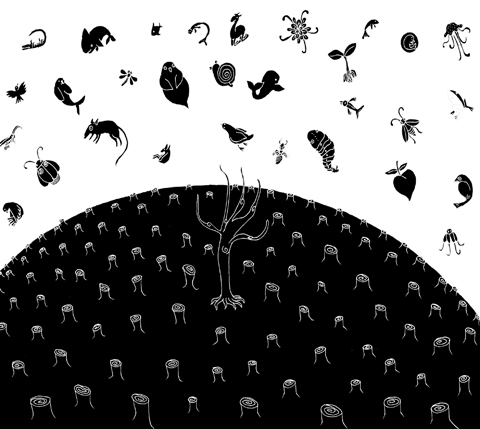

For the first time since the dinosaurs disappeared, animals and plants are being driven to extinction faster than new species can evolve, one of the world’s experts on biodiversity has warned.

Conservation experts have already signaled that the world is in the grip of the “sixth great extinction” of species, driven by humans’ destruction of natural habitats, hunting, the spread of alien predators and disease, and climate change. However, until recently it had been hoped that the rate at which new species were evolving could keep pace with the loss of diversity.

Speaking before two reports this week on the state of wildlife in Britain and Europe, Simon Stuart, chair of the Species Survival Commission for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) — the body that officially declares species threatened or extinct — said that that point had now almost certainly been crossed.

“Measuring the rate at which new species evolve is difficult, but there’s no question that the current extinction rates are faster than that; I think it’s inevitable,” Stuart said.

The IUCN created shock-waves with a major assessment of the world’s biodiversity in 2004 which calculated the rate of extinction had reached 100 to 1,000 times that suggested by fossil records before humans. No formal calculations have been published since, but conservationists agree the rate of loss has increased, and Stuart said it was possible the dramatic predictions of experts such as the Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, that the rate of loss could reach 10,000 times the background rate in two decades, could be correct.

“All the evidence is he’s right,” Stuart said. “Some people claim it already is that ... things can only have deteriorated because of the drivers of the losses, such as habitat loss and climate change, all getting worse. But we haven’t measured extinction rates again since 2004, and because our current estimates contain a tenfold range there has to be a very big deterioration or improvement to pick up a change.”

Extinction is part of the evolution of life, and only 2 percent to 4 percent of the species that have ever lived on Earth are thought to be alive today. However, fossil records suggest that for most of the planet’s 3.5 billion-year history the rate of loss may have been about one in every million species each year.

Only 869 extinctions have been formally recorded since 1500, because scientists have described fewer than 2 million of an estimated 5 million to 30 million species around the world, and assessed the conservation status of only 3 percent of those. The global extinction rate is extrapolated from the rate among known species. In this way the IUCN calculated in 2004 that the loss had risen to 100 to 1,000 per million species each year, a situation comparable to the five previous mass extinctions — the last of which was when the dinosaurs were wiped out about 65 million years ago.

Critics, including the author of The Skeptical Environmentalist, Bjorn Lomborg, have argued that because such figures rely on so many estimates, the margins of error make them unreliable.

However, Stuart said that the IUCN figure was likely to be an underestimate of the problem, because scientists are reluctant to declare species extinct even when they have sometimes not been seen for decades, and because few of the world’s plants, fungi and invertebrates have yet been formally recorded and assessed.

Swedish scientists had already warned that anything over 10 times the background rate of extinction — 10 species in every million per year — was above the limit if the world was to be safe for humans, said Stuart.

“No one’s claiming it’s as small as 10 times,” he said. “The only thing we’re certain about is the extent is way beyond what’s natural and it’s getting worse.”

Many more species are discovered every year around the world than are recorded extinct, but these “new” plants and animals are existing species found by humans for the first time.

In addition to extinctions, the IUCN has listed 208 species as “possibly extinct.” Nearly 17,300 species are considered under threat. These include one in five mammals assessed, one in eight birds, one in three amphibians, and one in four corals.

Later this year the Convention on Biological Diversity is expected to formally declare that a pledge by world leaders in 2002 to reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010 has not been met, and to agree on new, stronger targets.

Experts stress that understanding of factors that drive plants and animals to extinction has improved greatly, and targeted conservation can be successful in saving species from extinction in the wild.

This year has been declared the international year of biodiversity. It is also hoped that a major UN report this summer on the economics of ecosystems and biodiversity will encourage governments to devote more funds to conservation.

Norman MacLeod, keeper of palaeontology at the Natural History Museum in London, cautioned that when fossil experts find evidence of a great extinction it can appear in a layer of rock covering perhaps 10,000 years, so they cannot say for sure whether there was a sudden crisis or a build-up of extinction rates over centuries or millenniums.

“If things aren’t falling dead at your feet, that doesn’t mean you’re not in the middle of a big extinction event,” he said. “By the same token, if the extinctions are and remain relatively modest, then the changes, [even] aggregated over many years, are still going to end up a relatively modest extinction event.”

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.

Taiwan-India relations appear to have been put on the back burner this year, including on Taiwan’s side. Geopolitical pressures have compelled both countries to recalibrate their priorities, even as their core security challenges remain unchanged. However, what is striking is the visible decline in the attention India once received from Taiwan. The absence of the annual Diwali celebrations for the Indian community and the lack of a commemoration marking the 30-year anniversary of the representative offices, the India Taipei Association and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Center, speak volumes and raise serious questions about whether Taiwan still has a coherent India