Like every Chinese child, Li Hanwei spent her schooldays memorizing thousands of the intricate characters that make up the Chinese writing system.

Yet aged just 21 and now a university student in Hong Kong, Li already finds that when she picks up a pen to write, the characters for words as simple as “embarrassed” have slipped from her mind.

“I can remember the shape, but I can’t remember the strokes that you need to write it,” she said. “It’s a bit of a problem.”

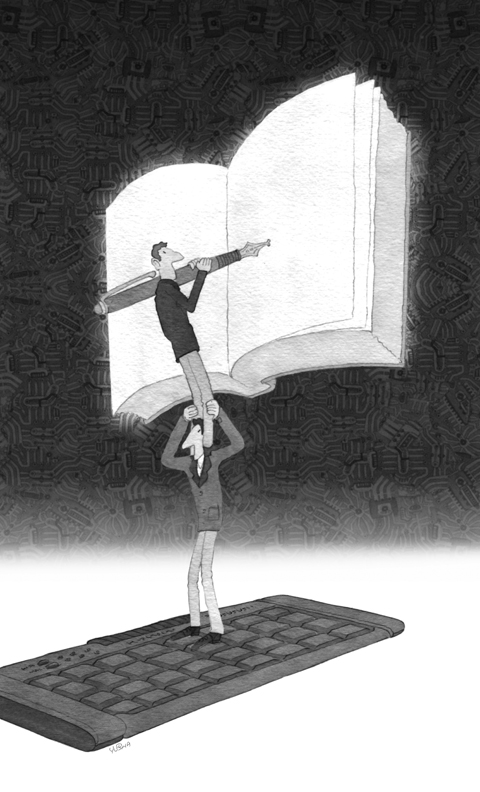

Surveys indicate the phenomenon, dubbed “character amnesia,” is widespread across China, causing young Chinese to fear for the future of their ancient writing system.

Young Japanese people also report the problem, which is caused by the constant use of computers and mobile phones with alphabet-based input systems.

There is even a Chinese word for it: tibiwangzi (提筆忘字) or “take pen, forget character.”

A poll commissioned by the China Youth Daily in April found that 83 percent of the 2,072 respondents admitted having problems writing characters.

As a result, Li says she has become almost dependent on her telephone.

“When I can’t remember, I will take out my cellphone and find it [the character] and then copy it down,” she said.

“I think it’s a young people’s problem, or at least a computer users’ problem,” said Zeng Ming, 22, from Guangdong Province.

One notoriously forgettable character, Zeng says, is used in the word Tao Tie — a legendary Chinese monster that was so greedy it ate itself.

Still used as a byword for gluttony, the Tao Tie is one of many ancient Chinese concepts embedded in the language.

“It’s like you’re forgetting your culture,” Zeng says.

Character amnesia happens because most Chinese use electronic input systems based on pinyin, which translates Chinese characters into the Roman alphabet.

The user enters each word using pinyin, and the device offers a menu of characters that match. So users must recognize the character, but they don’t need to be able to write it. In Japan, where three writing systems are combined into one, mobiles and computers use the simpler hiragana and katakana scripts for inputting — meaning users may forget the kanji, a third strand of Japanese writing similar to Chinese characters.

“We rely too much on the conversion function on our phones and PCs,” said Ayumi Kawamoto, 23, shopping in Tokyo’s upscale Ginza district. “I’ve mostly forgotten characters I learned in middle and high school and I tend to forget the characters I only occasionally use.”

“I hardly hand-write anymore, which is the main reason why I have forgotten so many characters,” said Maya Kato, a 22-year-old Tokyo student.

“It is frustrating because I always almost remember the character, and lose it at the last minute. I forget if there was an extra line, or where the dot is supposed to go,” she said.

Character amnesia matters because memorization is so crucial to character-based written languages, says Siok Wai Ting, assistant professor of linguistics at Hong Kong University. Forgetting how to write could eventually affect reading ability.

“There is no way we can learn the writing systematically because the writing itself is not systematic — we have to memorize, we have to rote learn,” she said. “Through writing, we memorize the characters. Reading and writing are more closely connected in Chinese.”

Chinese reading even uses a different part of the brain from reading the Roman alphabet, Siok’s research has found — a part closer to the motor area, which is used for handwriting.

Chinese characters are so complex that the country’s revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東) told the US journalist Edgar Snow in 1936: “Sooner or later, we believe, we will have to abandon characters altogether if we are to create a new social culture in which the masses fully participate.”

Instead, Mao eventually chose to simplify many characters into forms that are now the standard in mainland China.

Victor Mair, professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, said character amnesia is part of a “natural process of evolution.”

“The reasons why characters are innately difficult to enter into computers and mobile phones are innate to the character-based writing systems themselves,” he said.

“There are no magic bullets that will make it easy to input characters,” he said.

The Wubi input system — available on some Chinese computers and backed by the government — uses character strokes as handwriting does. But the system itself is so difficult to learn that it has failed to gain mass appeal.

However, iPhones and other smartphones now offer an option in which users can input characters by drawing them onto the touch screen.

And in Japan, kanji kentei — a character quiz with 12 levels — has become a widespread craze among schoolchildren, housewives and retirees, said Yoshiko Nakano, associate professor of Japanese at the University of Hong Kong.

Some argue that the perceived decline in character knowledge is, in fact, nothing to worry about.

A survey by the southern Chinese news portal Dayang Net, found that 80 percent of respondents had forgotten how to write some characters, but 43 percent said they used handwritten characters only for signatures and forms.

“The idea that China is a country full of people who write beautiful, fluid literature in characters without a second thought is a romantic fantasy,” blogger and translator C. Custer wrote on his Chinageeks blog. “Given the social and financial pressures that exist for most people in China ... [and] given that nearly everyone has a cellphone, it really isn’t a problem at all.”

The explosion of Internet and phone technology has itself led to the creation of new words and forms of writing. In 2008 Chinese were sending 175 billion text messages each quarter, Xinhua news agency said.

Still, both Li and Zeng have become so concerned about character amnesia that they keep handwritten diaries partly to ensure they don’t forget how to write.

If it weren’t for this, would they actually need to remember how to write characters with a pen?

Li is almost stumped, but says she uses one “when I have to sign the back of my new credit card.”

“That’s almost all,” she said.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not