Carefully, the Chinese ivory dealer pulled out an elephant tusk cloaked in bubble wrap and hidden in a bag of flour. Its price: US$17,000.

“Do you have any idea how many years I could get locked away in prison for having this?” said the dealer, a short man in his 40s, who gave his name as Chen.

A surge in demand for ivory in Asia is fueling an illicit trade in elephant tusks, especially from Africa. Over the past eight years, the price of ivory has gone up from about US$100 per kilogram to US$1,800, creating a lucrative black market.

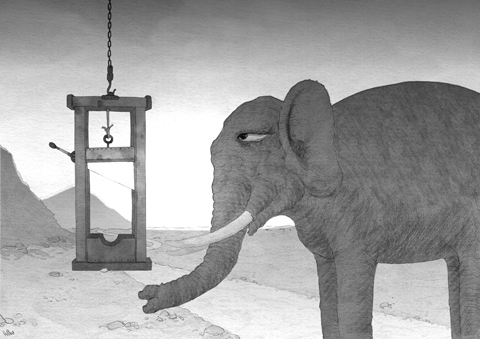

Experts warn that if the trade is not stopped, elephant populations could dramatically plummet. The elephants could be nearly extinct by 2020, some activists say. Sierra Leone lost its last elephants in December, and Senegal has fewer than 10 left.

“If we don’t get the illegal trade under control soon, elephants could be wiped out over much of Africa, making recovery next to impossible,” said Samuel Wasser, director of the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington. “The impact that loss of this keystone species would have on African ecosystems is difficult to even imagine.”

Wasser estimated that the illegal trade is about 100 times the legal trade, with a value of US$264 million over the past decade.

Demand for ivory runs strong in the Chinese city of Putian, which sits directly across from Taiwan, its outskirts crowded with factories owned by Taiwanese businessmen. These businessmen have a reputation for collecting ivory, a sure way to seal a deal with an important client.

Chen buys his ivory from middlemen. He said he doesn’t know its source.

“You don’t ask these questions,” he said.

Deep within the forests and parks of Africa, the source of ivory to China is clear.

In Kenya alone, poaching deaths spiked seven-fold in the last three years, culminating in 271 elephant killings last year. The Tsavo National Park area had 50,000 elephants in the 1960s; today, it has 11,000. And at least 10 Chinese nationals have been arrested at Kenya’s airport trying to transport ivory back to Asia since the beginning of last year.

The Kalashnikov assault rifles slung around the shoulders of Kenyan park rangers are not for animals, but for poachers. It is a dangerous game for both sides: A ranger was killed in a shootout on Christmas Day last year, and a poacher in a shootout in February.

Poachers use guns, rusty metal snares and poison arrows. It’s the poison arrows that worry the rangers because they belong to local Kenyan tribesmen. The pastoral tribes that once protected Kenya’s elephants are increasingly becoming their killers.

“Now the trend is different, because they know they can make quick money out of these trophies. They sell it to the poachers,” said Yussuf Adan, the senior warden in Tsavo East.

Such a sale can net a tribesman hundreds or even thousands of dollars, a life-changing amount.

Last month, ranger Mohamed Kamanya had to cut the tusks out of an elephant killed by a poacher’s poisoned arrow. Kamanya says it’s like a human death.

“Economic interests have surpassed ecological interests,” he said. “I think we’re in for a serious problem.”

The number of elephants in Africa has dropped by more than 600,000 in the last 40 years, mostly due to poaching.

A global ban on the ivory trade in 1989 briefly halted their demise. But the ban’s initial success has been undermined by a booming demand for ivory among Asian consumers, a decline in law enforcement budgets and a thriving black market that takes advantage of rampant corruption in many African countries.

Conservationists said poaching has steadily worsened since 2004 and now leads to the loss of as many as 60,000 elephants each year.

Compounding the problem has been the hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers who have migrated to Africa. Some buy up ivory in largely unregulated shops and join the criminal syndicates that smuggle the tusks back to Asia.

“What we found is that the illicit trade in ivory continues to increase and that it is increasing at a much more rapid rate than previously was the case,” said Tom Milliken, regional director for Traffic East Southern Africa, which analyzes ivory seizures.

Hidden in containers of mundane consumer products like cellphone parts, ivory is transported through as many as a half dozen countries between Africa and Asia to avoid detection. Shipping documents are forged, and the Asian gangs who control the trade often bribe customs officials to smooth the journey.

The gangs’ deep pockets have allowed them to smuggle much bigger shipments — often several tonnes at a time worth millions of US dollars, Milliken said.

Gangs are moving into the ivory trade because it is among the most lucrative enterprises, Wasser said.

“You can move huge amounts of contraband with low likelihood of getting caught,” Wasser said, noting that less than 1 percent of all containers are even searched. “The prosecutions are extremely low and fines even lower. That makes this high-profit, low-risk enterprise, which is conducive to the involvement of organized crime.”

Peter Younger, who manages a project that targets sub-Saharan Africa for the international law enforcement agency Interpol, said gangs also benefit from the fact that elephants are often living in countries like Somalia or the Democratic Republic of Congo, where law enforcement is nonexistent or preoccupied with keeping civil order.

“It’s easy to say to, for example, that Congo, you should do more to protect elephants, when they are doing everything to stop civil war,” he said.

The primary destinations for illegal ivory have traditionally been Thailand, Japan and China, which have thriving black markets and some of the world’s best ivory carvers. Thailand had three seizures last year and already had its biggest yet in February, when 2 tonnes of African tusks worth US$3.6 million were found in containers bound for Laos.

But these countries are not alone. Over the past decade, half of the largest ivory seizures took place in Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Vietnam, indicating they are also becoming key transit points, according to a report released in October last year by the Elephant Trade Information System.

Thailand and China best illustrate the challenges of stamping out the problem.

Thailand has been implicated in 59 seizures worldwide since 2007 as either a destination or transit point for ivory. A survey from TRAFFIC, a UK-based group that combats wildlife trafficking, last year found that hundreds of venues — from five-star hotels to the popular Chatuchak weekend market in the Bangkok — were selling tens of thousands of items made from ivory, from pricey carvings of religious deities to cheaper bangles, belt buckles and knife handles.

Police and customs officials acknowledge ivory smuggling is on the rise in the country. And while the government insists it is cracking down on the trade, officials admit corruption is rife within their ranks.

Lieutenant Colonel Adtapon Sudsai, who investigates the illegal trade, said it is not unusual to find ivory carvings in Buddhist temples or the homes of politicians or high-ranking police and military officers as a sign of power.

Investigations falter because local police are rarely trained to detect illegal ivory, Adtapon said. Prosecuting smugglers can also be difficult because traders often mix domestic ivory, which is legal, with the illegal African stocks.

Most shipping documents are forged or include a fake company or a nonexistent address. The person sent to pick up the shipment often knows nothing.

“We’re trying to get to those involved but we never have,” said Seree Thaijongrak, director of Investigation and Suppression Bureau in the Royal Customs Department.

Many countries, including Thailand, are now starting to track the ivory’s source through DNA testing. In making their first ivory arrests last year, Thai police used the testing to prove that ivory being sold by a Thai national to an US on e-Bay was in fact from Africa.

Zambia in 2002 claimed it had lost only 135 elephants over the past 10 years. But Wasser’s DNA testing showed it was closer to 6,000, which undercut the government’s argument that it should be allowed to sell its ivory stocks.

Wasser also said he used DNA testing to help determine where a shipment of 42,000 ivory signature seals confiscated in Singapore came from. The shipment had been tracked from Mozambique to South Africa, but DNA testing showed the ivory came from Zambia.

Such revelations helped kill a Zambian proposal at a UN conservation meeting in March that would have allowed a one-off sale of its 21,700kg of ivory. A similar proposal by Tanzania was also defeated.

“The dealers were getting purchase orders — I need so many tusks by a certain date,” Wasser said. “They were hammering the same areas over and over again. Law enforcement had no idea this was happening until we had shown the source of the Singapore seizure.”

Back in Putian, Chen shows how difficult it is to control the ivory trade.

Chinese police started cracking down on ivory theft in February.

Since the raids, Chen said he has stopped selling the xiang ya, the Chinese word for ivory, which translates to “elephant tooth.”

But not for long.

“I don’t dare sell anything now because they’re cracking down,” he said, over the din of electric saws being used to carve wooden dragon statues. “Come back in early June and I should be able to sell.”

Jason Straziuso reported from Tsavo East National Park in Kenya. Michael Casey reported from Bangkok and Bill Foreman reported from Putian.

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals