For years, the aim of pretty much every technology company has been to make a product that people can’t give up using, and in case something better comes along from a rival, make sure that they can’t get their stuff — whether it be data, software or hardware — to work easily with the newcomer’s platform. On this rested the success of the compact cassette versus the 8-track, VHS versus Betamax, Iomega’s Zip versus other backup systems and most recently Blu-ray versus HD DVD.

Amid these battles, Brian Fitzpatrick’s role at Google sounds contrary. He runs its self-styled (and half-jokingly named) “Data Liberation Front” in the Chicago offices, and his aim is to make it easier — one button is the ideal — to export your data from Google’s servers onto a storage format of your choice, whether that’s your own Web server, your computer, or the comfort of your backup drive.

The Data Liberation Front (http://bit.ly/googledata) — the name’s a jokey reference to the Judean People’s Front, the would-be terrorist group in Monty Python’s Life of Brian that never quite gets its act together — is actually a good thing for Google’s customers, Fitzpatrick argues, because it means that lock-in element can’t be applied to your data.

“Think of it like you were renting a house,” Fitzpatrick said. “If you decided to move out and the landlord came and told you that you couldn’t take your furniture or your clothes or your family photos, you wouldn’t be pleased, would you?”

His point is that Google wants to give you that comfortable feeling that if you need to export your data then you can.

It’s already been achieved for Blogger, the free blogging platform the company bought. There is a one-click export (to the Atom format) that preserves not only posts but also comments. (An export to RSS, which is also available, only preserves the blog posts.) Google Notebook, which has been “end of lifed” (read: killed off), has had export functionality added to it. Fitzpatrick notes all sorts of Google products that have received export functionality: Google Docs, iGoogle, and various other Google products. (And, inevitably, you can follow it on Twitter at twitter.com/dataliberation.)

And next, he says — though dates aren’t given — there’ll be an “export” button for Google Sites (in HTML), as well as a “mass export” from Google Docs, for those who want to export a lot of data at once.

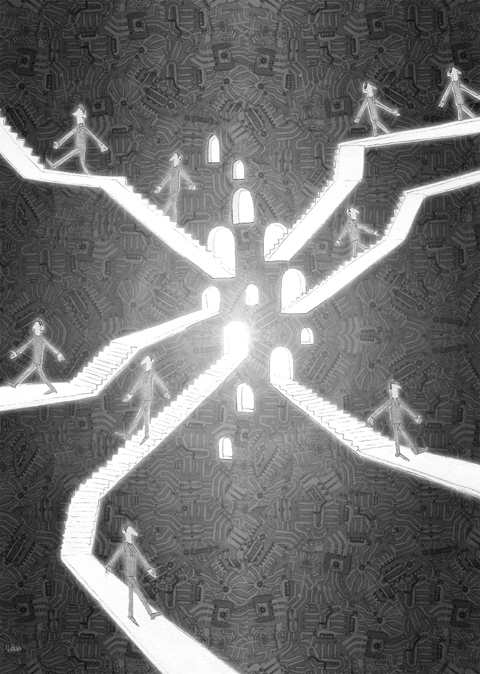

You can see the clever sales logic. Many people fret that with cloud computing you can’t walk up to any location — still less a specific machine — and say: “My data is in here.”

TRUSTING CLOUDS

Such distributed services mean your data might be on five continents at the same time.

Thus people, and companies, get uncomfortable about trusting a cloud service, because they don’t know where it is, and so can’t be sure it’s really safe.

For Google to say “we can easily import your data” isn’t more of a claim than others are already making.

But if it then says “exporting your data is one-button easy,” it actually has a selling point. True, it looks perverse to those accustomed to the lock-in mentality of previous commercial battles. But it may be the right approach for the web. It’s classically, Google-typically, counter-intuitive.

Fitzpatrick studied Latin and Greek at university, then went to work for OnShore, a small networking company based in Chicago. There he got interested in fixing a problem with an open source database driver, and was then encouraged to submit the change to its authors. That led to working on Subversion, a version control system widely used by teams of programmers who need to co-ordinate different versions of programs.

He then went to Apple, where he worked on the consulting team that would go with every sale of its fabulously expensive WebObjects package, and then back to Subversion. (He wrote the book on it, at http://bit.ly/subversionbook.)

When Google bought out the company he was working at, he was reluctant to join: He’d set down roots in Chicago. But the company was happy to let him set up an engineering department in the city. He’s also in charge of Google Affiliate Networks, an acquisition from the takeover of DoubleClick.

“We believe in an open web for everyone ... The Web is fundamentally about openness,” he said.

But there are also two other ways in which it works to Google’s advantage. First, it encourages its developers not to fall behind rivals. If the price of being overtaken is that people will pick up their data and leave your application behind, you’ll have a stronger incentive to keep going.

But equally, for managers who don’t want to have to support a million wilting blooms, being able to export data means that unsuccessful projects can be shut down without regrets that users will curse the company for locking away their data on its servers forever.

Compare that with the outcry that Yahoo faced when it announced it would close Geocities: Efforts to save it sprouted up and Yahoo wasn’t popular. Google isn’t popular for closing services — but at least Google Notebook users can get their data out.

LOOKING FORWARD

So, export for blogs and Google docs is straightforward, as everyone is familiar with their formats. But how will exporting work for a completely novel idea, such as Wave, whose functionality nobody outside Google has yet managed to describe in fewer than a thousand words (it’s something like “e-mail and instant messaging and collaboration but with changes shown over time”)? How do you export something that has a unique format?

For a moment, Fitzpatrick looks faintly alarmed. But that’s not because he hasn’t considered it.

“We have talked about it. It’s not that difficult to represent [its data],” he said. “The question is how to represent time. Wave has the extra dimension of revisions. There are ways to represent that but nothing else really has anything that it’s like. It’s unique.”

What about Wikipedia’s “diff,” which shows the differences between revised versions of the same page?

“That’s perhaps the closest,” Fitzpatrick said.

The problem then is that a diff is a database representation and there isn’t an agreed way to export a database.

The irony is that if Fitzpatrick succeeds, then Eric Schmidt, Google’s chief executive, will probably be happy.

“He keeps telling us, the way to not be evil is to not lock users in,” Fitzpatrick said. “He tells us, just get the users and we’ll figure out how to make money.”

The image was oddly quiet. No speeches, no flags, no dramatic announcements — just a Chinese cargo ship cutting through arctic ice and arriving in Britain in October. The Istanbul Bridge completed a journey that once existed only in theory, shaving weeks off traditional shipping routes. On paper, it was a story about efficiency. In strategic terms, it was about timing. Much like politics, arriving early matters. Especially when the route, the rules and the traffic are still undefined. For years, global politics has trained us to watch the loud moments: warships in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions announced at news conferences, leaders trading

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.