of Lords “singing for the Russian choir.”

His novel features an ambitious British politician who mingles with high-rolling members of the Russian criminal fraternity on a yacht, though no doubt the resemblance to any real-life figure is purely coincidental.

And sometimes, in some places, it’s more than a blind eye. Glenny reports that in Italy following the financial crisis the mafia has been allowed to assume the role of the banks, lending at reasonable rates to small businesses. The mafiosi can do it because they are cash rich — and in return their money is washed clean. For organized crime, a recession is good for business.

What can be done? A kind of defeatism stalks Le Carre’s novel, as if this dragon is too powerful ever to be slain.

The author admits that he can’t see how any country can “get on terms with it.”

Others suggest action will be possible only when Russia — where the white and black economies are entangled in a permanent shade of dark gray — chooses to join the international struggle against organized crime.

However, there’s more that can be done now. The US has set a good lead, regarding any transaction done in dollars as within its jurisdiction (which is why the US authorities are pursuing the Saudi/BAE arms episode long after Serious Fraud Office investigators abandoned it in Britain). To go further, governments would have to find the political will to chase the big villains, not just the small ones. Ending the non-domicile regime would help too.

One reform is both surprising and easy. Oligarchs and their ilk don’t come to London for the weather: A big draw is our draconian libel laws, which keep them safe from scrutiny. Change those, so that at last we can start debating this enormous criminal racket out loud -- in the newspapers rather than on the pages of a novel, no matter how riveting.

Trying to force a partnership between Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and Intel Corp would be a wildly complex ordeal. Already, the reported request from the Trump administration for TSMC to take a controlling stake in Intel’s US factories is facing valid questions about feasibility from all sides. Washington would likely not support a foreign company operating Intel’s domestic factories, Reuters reported — just look at how that is going over in the steel sector. Meanwhile, many in Taiwan are concerned about the company being forced to transfer its bleeding-edge tech capabilities and give up its strategic advantage. This is especially

US President Donald Trump’s second administration has gotten off to a fast start with a blizzard of initiatives focused on domestic commitments made during his campaign. His tariff-based approach to re-ordering global trade in a manner more favorable to the United States appears to be in its infancy, but the significant scale and scope are undeniable. That said, while China looms largest on the list of national security challenges, to date we have heard little from the administration, bar the 10 percent tariffs directed at China, on specific priorities vis-a-vis China. The Congressional hearings for President Trump’s cabinet have, so far,

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the