The headquarters of probably the most powerful charity in the world, and one of the most quietly influential international organizations of any sort, currently stand between a derelict restaurant and a row of elderly car repair businesses. Gentrification has yet to fully colonize this section of the Seattle waterfront, and even the actual premises of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which, appropriately perhaps, used to be a check-processing plant, retain a certain workaday drabness. Only four stories high, with long rows of windows but no hint of corporate gloss, its beige and gray box sits anonymously in the drizzly northern Pacific light.

There is no sign outside the building. There is not even an entrance from the street. Instead, visitors must take a side road, stop at a separate gatehouse, also unmarked, and introduce themselves to a security guard, of the eerily polite and low-key kind employed by former heads of state and the extremely rich.

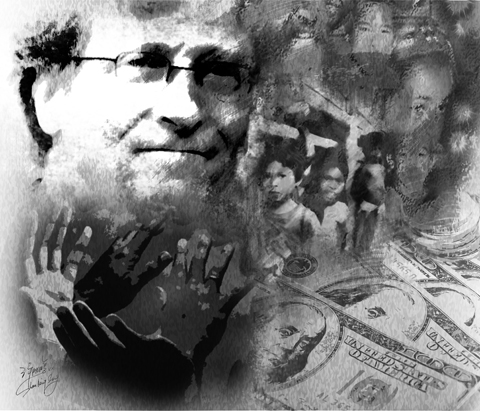

Once admitted, you cross a car park full of modest vehicles and, if you are lucky, glimpse one of the world-renowned health or poverty specialists working for the foundation, dressed in the confidently casual Seattle office uniform of chinos and waterproofs. Then you reach the reception: finally, there is a small foundation logo on the wall, and beside it a few lyrical photographs of children and farmers in much dustier and less prosperous places than Seattle. Only past the reception, almost hidden away on a landing, is there a reminder of the foundation’s status and contacts: a vivid shirt in a glass case, presented during a visit by former South African president Nelson Mandela.

The low-lit corridors beyond have little of the scruffiness and bustle you often find at charities. The fast-expanding foundation staff (presently around 850 employees) are in increasing demand around the world: meeting governments, attending summits and conferences and, above all, “in the field,” as foundation people put it, checking on the progress of the hundreds of projects — from drought-tolerant seeds to malaria vaccines to telephone banking for the developing world — to which the organization has given grants since it was founded in 1994.

In Seattle, maps of Africa and southern Asia, the foundation’s main areas of activity outside the US, are pinned up in the often empty, sparsely decorated offices and cubicles. There are also cuttings about the foundation’s work from the Economist and the Wall Street Journal, not publications you might have previously associated with a big interest in global disease and poverty. And lying on the foundation’s standard-issue, utilitarian desks, there are its confidently written and comprehensively illustrated reports: Ghana: An Overall Success Story is the title of one left in the unoccupied office I have been lent between interviews.

The foundation, in short, feels like a combination of a leftish think tank, an elite management consultancy and a hastily expanding Internet start-up. Is it the sort of institution that can really help the world’s poorest people?

For 14 of the last 16 years Bill Gates has been the richest person on Earth. More than a decade ago, he decided to start handing over the “large majority” of his wealth — currently more than US$54 billion — for the foundation to distribute, so that “the people with the most urgent needs and the fewest champions” in the world, as he and his wife Melinda put it on the foundation Web site, “grow up healthier, get a better education, and gain the power to lift themselves out of poverty.”

In 2006, Warren Buffett, currently the third richest person in the world, announced that he too would give a large proportion of his assets to the foundation. Its latest accounts show an endowment of US$36 billion, making it the world’s largest private foundation. It is committed to spending the entire endowment within 50 years of Bill and Melinda Gates’ deaths. Last year it awarded grants totaling US$3 billion.

As well as its money, it is the organization’s optimism and the fame of its main funder — in 2008 Bill Gates stopped working full-time for his computer giant Microsoft to concentrate on the foundation — that has given it momentum. In May of last year, an editorial in the revered medical journal the Lancet praised it for giving “a massive boost to global health funding ... The Foundation has challenged the world to think big and to be more ambitious about what can be done to save lives in low-income settings. The Foundation has added renewed dynamism, credibility, and attractiveness to global health [as a cause].”

Precise effects of big charity projects can be hard to measure, especially over a relatively short period. However, already two bodies that the foundation funds heavily, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) and the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, have, according to the foundation, delivered vaccines to more than 250 million children in poor countries and prevented more than an estimated 5 million deaths.

“The foundation has brought a new vigor,” says Michael Edwards, a veteran charity commentator and usually a critic of billionaire philanthropists. “The charity sector can almost disempower itself; be too gloomy about things ... Gates offers more of a positive story. He is a role model for other philanthropists, and he is the biggest.”

“Everyone follows the Gates foundation’s lead,” says someone at a longer-established charity who prefers not to be named. “It feels like they’re everywhere. Every conference I go to, they’re there. Every study that comes out, they’re part of. They have the ear of any [national] leadership they want to speak to. Politicians attach themselves to Gates to get PR. Everyone loves to have a meeting with Gates. No institution would refuse.”

The foundation has branch offices in Washington, New Delhi and Beijing. This year, it opened an office in London, not in one of the scruffy inner suburbs usually inhabited by charities, but close to the Houses of Parliament.

Head of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative [IAVI], Seth Berkley says: “The foundation has the advantage of speed and flexibility. When they want to, they can move quickly, unlike many other large bureaucracies. Most of the other private foundations in the US don’t work globally. Others are more staid than Gates. I used to work at the Rockefeller Foundation and dole out grants in small amounts. The Gates foundation gave us at IAVI a grant of US$1.5 million, then US$25 million. Then they gave us a line of credit — which is extremely unusual in grant-making — of US$100 million, to give us assets to be able to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies and initiate vaccine development programs. Using that US$100 million, we were able to leverage lots more funding — US$800 million in total. What Gates allowed us to do was go out and search for new ideas and move quickly on them. The old way was to find the new ideas, and then look for a donor to back them.”

Besides its dizzying grants, the foundation is also becoming a magnet for talented staff and collaborators.

“We probably get more than our fair share of great external expertise and insight,” foundation chief executive Jeff Raikes says.

Foundation staff can have a certain self-assurance. When the history of global health is written, says Katherine Kreiss, who joined from the US Foreign Service in 2002 and now oversees the foundation’s nutrition projects, “the start of the Gates foundation will absolutely be a seminal moment.”

Some have reservations about this power and the use made of it. Mindful of the foundation’s ubiquity, few in the charity world are prepared to criticize it on the record. However, in May last year the Lancet published two authored articles on the foundation.

“Grant-making by the Gates foundation,” concluded one article, “seems to be largely managed through an informal system of personal networks and relationships rather than by a more transparent process based on independent and technical peer review.”

The other article said that, “The research funding of the Foundation is heavily weighted towards the development of new vaccines and drugs, much of it high risk and even if successful likely to take at least the 20 years which Gates has targeted for halving child mortality.”

In a forthcoming article for the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, Devi Sridhar, a global health specialist at Oxford University, describes as a “particularly serious problem” the “loss of health workers from the public sector to better funded [non-governmental organizations] offering better remuneration.”

She also suggests that the foundation, like other health organizations based in rich countries but, active in the poor southern hemisphere, “[has] tended to fund ... a large and costly global health bureaucracy and technocracy based in the north.”

“Much of our grant-making goes to large intermediary partners that in turn provide funding and support to those doing the work in the field, often to developing country institutions. We’re not able to provide a simple funding breakdown,” the Gates foundation responded.

The rise of the foundation has been part of a larger revival of interest in the West in the problems of poor countries. This phenomenon has encompassed increased government aid budgets, initiatives by the WHO and World Bank, celebrity-led events and campaigns such as Live8, image-conscious corporate schemes, and countless private ventures, from the sober and long-term to the reactive, adventure-seeking, self-styled “extreme humanitarianism” currently being practiced in Haiti by freelance US volunteers and breathlessly described in the July issue of Vanity Fair.

It is hard to see this explosion of activity as a wholly bad thing. Though it does have political implications.

“It’s kind of [creating] a post-UN world,” says someone close to the Gates foundation. “People have gotten interested in fast results.”

The UN, he says, is too slow and bureaucratic — you could say democratic — to achieve them. Critics of the new, more entrepreneurial aid industry, such as the Dutch journalist Linda Polman, in her recent book War Games: The Story of Aid and War in Modern Times, see empire-building and wasteful competition as well as worthwhile altruism.

“Everyone in global health is talking about poor coordination,” says someone at a charity in that field. “The Gates foundation is contributing to the fragmentation and duplication.”

And finally, a suspicion lingers, slowly fading but still there, that the foundation’s activities are some sort of penance for Gates’ world-dominating behavior at Microsoft — or a continuation of that world domination by other means. Both Raikes and his predecessor as foundation chief executive were at Microsoft; Raikes from 1981 to 2008, during which time he was the company’s key figure after Gates and his co-founder Paul Allen.

As Raikes sits in his office, a little messy-haired, dressed in a zip-up jumper, fidgety in his chair and brisk in his answers, he even seems a bit like Gates.

“There are some real cultural differences between the Gates foundation and Microsoft,” he says. “Some of that’s good and some of that’s not so good. The foundation is in a stage of ... maturation. In philanthropy there is kind of a culture of, [he puts on a slightly airy-fairy voice] ‘You and I are here to help the world, and so we can’t disagree.’ At Microsoft, people would really throw themselves into the fray. I’m trying to encourage that here.”

He offers only limited reassurance to those who consider the foundation too powerful.

“We’re not replacing the UN,” he says. “But some people would say we’re a new form of multilateral organization.”

Is the foundation too ubiquitous?

“There are many people who want us to be much more involved than we want,” he said, smiling.

Since Raikes joined the foundation in 2008, it has nevertheless broadened its activities.

“Today we focus in on 25 key areas,” he says, then starts ticking them off on his strong fingers: “Eradicate malaria. Eradicate polio. Reduce the burden of HIV, tuberculosis, diarrhoea, pneumonia ...”

Why not concentrate on fewer of these huge tasks?

“You might say it’s a little bit of a business way of doing things. There are limits to the amount of money we could invest in any given area,” he said.

The foundation has so much money, it worries about saturating particular areas of need with grants and so achieving diminishing returns.

Instead, Raikes says, “We think dollars-per-DALY in a big way.”

DALY is an acronym for disability-adjusted life year, an increasingly common term in international aid and global health circles, which measures the number of years of healthy life lost to either severe illness or disability or premature death in a given population. The idea that suffering and its alleviation can be measured with some precision is characteristic of the foundation’s technocratic, optimistic thinking.

The charity also seeks to maximize its impact though partnerships. It does not, for example, conduct medical research or distribute vaccines itself; instead it gives grants to those it considers the best specialists.

“We think of ourselves as catalytic philanthropists,” Raikes says.

He confirms the widely held view — sometimes meant as a criticism — that the health solutions the foundation favors are usually technical.

“The foundation is really oriented towards the science and technology way of thinking. We’re not really the organization that’s involved in bed-nets for malaria. We’re much more involved in finding a vaccine,” he said.

The foundation’s health strategy is undergoing an internal review led by Girindre Beeharry, a pin-sharp youngish man from Mauritius who studied economics at the Sorbonne and Oxford.

“The iconic story we all tell about the foundation,” he says, “is, if you had been in polio [medicine] 50 years ago, and your only instrument [to combat it] had been the iron lung, the orthodox approach would have been, ‘How can we distribute iron lungs to Africa?’ Or you could have spent some of your dollars on developing a polio vaccine — which is how we think.”

Ignacio Mas, a fast-talking foundation man who did his economics at Harvard and specializes in financial services for the poor, adds: “If you have this mindset of finding big solutions for big problems, that means technology, in practical terms. Because that is really the only thing that can transform.”

Aware of how much they have already changed the world through their businesses, computer tycoons can turn into impatient broader reformers. Google co-founder Sergey Brin is currently funding an attempt to revolutionize the search for a cure for Parkinson’s disease.

Gates himself grew up in a charity-conscious environment: his mother, Mary, and his father, William Gates Sr, were both active in United Way, the international community service organization. The Gates family were prosperous, and lived in the hushed and idyllic suburb, but Seattle is an outward-looking, conscientious place: In the 1980s Mary led a successful campaign to persuade the local university to withdraw its investments from apartheid South Africa.

By the early 1990s, Bill Gates had started giving money to local schools and charities. However, the donations were small compared with the billions he was earning, and he was too focused on Microsoft to pay much attention to the growing number of begging letters that his wealth and fame attracted. His parents, privately, and Seattle journalists, publicly, began to suggest that he should be more civic-minded.

Then in 1995 he published The Road Ahead, a book he had co-written about the future of computing. Its sometimes bland corporate prose, Microsoft’s domineering reputation and Gates’ then unloved public persona meant that it received mixed reviews. Yet, read now, with the subsequent establishment of the foundation in mind, the book contains striking digressions about the world’s “sociological problems” and “the gap between the have and have-not nations.” There is a sense of Gates becoming curious about the world’s non-software needs and how he might help address them.

In 1994 he and his father had set up the William H Gates Foundation. Gates Sr ran it from his basement. Gates Jr wrote the checks. The causes he backed were broader than before: birth control and reproductive health. As the foundation expanded, he and Melinda, whom he had met at Microsoft, both found themselves becoming more and more interested in the wider world.

“I started to learn about poor countries and health, and got drawn in,” Bill Gates told students during a speaking tour this spring. “I saw the childhood death statistics. I said, ‘Boy, is this terrible!’”

He has a tendency to talk about the horrors and injustices of the developing world just as he talks about the computer business: in blunt, jerky sentences, his nasal voice flat or leaping, his manner without much natural warmth or charm. He sounds like a clever man in a hurry thinking out loud — which is exactly what he is. Starting in the late 1990s, he began to hungrily chew through the expert literature on global disease and nutrition and poverty.

“He is a giant sponge,” says an epidemiologist who specializes in HIV. “I had dinner with him a couple of weeks ago. The man is extraordinary. I’ve been in the field 15 years, and his grasp of the technical details is just astounding. His weird brain allows him to ask questions.”

This is part one of a two-part article. Part two will run tomorrow.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion