When Patrick Giger, a 34-year-old angler from the Swiss village of Horgen, cast his baited line into Lake Zurich’s storm-swollen waters on an icy February morning last year, he could not have forecast the trouble he would end up reeling in alongside the 10kg pike that was soon to snare itself on his hook. The day ended with the monster fish being devoured by Giger and his friends at a local restaurant, but just a few months later Giger would face, on the instructions of the state prosecutor for the canton of Zurich, criminal prosecution for causing excessive suffering to the animal after boasting to a local newspaper that he had spent about 10 minutes, and exerted considerable physical effort, landing the fish.

The pike has gone on to become something of a poster child for the animal rights movement in Switzerland. It has even attracted more than 6,000 “fans” on a Facebook page set up in its memory. The fate of this fish, however, also acts to highlight the political divisions in Switzerland over just how far to push its animal rights legislation, already hailed as arguably the toughest anywhere in the world. The ultimate test came on Sunday when the country decided in a referendum — or “people’s initiative” — against an animal being represented by a lawyer during any criminal trial in which it is judged to be the “victim.” The canton of Zurich has had just such a lawyer — or “animal advocate,” as the incumbent prefers to be called — since 1991, but the campaigners who garnered the 100,000 signatures required to automatically trigger a national referendum hoped animal advocates would be required by law in all 26 cantons.

Antoine Goetschel, Zurich’s animal advocate since 2007, acted in court on behalf of the pike two weeks ago when Giger’s trial finally came before a judge. Giger was acquitted, but Goetschel is still hopeful that when the judge finally submits his written summary of the trial in the coming weeks, he will clarify what time-length is acceptable for a fisherman to land a fish.

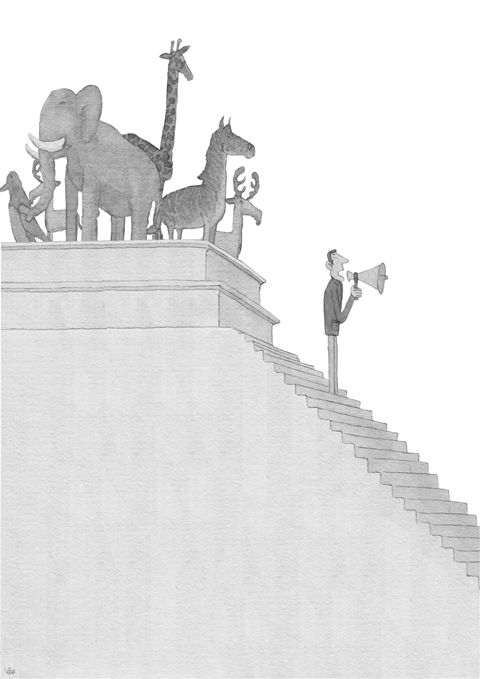

For some in Switzerland, the apparent absurdity of a dead fish having its own legal counsel — let alone placing such a legal time limit on anglers — displays that the animal rights agenda has now gone too far. However, supporters of the referendum argue that this strikes at the very ethical and philosophical heart of animal rights: Why shouldn’t an animal, they argue, have the same legal right to representation as any other victim in a criminal trial? When you open that particular Pandora’s box, a whole slew of other chewy questions follow. For example, do all animal species deserve equal rights? If an elephant deserves a lawyer, what about that defenseless slug squished underfoot by a vengeful gardener? Such questions have been troubling moral philosophers for centuries, but it could soon have a practical application in all of Switzerland’s criminal courts.

“Are fish sentient beings or not?” asks Goetschel rhetorically, as he thumbs the shelves of his law firm’s library, located in downtown Zurich not much more than a fly cast away from the lake where his client once swam.

“This is the sort of question I am asked to consider in such cases. This fisherman was boasting that it took him around 10 minutes to bring in the pike. The state attorney asked me to look into it. This is my job. I found a case judgment in Germany that said anything over one minute is too long so I used this as evidence. It was uncomfortable in the court as I had 40 fishermen against me. But I ask you this: If we put a hook in the mouth of a puppy and did the same thing for 10 minutes, what would our reaction be? With farm animals there is a strict, legally enforceable time limit between capture and death, so why not with fishing?” he said.

Goetschel rejects his critics who claim this all amounts to yet another money-spinner for lawyers. He said he handled 150 to 200 animal cases a year which, in total, take up about a third of his time.

“I get paid 200 [Swiss] francs [US$187] an hour for representing animals, but the fee for my other work is 350-500 francs per hour so I don’t do this for the money,” he said. “In 2009, I received 78,000 francs in total — just enough to pay for half an assistant at my office.”

So who does pay for his time? Clearly not the pike and all the other animal victims he represents in court.

“I’m designated by the canton government to do this job for four years,” he said. “The state pays me, otherwise it would be seen that I’m too close to being a representative of an animal rights NGO [non-governmental organization]. For me it is about conviction rather than money. It’s a thrill for me to make the public think about the animal/human relationship.”

There is a core principle of fair justice that underpins his work, he said. Animals can be, and often are, treated poorly by their human masters. However, while this person can defend themselves, the animal cannot.

“Not even a vet can act on behalf of the animal in court,” he said.

In late 2008, a new animal act passed into law in Switzerland. It runs to 150 pages and explains in great detail how dozens of species are to be kept and treated by their owners, be they “companion animals” or livestock on a farm. In November, the law will finally become legally enforceable, meaning the owner of, say, a rabbit could be prosecuted for keeping their pet in a hutch that doesn’t meet the legal criteria.

A dwarf rabbit, for example, must be kept in a hutch no smaller than 50cm x 70cm, with 40cm headroom. They must also have a nest box, or the “ability to dig.” (Curiously, gerbils are accorded more head room than rabbits.) The new rules for dogs are even more exacting. Dogs are deemed “social animals” and, therefore, “must have daily contact with humans, and, as far as possible, with other dogs.” If kept in outdoor kennels, they must be “chain free” for at least five hours a day and kept in pairs, or with other “compatible animals.” It said they must be walked daily, but the act fails to specify for how long or how far (which has angered some campaigners). And all prospective owners must now complete a four-hour “theory” course before buying a dog then complete a further four hours at a dog school as soon as they take ownership of the animal. Dogs must only be fed “species specific” food and their “enclosures” must have separate areas for eating, sleeping and toileting. If only half the world’s human population could be given such guarantees, sniff the critics of the animal act.

“The 2008 law was good for animal protection,” said Goetschel, who can even represent the best interests of a pet in any custody battles resulting from a (human) divorce. “I think the fight about the level of protection is now probably over in Switzerland. We have the ‘dignity of the animal’ recognized in Swiss law. But there is a struggle between the idealism of the ethics and the realism of the application of the law. Ethics should be there like a lighthouse to show where to go. Our high rates of prosecution in the canton of Zurich where we have an animal advocate, compared to the others, shows why someone such as me is needed. The mentality of the police and state attorneys varies from canton to canton. They have murders and drugs to deal with, so animal cases are often a low priority. They also have a lack of knowledge about the new law. The whole of Switzerland would probably need about six to 15 attorneys to cover all the animal cases arising each year.”

Goetschel, a vegetarian without pets who accepts the “hypocrisy of wearing leather shoes and silk ties,” gets far more animated when moving on to the deeper questions about our attitude toward the animals we keep.

“The 2008 law only protects vertebrates,” he said. “Invertebrates are deemed not to suffer pain so were left out. Five classes are covered by the law: birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals and fish. This only accounts for 5 percent of the animal world. But securing the ‘dignity of plants’ has now even been discussed. It can all lead to some interesting dilemmas. For example, what about the scientist who is trying to make a flea with 12 eyes? Who is representing the dignity of this creature?”

So should all forms of life on this planet have rights enshrined in law?

“I happen to believe that invertebrates are more or less equal to vertebrates. This thinking isn’t new. In the 19th century, a man in the UK was prosecuted for leaving his scorpions to die. It was the UK in 1822 who introduced the world’s first animal welfare law with the Act to Prevent the Cruel and Improper Treatment of Cattle. It was Jeremy Bentham’s thinking that invertebrates should have common value to other animals and I share this view. Snails and fleas are used in lab experiments; they should have some form of representation. It’s the principle of their use that is important to me rather than the individual animals themselves. I believe that we increase our own dignity when we increase the dignity of others,” he said.

Goetschel accepts that the pike was one of his more unusual clients. The species he represents the most are, in order, dogs, cows, cats and pigs. However, he is ever wary of what he calls the “puppy trap.”

“There is a danger that we only try to protect the animals we think are cute,” he said. “I must strip myself of emotion. How would you choose to prosecute the person who cut the head off a cat with a knife versus the person who didn’t give any food and water to their cat for two weeks causing it to die? Which cat suffered more? Suffering and dignity should be what guide you, not emotions.”

The role of organizations such as the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA) is important, he said, but an extra level of protection is required in his view.

“The RSPCA in the UK can act as ‘non-instructed policemen,’” he said. “But the RSPCA does not have the legal right to represent the animal in court. I can ask a question to a witness. I can make an appeal. My position can be very useful. For example, I represented 70 dogs that had been mistreated by their owner. The state attorney asked if I wanted to write up all their cases individually. But I said, let’s just pick three representative dogs and we were able to do a plea bargain as a result. Without me, this case could have potentially taken a year.”

Before Sunday’s referendum, Goetschel admitted to being nervous about the result. It was too close to call, he said. But would he like to see other countries following Switzerland’s lead?

“The Swiss have made steps that would be nice to see implemented in other countries — the French, for example, say the keeping of an animal is a basic human right — but I’m not proud of Switzerland just yet,” he said.

Peter Singer, the professor of bioethics at Princeton University and author of Animal Liberation, the book many credit with kick-starting the modern animal rights movement in the 1970s, said he was thrilled that the Swiss were voting to take what he sawas such a progressive step.

“I have always argued that it should be possible for animals to be represented in court by guardians, or lawyers, acting on their behalf, much as we do for people with disabilities,” he said.

It is a positive move toward what he would describe as his dream scenario: “Ideally, you would have laws requiring that we give equal considering to an animal’s interests where their interests are similar to ours, that we do not discount their interests merely because they are not human. The details are going to vary according to the species and according to why the animal is being kept. You’re either going to have very complicated legislation, or you’re going to have procedures that set up committees and tribunals in order to decide what is the proper way to keep animals which will range across the species. But if you’re talking about a perfect world, we’re not there yet. Are we going to cease using animals for food, for example? That’s not an issue that’s up for vote in the Swiss referendum. They’re not going to stop making their cheese.”

Polling before the referendum indicated that the “Yes” campaigners could achieve 70 percent of the popular vote, but over the week before Sunday, the “No” campaign leaders called for a letter-writing campaign to newspapers — a strong political tradition in Switzerland — and the pages were filled with dissenting views about the need for animal advocates across the country.

“Let me say straight away that I support our 2008 animal protection laws,” said Hannes Germann, a senator for the canton of Schaffhausen and prominent member of the Swiss People’s party, the rightwing party that successfully campaigned last year for a building ban on minarets in Switzerland. “But it is enough. If you ask people what is important for this country at this time, it is not yet more bureaucracy and the needless spending of tax-payers’ money. We have bigger issues to fight than this.”

The “Yes” campaigners rejected the idea that animal advocates were a luxury. Eva Waiblinger, a zoologist who works as the “companion animal welfare specialist” for the animal rights group Schweizer Tierschutz (Swiss Animal Protection), said Goetschel only costs each taxpayer in Zurich canton SF0.08 a year. She said she was hopeful, but nervous about the referendum. (The result did not hinge on the national popular vote, but whether a majority of cantons supported the initiative. It was this that campaigners on both sides said was on a knife-edge.)

“Anglers and farmers are against us,” she said. “But the Swiss Kennel Club is supporting us, as are most of the newspapers.”

The intention of animal advocates, she said, was simply to better enforce the 2008 animal welfare act. She was pleased with the new guarantees of protection — “If I was a chicken I’d want to live in Switzerland” — but thought they could have gone even further in places.

“There is a problem with species-ism in the act. It encourages what is in effect racism against certain species. That’s my problem with it all,” she said.

When viewed against the protection animals get in other countries, however, she said she was proud that Switzerland was the world leader in animal protection.

“When I came to London recently I was shocked to see puppies and kittens for sale in Harrods,” she said. “They even had plastic hamster balls which you can put on the floor and watch the hamster running inside as the ball rolls around. If I’d seen this in Switzerland, I would have gone to the police.”

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama