At dusk, Sergeant Levente Saja stands in the open countryside and scans the horizon through binoculars. A dirt road separates a field of maize from a wide expanse of scrub and grass.

“This corn makes our job a lot more difficult,” he said.

The cornfield is in Hungary, a member of the EU and part of the Schengen Zone, which stretches west to Portugal and north to Scandinavia with no internal border checks or further passport scrutiny.

The other field is in war-scarred Serbia, which is not an EU member and where the Balkan ethnic conflicts of the 1990s left the economy and much of its infrastructure in ruins.

Serbia has become one of the main land routes into the EU for those in search of a better life but lacking the documents to enter legally.

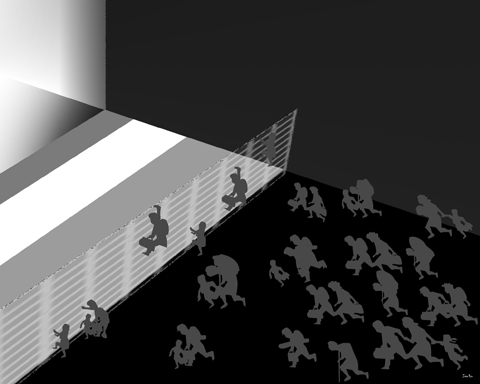

Day and night, men, women and children crawl, run, shuffle and crouch, inching their way across the fields towards Hungary. Saja and his colleagues in the Hungarian border police are tasked with stopping these illegal migrants.

“You never know when they might turn up,” he said.

The Hungary-Serbia border is just one more barrier on a very long journey. Many will have spent months traveling, often on foot, living in unimaginable conditions.

Saja recalls finding an Afghan man just inside the Hungarian border: “He was lying in a field, exhausted, unconscious.”

After receiving medical treatment, the Afghan requested political asylum, making him the responsibility of the Interior Ministry’s Office of Immigration and Nationality.

Most of those apprehended on the “green border,” as it is known, are Roma, or gypsies, from Serbia, and Kosovo Albanians. Africans appear periodically and in recent months the number of Afghan refugees has noticeably increased, said border police officer Major Szabolcs Revesz.

“Hungary is still not a target country for illegal immigrants,” said Lieutenant Colonel Gabor Eberhardt in his office at police headquarters in the university town of Szeged, southern Hungary.

Last week, the EU border control agency Frontex said illegal border crossings into the EU declined by 20 percent in the first half of this year, largely due to stronger border controls and the economic crisis.

However, the agency noted that illegal immigration into Hungary has climbed exponentially.

Eberhardt said: “Most who cross the border illegally are heading for Germany, Switzerland or other wealthier countries.”

His department patrols 62km of Hungary’s border with Serbia and its 68km border with Romania, containing five official border crossings.

Since joining the Schengen Zone in January last year, Hungary has emerged as an attractive destination for migrants keen to get into Western Europe without the proper papers. This rising demand, coupled with the stepped-up security, is reflected in the prices charged by criminal gangs that provide false papers and transport.

“People traffickers in Kosovo used to charge 1,500 euros (US$2,200). Now they are demanding 3,000 euros,” Eberhardt said.

In practice, this fee will often only get the migrant as far as the border: “Clients” are told to split up and make their own way into Hungary before regrouping. This is when they are usually picked up by border police and either sent back to Serbia or into the slow system for processing asylum claims.

Many, who might have already handed over every cent they had for transport to the West, are simply abandoned in Hungary, sometimes even told that they are already in Switzerland or Germany.

Others make their own way on foot, often following railway lines or the few roads that are the only landmarks in the remote, open countryside.

“As some illegal migrants are on the verge of death when we find them, the first thing we have to do is provide them with medical attention,” Eberhardt said.

Border guards insist that it seems impossible to know how many are making it into Hungary illegally, but Eberhardt is confident the number is low.

“I cannot say we are detecting 100 percent of illegal border crossings, but somewhere very close to that,” he said.

The strip of border under Eberhardt’s watch is just one of five stretches of Hungary’s external Schengen borders with neighboring Ukraine, Romania, Serbia and Croatia.

“Although 836 were officially caught in the green border in 2008, the real number of people is probably closer to 2,500,” he said.

The figures only tell part of the story: Children are not included in the official statistics on illegal immigration.

Eberhardt points to a room for mothers and children in the Szeged headquarters, where those apprehended are processed and either returned or sent into the asylum system. The grimness of the barred door and linoleum floor are eased only slightly by a few colorful posters on the wall, rubber play mats and a television.

Officially, more than 900 migrants had been picked up by the end of August, already more than last year’s total. And these were just those caught on Hungary’s part of the Schengen land border, which runs from the tip of Norway inside the Arctic Circle down to Slovenia on the Adriatic.

Saja, the genial sergeant, knows the “green border” like the back of his hand, including which drainage ditches and rows of bushes migrants use for cover.

Despite thermal-imaging cameras and helicopter backup — the EU has poured millions into tightening its expanded eastern border — he and his colleagues more often use simple hunters’ tricks. Inadvertently moving a seemingly innocent branch can betray a migrant’s passage to the guards.

Although they will sometimes try to evade capture by fleeing — into the cornfields, for example — once caught, the illegal migrants are usually passive and put up little resistance.

“They don’t try to fight,” Saja said. “They are usually pretty worn out anyway.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hypersonic missile carried a simple message to the West over Ukraine: Back off, and if you do not, Russia reserves the right to hit US and British military facilities. Russia fired a new intermediate-range hypersonic ballistic missile known as “Oreshnik,” or Hazel Tree, at Ukraine on Thursday in what Putin said was a direct response to strikes on Russia by Ukrainian forces with US and British missiles. In a special statement from the Kremlin just after 8pm in Moscow that day, the Russian president said the war was escalating toward a global conflict, although he avoided any nuclear

Would China attack Taiwan during the American lame duck period? For months, there have been worries that Beijing would seek to take advantage of an American president slowed by age and a potentially chaotic transition to make a move on Taiwan. In the wake of an American election that ended without drama, that far-fetched scenario will likely prove purely hypothetical. But there is a crisis brewing elsewhere in Asia — one with which US president-elect Donald Trump may have to deal during his first days in office. Tensions between the Philippines and China in the South China Sea have been at

US President-elect Donald Trump has been declaring his personnel picks for his incoming Cabinet. Many are staunchly opposed to China. South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, Trump’s nomination to be his next secretary of the US Department of Homeland Security, said that since 2000, China has had a long-term plan to destroy the US. US Representative Mike Waltz, nominated by Trump to be national security adviser, has stated that the US is engaged in a cold war with China, and has criticized Canada as being weak on Beijing. Even more vocal and unequivocal than these two Cabinet picks is Trump’s nomination for

An article written by Uber Eats Taiwan general manager Chai Lee (李佳穎) published in the Liberty Times (sister paper of the Taipei Times) on Tuesday said that Uber Eats promises to engage in negotiations to create a “win-win” situation. The article asserted that Uber Eats’ acquisition of Foodpanda would bring about better results for Taiwan. The National Delivery Industrial Union (NDIU), a trade union for food couriers in Taiwan, would like to express its doubts about and dissatisfaction with Lee’s article — if Uber Eats truly has a clear plan, why has this so-called plan not been presented at relevant