A yachtsman friend of mine was sailing the blue waters of the Persian Gulf off the shimmering coast of Dubai recently when he came across a disturbing phenomenon: The World was dissolving before his eyes.

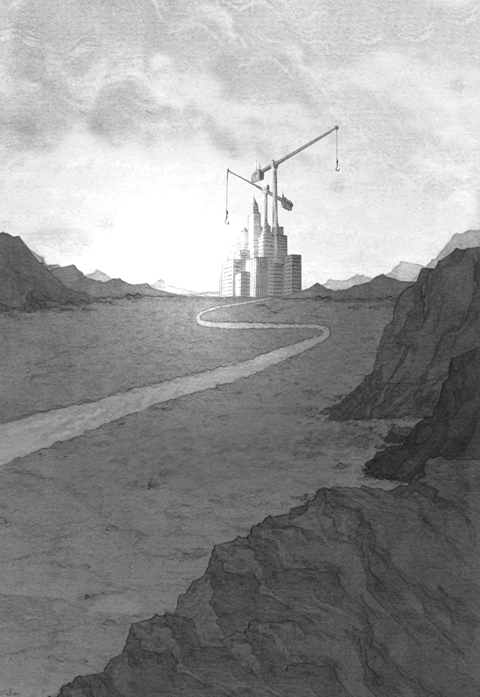

It was not the grog. Three years ago, when Dubai’s debt-fueled boom was at its height, the emirate launched its most ambitious project yet — a gigantic offshore replica of the planet Earth, made from sand dredged from the deserts and beaches of Arabia, with countries and continents carved out among a man-made archipelago of 300 islands. It was called simply The World.

Like most things in Dubai, it was for sale. Wealthy celebrities with US$20 million or so of loose change could buy Britain or France or Australia and erect their own secluded fun palace by the sea.

That project is unlikely ever to be completed. Work on it stopped earlier this year when the developer, Nakheel, ran out of money. Deprived of essential maintenance and reinforcement, the islands are slowly slipping back beneath the waves.

“They’re just blobs of dirty sand sinking back into the sea,” my sailing friend said. “It must be the biggest shipping hazard in the Gulf.”

It could be a metaphor for what has happened to Dubai. Last week the emirate’s carefully crafted image of brash, glitzy modernity dissolved into chaos as Dubai World, the government-owned conglomerate that owns Nakheel, effectively told its bankers and investors that it could not pay its debts.

With some US$60 billion at stake in loans, bonds and outstanding bills, the news sent shock waves around the real world. Investors deserted Dubai in droves. The emirate became as “toxic” as Lehman Brothers and spread its contagion around all the Gulf countries, from Abu Dhabi to Kuwait. Some analysts feared it might be the spark for the feared W-shaped, or double-dip, recession, just as the global economy seemed to be recovering from the credit crisis.

The financial experts will pick over the bones of the “Dubai model” for years to explain what has happened, but the basics are simple: With minimal natural resources in an energy-rich region, Dubai decided to go for broke with an ambitious strategy of economic growth designed to turn the Arab fishing village into a global trading metropolis.

It did it with borrowed money, vast quantities of it. The palm-shaped islands, the glamorous beach resorts, the seven-star hotels, a state-of-the-art metro system — all were built on borrowed money. The last published figure was US$80 billion of debt owed by the government itself and the corporations it owns — like Dubai World. This was around 140 percent of Dubai’s GDP.

Neither I nor any of my friends and colleagues have felt we were living on borrowed time. Life in the emirate is good — great weather most of the year, cheap cars and gasoline and a touch of high life in the swanky hotels. Affordable domestic help is the norm — armies of Filipina and Sri Lankan maids and Indian drivers and gardeners mean that life for expatriates is free from much of the drudgery of Europe or the US.

Property prices were a worry. A three-bedroom villa in a nice part of town — close to the beach and near the arterial highway, Sheikh Zayed Road — would set you back more than £3,000 a month. But salaries were about 50 percent higher than in Europe — and tax free — so it was affordable. The things I liked best about Dubai were summed up in four words: no tax, valet parking.

This was the expat trade-off in the Great Deal done between the al-Maktoum family, rulers of Dubai since 1833, and the expatriate work force that keeps the place going. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, the ruler, guaranteed an environment in which the expats — Europeans, Americans, Asians and Africans — could be well rewarded for hard work and afford to live in the playground of the Gulf; in return we gave him the labor and expertise his own subjects — the privileged Emiratis, who make up fewer than 10 percent of Dubai’s population — were either unwilling or unable to supply. It was a great deal.

The strategy worked until the credit crisis — prompted by a collapse in property prices — threw a wrench in the works of the global financial system. No one wanted to lend any more to Dubai’s property-obsessed economy. No one wanted to buy the “iconic high-rise waterside lifestyle developments” that were planned for the bone-dry desert.

Dubai World’s announcement was confirmation of what many have suspected for some time, but nobody dared admit — especially Dubai’s ruling elite — in denial since the credit crisis began: The emirate is bust, as surely as modern-day Iceland, or Argentina in the 1990s, or Germany in the 1920s. It will not survive in present form without the intervention of outsiders, whether Abu Dhabi, the oil-rich capital of the United Arab Emirates federation Dubai joined in 1972, or the international banks that are already in it for billions, or the global financial authorities.

I have met Mohammed a couple of times, at functions and formal occasions, and heard him speak many times more. As the serving representative of one of the world’s longest surviving hereditary monarchies, he certainly held the attention of his largely Emirati audience. You would expect him, as a hereditary autocrat, to command a certain amount of respect, but there was evidence of his legendary “vision,” too.

A couple of years ago, he said he wanted to make Dubai “an Arab city of global significance, like Cordoba and Baghdad.” He was talking about the two leading urban centrers of the Muslim world at the height of the Islamic empire in the 10th century and that was indeed inspirational, with a grand historical sweep. The Emiratis loved it. I, too, was impressed back then.

A few weeks ago he was speaking in public again, to a group of investors gathered together by a US bank. Unexpectedly, he strayed from his Arabic speech to tell, in English, those who doubted the strength of ties between Abu Dhabi and Dubai to “shut up.”

Many in the audience thought it was demeaning for a man of such international stature and reputation to resort to a near-vulgarity. I thought the strain of Dubai’s financial problems and the effect it was having on Dubai’s reputation abroad was beginning to tell on the 62-year-old monarch.

There is no doubt that Dubai has had a bad year, image-wise. Virtually every couple of weeks some Western correspondent would pop up in the emirate, announce he was “writing a piece on the dark side of Dubai” and leave after a few days in the sun at a five-star beach resort to launch another attack on the emirate and its residents.

There were interviews with exploited Asian workers in filthy labor camps, hilarious encounters with Ukrainian prostitutes in Dubai nightclubs and heart-rending accounts of jailed expats or sacked foreigners having to sleep in their 4x4s. For those of us living and working in the country, it almost seemed like they were writing about somewhere else.

There is a “dark side” to Dubai, like there is to any big city anywhere in the world, in every era of history. Labor exploitation is probably the most obvious scandal. Construction workers from India, Pakistan and China are lured to Dubai with the promise of wages big enough for them to give their families a better life back home, only to have their passports confiscated on arrival as they are hit with huge “fees” for their travel and accommodation. The conditions they live in are primitive compared to the rest of the city and the West (though probably not those of their home countries).

The government blames it on unscrupulous middlemen and promises to take action with each new report. For what it’s worth, it does seem to be getting better. I, like most expats, have largely ignored it, or when I wanted to salve my conscience gave a bigger tip to the Asian waiter or Indian taxi driver and affirmed self-righteously that conditions were surely worse for the Irish navies who built Victorian London or the Chinese coolies who laid the US railroads. It was the price of “diversification away from an oil-dependent economy,” I’d tell myself.

Prostitution is rife, too, mainly women from the former Soviet countries or China, but fairly self-contained in well-known bars and districts. It depends on your attitude to prostitution, I guess. For many visitors it adds a frisson to the city and guarantees that the conference and exhibition trade continues to attract sybaritic high-rolling businessmen from the west. Along with the ready availability of alcohol, it means Dubai will always have a unique marketing advantage compared with Riyadh, or Doha, or even Abu Dhabi. It is maybe a bit worse than the red-light districts of any European or US city. I take the view that if you didn’t want, you wouldn’t go.

If only the Western correspondents who spent so many hours in desert labor camps or Russian cat-houses would take just a couple of hours on a Friday afternoon to visit Safa Park, Dubai’s equivalent of Hyde Park or Hampstead Heath, sprawling between the beach villas of Jumeirah and the slums of Satwa, with the needle spire of Burj Dubai, the world’s tallest building, in the background.

There, Arab families spread their picnic lunches on the lawn, ladies in abaya and men in dishdasha; Indian groups play football and light barbecues; Filipino couples stroll by the fountains, pushing strollers; Westerners lounge in the sun just chilling, maybe taking an occasional swig from a (theoretically) illicit can of beer.

It is a pastoral vision of social, cultural and racial integration that would surely soften the heart of even the most skeptical foreign correspondent. A place like Safa, after lunchtime prayers at the mosque, is what makes Dubai a special place in the Middle East, and which needs to be rescued from the financial wreckage.

Dubai leads the Arabian peninsula in this respect. Christian churches and Hindu temples lie a couple of blocks away from an imposing mosque. There is a synagogue discreetly hidden among the big villas of Jumeirah, built to accommodate a American Jewish banker who would only relocate to Dubai on condition that he could practice his religion. (Mohammed gave his personal assent for construction, apparently.)

Dubai is not just a social and cultural melting pot. It’s also a major commercial hub at the heart of a strategically vital region. The US fleet loads up at Jebel Ali port — owned by Dubai World — before it moves its cargoes on to Iraq and Afghanistan. The Iranians, who have been cross-fertilizing with this part of Arabia for centuries, use Dubai as a social and financial pressure valve. During the recent contested elections in Iran, the biggest demonstrations outside Tehran were in Dubai.

Saudi Arabia, the biggest economic power in the region, uses Dubai as its entrepot to the wider financial world and as an escape from the cloying Islamic orthodoxy of the kingdom. You can see young Saudis in bars and nightclubs most weekends, drinking bottles of Johnny Walker Blue Label (“Saudi Coke”) and trying to chat up Uzbeki ladies in broken English.

Despite all its flaws, Dubai is as close as the Middle East gets to the Islamic concept of “harem” — a place of peace and reconciliation where conflicts and arguments can be forgotten and disputes resolved in a spirit of mutual understanding.

How the emirate resolves the current dispute with its international creditors will determine whether it remains the best hope the Middle East has or reverts to some kind of Islamic isolationism. The fear among expats — and Dubai Emiratis — is that, if Abu Dhabi bails out Dubai, it will exact a high price for its financial lifeblood. It may seek control of crown jewels like the Emirates airline or the DP World ports business, or to take over the Dubai International Financial Center, the region’s closest equivalent to the City of London and Wall Street.

Or it may impose stricter Islamic standards on acceptable public behavior, like forcing women to wear an abaya in public. Despite the occasional furor over a bit of beach bonking, women in Dubai are still the most liberated in the Arab world.

If, on the other hand, Dubai can reach a deal with the banks and bondholders, it may have to sell or cede control of those same assets to Westerners, which would open it up to further accusations of un-Islamic, anti-Arab behavior from its neighbors.

The events of last week — and the repercussions that will roll on for the coming six months as Dubai tries to get its finances back on the straight and narrow — will have a permanent impact on the emirate. It cannot be Bling City any more, and Mohammed’s plans to rival Cordoba and Baghdad will probably have to be shelved for a couple of centuries.

At a posh Thanksgiving dinner party last week, the day after the Dubai World news broke, I counted 10 nationalities among 15 guests.

Americans, Europeans, Arabs and Asians, we were all agreed that things could never be the same again in the emirate and fearful for the future. But equally we were all united in the hope that Dubai’s unique economic, cultural and social experiment should be allowed to continue.

Jack Hughes is the pseudonym for a writer who lives and works in Dubai.

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its