How to justify the ways of men to birds? How to account for their attraction for us? (For, despite Hitchcock’s frightening hunt-and-peck film, The Birds, it is mostly an attraction.) Why is Chekhov’s play called The Seagull instead of The Sea Slug? Why is Yeats so keen on swans and hawks, instead of an interesting centipede or snail, or even an attractive moth? Why is it a dead albatross that is hung around the Ancient Mariner’s neck as a symbol that he’s been a very bad mariner, instead of, for instance, a dead clam? Why do we so immediately identify with such feathered symbols? These are some of the questions that trouble my waking hours.

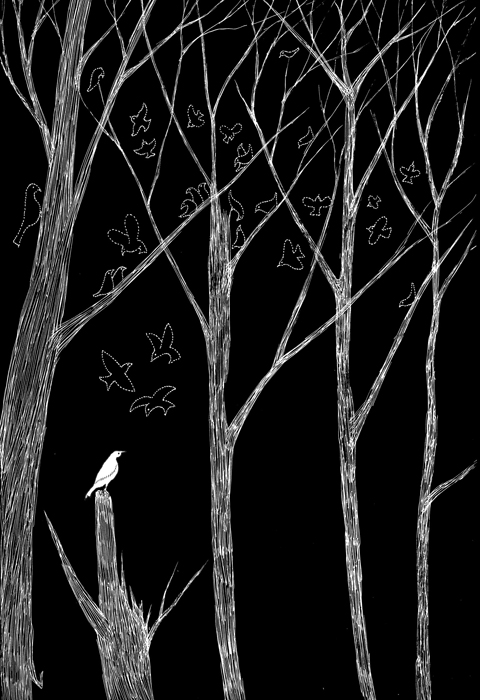

For as long as we human beings can remember, we’ve been looking up. Over our heads went the birds — free as we were not, singing as we tried to. We gave their wings to our deities, from Inanna to winged Hermes to the dove-shaped Holy Spirit of Christianity, and their songs to our angels. We believed the birds knew things we didn’t, and this made sense to us, because only they had access to the panoramic picture — the ground we walked on, but seen widely because seen from above, a vantage point we came to call “the bird’s eye view.” The Norse god Odin had two ravens called Thought and Memory, who flew around the Earth during the day and came back at evening to whisper into his ears everything they’d seen and heard; which was why — in the mode of governments with advanced snooping systems, or even of Google Earth — he was so very all-knowing.

Some of us once believed that the birds could carry messages, and that if only we had the skill we’d be able to decipher them. Wasn’t the invention of writing inspired, in China, by the flight of cranes? Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes credited with the invention of hieroglyphic writing, had the head of an ibis. In the ancient world, an entire job category grew up around bird reading: that of augury, performed by seers and prophets who could interpret the winged signs. When Agamemnon and Menelaus were setting out for Troy, two eagles tore apart a pregnant hare and ate the unborn young. The augur’s prediction was victory — Troy would fall — but an ill-omened victory with a heavy price to be paid; and so it turned out. “A bird of the air shall carry the voice,” says Ecclesiastes, with impressive gravitas, “and those that have wings shall tell the truth”; and we can bet that those bird-borne truths were momentous.

By the 1950s, when I was what’s now called a young adult, respect for birds had dwindled considerably. Birds might still be thought to carry messages — “a little bird told me,” we were fond of saying — but these messages were no longer from the gods, and they no longer concerned the deaths of kings and the fates of nations. They were more likely to be from the girl who had the locker next to yours, and to be about who just broke up with whom. “Bird-brained” meant stupid, and people with too obsessive a knowledge of birds were considered geeky and ridiculous. Bird-watching had become an increasingly popular pastime — a trend spurred by Roger Tory Peterson’s 1934 publication of the first Field Guide to the Birds — but one of the effects of this growing popularity was the appearance of parody versions of such guides, filled with cartoons of silly-looking people in pith helmets with names like “The Spectacled Drone,” who were watching girls in halter tops and short-shorts captioned “The Rosy-Breasted Nutcracker.” There were also various puns on the slang word “bird,” meaning either an attractive girl or — cf Frank Sinatra — the male genital organ. The supposed light-mindedness and frivolity of birdy activity is mirrored today in the name of the popular Twitter site, with “tweet” being the term for a tiny info-tidbit.

But times change, and we’re heading back toward an older way of reading the birds. It’s Fates of Nations time again, and ill omens seen through birds in flight — or the absence of them — and deadly prices to be paid for getting what you want. The birds have something to tell us again, and the truths are not comfortable ones.

I’ve always lived in the birdy world. I grew up in it — my parents were early conservationists and naturalists — and I can tell you from personal experience that small children have a limited tolerance for sitting still in canoes for hours on end being gnawed by mosquitoes, to see if the Very Rare Blur will deign to do a flit-by, when they won’t see it anyway because they were making the more controllable ant crawl up their arms. But early training does sometimes bear fruit, and I reconnected with the bird world once everyone, including me, realized that I was nearsighted. I needed special help with the twirly thing on the top of the binoculars, at which point the Very Rare Blur resolved into something I could actually see.

Birds of a feather flock together, so I eventually ended up with another bird-oriented person — Graeme Gibson, more recently the author of The Bedside Book of Birds and the chair of the board of the Pelee Island Bird Observatory. Sitting in a canoe being gnawed by mosquitoes while waiting for the Very Rare Blur is a lot better if you yourself are in charge of the timetable — as in, “Let’s have lunch now” — so we did a lot of birdwatching. Graeme had the zeal of a recent convert, I displayed the nonchalance of the born denominationalist, but our shared pursuit took us to many unusual places in the world. Some of our sightings were not heroic — the distant never-before-glimpsed-by-human-eye prehistoric Mexican enigma turned out to be a brown pelican, the snowy owl was actually a white plastic milk bottle — or was it the other way around?

Back in the 1970s and 1980s and then the 1990s, however, you could depend on the birds to be more or less where they were supposed to be, more or less when they were supposed to be there. Failures to see them were bad luck or lack of skill on your part: The birds themselves were surely just around the corner. If not this time, then next; if not this year, then next. But all that is changing, and it’s changing very rapidly. The suddenness of the decline — not only in threatened species, but in relatively abundant ones, such as the neotropical woodland warblers — is very worrying. No bird species can any longer be taken for granted.

In February 2006, Graeme and I accepted the position of joint honorary presidents of the Rare Bird Club within BirdLife International. BirdLife describes itself as “a global partnership of conservation organizations working for the diversity of life through the conservation of birds and their habitats.” Sometimes it subtitles itself “Working for birds and people.” Under that broad umbrella, it supports an impressive number of activities carried on by its country partners all around the world — everything from running a Preventing Extinctions program focused on birds at risk, to studying international migration flyways in order to remove thoughtlessly-built man-made hazards, to monitoring toxicity that kills birds fast and people more slowly. (A hint: If birds are dying in the water, don’t swim there.) BirdLife’s many projects are implemented on the ground through its country partners — over 100 of them, and growing — but the secretariat that does much of the science and manages the overall network is located in Cambridge, England, and it has the same problem all conservation organizations have: It’s easier to attract donations for individual projects than for overall management.

The Rare Bird Club’s task is to support the secretariat, and to fundraise for it. Graeme and I agreed to take this on, not because we had time on our hands — we didn’t — but because we knew about the crisis in the life of birds, and also about the connection between a healthy ecosystem and a healthy human population. “Canary in the coal mine” — which comes from a time when miners knew that if their caged canaries toppled over it meant imminent asphyxiation for them — is not an empty phrase: Where birds are dying now (through poisons, habitat destruction and famine), people will die later. The die-off in seabirds, for instance, signals a die-off in sea life, including fish. It doesn’t take a very smart augur to read that kind of bird omen.

Three snapshots: Two summers ago, we were with some Rare Bird Club members in the high Arctic. We were watching a polar bear finishing the remains of a seal, while nearby two all-white ivory gulls waited to pick over the bones. Everyone present knew that all the main elements of this scene — the feeding bear, the gull, the ice itself — might soon disappear from the Earth like a mirage, as if they had never been. This could happen, not in centuries, but in years. It’s was global warming, not as a theory, but in a very concrete form.

Much further south, on an island off the coast of Georgia, we stood on a beach and watched a large flock of red knots — named originally for King Canute — feeding along the surf line. They were busily at work there, but we knew that further up the coast people were “harvesting” the horseshoe crabs that spawn on the beach, thus eliminating the crab eggs the birds depend on to sustain them during their long migration.

Further south still, at the bottom of New Zealand’s South Island, we went out one night to see kiwis — those flightless balls of feathery fur with long curved bills we first met, as children, on tins of shoe polish. Sometimes not a single kiwi is sighted on such trips. But we were favored; we saw five: young, mature, male and female. None of these had fallen prey to those scourges of ground-dwelling New Zealand birds — the cats, the rats and the dogs — but many of their kindred had. All flightless and ground-nesting New Zealand birds are under threat. The carnage since the arrival of people on New Zealand has been brutal.

That’s the key: “Since the arrival of people.” Most of the time, we don’t kill birds on purpose. We kill them by accident, or at second-hand through our technologies, our pets, or our fellow-traveler pests.

Here are a few statistics. In the US, power lines kill 130 million to 174 million birds a year — many of them raptors such as hawks, or waterfowl, whose large wingspans can touch two hot wires at a time, resulting in electrocution, or who smash into the thin power lines without seeing them (think piano wire). Cars and trucks collide with and kill between 60 million and 80 million annually in the US, and tall buildings — especially those that leave their lights on all night — are a major hazard for migrating birds, leading to between 100 million and 1 billion bird deaths annually. Add in lighted communication towers, which also kill large numbers of bats and can account for as many as 30,000 bird deaths each on a bad night — thus 40 million to 50 million deaths a year, and due to double as more towers are built.

Agricultural pesticides directly kill 67 million birds per year, with many more deaths resulting from accumulated toxins that converge at the top of the food chain, and from starvation as the usual food of insectivores disappears. Cats polish off approximately 39 million birds in the state of Wisconsin alone; multiply that by the number of states in the US and then do the calculations for the rest of the world: The numbers are astronomical. Then there are the factory effluents, the oil spills and oil sands, the unknown chemical compounds we’re pouring into the mix. Nature is prolific, but at such high kill rates it’s not keeping up, and bird species — even formerly common ones — are plummeting all over the world.

One more statistic: According to former US vice president Al Gore, 97 percent of charitable giving goes to human causes. Of the remaining 3 percent, half goes to pets. That leaves 1.5 percent devoted to the rest of nature — including the crisis-ridden oceans, the eroding, drying or flooding land and the shrinking biosphere on which our lives depend. How crazy are we? We’re a lot like those old cartoons in which the foolish character is sawing off the same tree branch he’s sitting on, while beneath him is a sheer drop to nowhere. It makes you want to stick your head in the sand, like — apparently — almost everyone else and just eat a lot, watch old movies from the time before things got so scary and go shopping. Or, as James Lovelock keeps warning us: Enjoy it while you can, whatever “it” is, because it’s not going to last much longer.

Despite such gloom — or perhaps because of it — there are many intrepid individuals and organizations out there, hurling themselves on to the tracks in the path of the speeding EcoDeath Express. There are international organizations, national ones, local ones; all are understaffed and overworked, like hospitals during pandemics. As I’ve said, my own connections are with BirdLife International; I attended its international convention in Argentina last September. These conventions happen only every four years, and they bring together the representatives of BirdLife’s national partners from around the world. The energy and enthusiasm were contagious, and it was clear from just a few glances around that the days of the 1950s stereotype of the harmless, nerdy Spectacled Drone was gone forever.

Those now involved in bird conservation are serious and gutsy people — much more Seven Samurai than Jerry Lewis. They know their stuff, and the stuff they know can be pretty edgy. We heard tales of how the Ecuadorean organization Aves & Conservacion had fought illegal habitat destruction and tree piracy with online posts, and when these generated death threats, it had posted the threats as well, until it had finally forced its government to act; of how the Maltese partner, BirdLife Malta, had finally stopped the devastating, and — in the EU — illegal spring bird hunt on this key migration island with the help of the European Commission, which had taken the island to court. There were death threats involved in that action, too, and car bombings as well; but with the support of more than 70 percent of the island’s residents, the cause had finally been won. We heard about the compilation of the Guide to the Birds of Iraq, an enterprise that involved great danger for those doing the work. The conservation movement has its leaders and its foot soldiers, but also its martyrs: There have been human deaths as well as bird deaths.

A large part of BirdLife’s energies are directed toward mapping important bird areas and attempting to protect them, and in cataloging rare birds and monitoring them. In this way, rare and endangered birds that live in such areas and never leave them can be saved. But what about migrating birds? They run the gauntlet: If every stopping point but one is made safe, it’s the one unsafe point that will kill the species. This is where international networking can help.

Consider the albatross. Nineteen of the 22 albatross species — the literary bird whose corpse was hung around the neck of the Ancient Mariner “instead of the cross,” to symbolize a non-human sacrificial being — has been under threat for years from long-line and trawl fishing. The hooks — as many as 1,000 per line — are dragged along behind the boats, and the bait on them attracts fish, which in turn attract albatrosses, which then get snagged on the hooks. The fishermen don’t mean to catch the albatrosses; in fact, it’s a disadvantage to them. As for the albatross, the breeding cycle is very long and typically only one chick is reared at a time, so it’s been very easy to kill more birds than can be replaced by the species themselves. Before 2005, hundreds of thousands were dying annually. The albatross is a circumpolar bird, living mostly at sea, so trying to monitor it and help it cannot be the work of any one country.

In view of these difficulties, BirdLife established an international albatross task force in 2005 to work in seven countries, with a mandate to help both fishermen and birds. The task force placed specialized instructors on the fishing boats, to teach the simple, effective and money-saving solutions — mere changes in fishing techniques — to the fishermen themselves. The result has been that thousands of albatrosses are now being saved. For instance, in the south Chile seas, the accidental capture of seabirds has been reduced from 1,500 a year to zero, with a close to zero rate having been achieved in Argentina. Despite these gains, 100,000 albatrosses are still being killed in fisheries every year and 18 albatross species are facing extinction. But there’s a glimmer of hope: The task force has shown that with a lot of will and with ridiculously small amounts of money, the death trend can be turned around.

But it’s a matter of time, and extinction is forever. Human beings, it seems, are like little children, who never do quite believe that “all gone” means there isn’t any more, at all, ever.

Still, “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” wrote Emily Dickinson. Too often, these days, it isn’t. But in the case of the albatross, it is, if we’re reading the bird signals right. Or at least it could be, which is the nature of hope.

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals