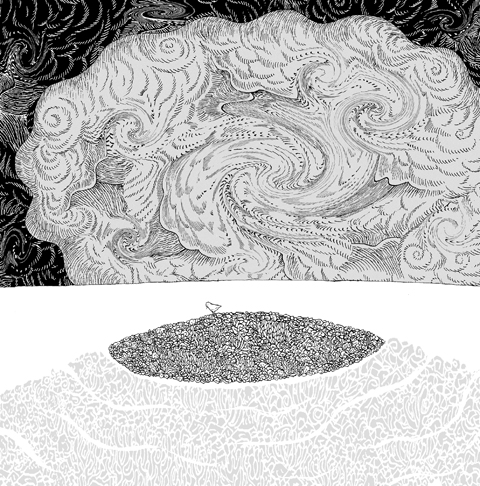

Animal, vegetable and mineral, a pristine tropical coral reef is one of the natural wonders of the world. Bathed in clear, warm, water and thick with a psychedelic display of fish, sharks, crustaceans and other sea life, the colorful coral ramparts that rise from the sand are known as the rainforests of the oceans.

And with good reason. Reefs and rainforests have more in common than their beauty and bewildering biodiversity. Both have existed for millions of years, and yet, now, both are poised to disappear. If you thought you had heard enough bad news concerning the environment and considered that the situation could not get any worse, then steel yourself.

Coral reefs are doomed. The situation is virtually hopeless. Forget ice caps and rising sea levels: the tropical coral reef looks as if it will enter the history books as the first large-scale ecosystem wiped out by our love of cheap energy.

A report from the Australian government agency that looks after the nation’s emblematic Great Barrier Reef reported on Sept. 2 that “the overall outlook for the reef is poor, and catastrophic damage to the ecosystem may not be averted.”

The Great Barrier Reef is in trouble, and it is not the only one.

Within just a few decades, experts are warning, the tropical reefs strung around the middle of our planet like a jeweled corset will reduce to rubble.

“The future is horrific,” said Charlie Veron, an Australian marine biologist who is widely regarded as the world’s foremost expert on coral reefs. “There is no hope of reefs surviving to even mid-century in any form that we now recognize. If, and when, they go, they will take with them about one-third of the world’s marine biodiversity.”

DOMINO EFFECT

“Then there is a domino effect, as reefs fail so will other ecosystems. This is the path of a mass extinction event, when most life, especially tropical marine life, goes extinct,” Veron said.

Alex Rogers, a coral expert with the Zoological Society of London, talks of an “absolute guarantee of their annihilation.”

And David Obura, another coral heavyweight and head of CORDIO East Africa, a research group in Kenya, is equally pessimistic.

“I don’t think reefs have much of a chance. And what’s happening to reefs is a parable of what is going to happen to everything else,” he said.

These are desperate words, stripped of the usual scientific caveats and expressions of uncertainty, and they are a measure of the enormity of what’s happening to our reefs.

The problem is a new take on a familiar evil. Of the billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide spewed from cars, power stations, aircraft and factories each year, about half hangs in the thin layer of atmosphere where it traps heat at the Earth’s surface and so drives global warming.

What happens to the rest of this steady flood of carbon pollution? Some is absorbed by the world’s soils and forests, offering vital respite to our overcooked climate. The remainder dissolves into the world’s oceans. And there, it stores up a whole heap of trouble for coral reefs.

Often mistaken for plants, individual corals are animals closely related to sea anemones and jellyfish. They have tiny tentacles and can sting and eat fish and other small animals. Corals are found throughout the world’s oceans, and holidaymakers taking a swim off the Cornish coast may brush their hands through clouds of the tiny creatures without ever realizing they have encountered coral.

It is when corals form communities on the seabed that things get interesting. Especially in the tropics. Britain has its own coral reefs, but these deep-water natural constructions are remote, cold and dark, and frequently fail to fire the imagination. It is in shallow, brightly light waters, that coral reefs really come to life. In the turquoise waters of the Caribbean, Indian Ocean and Pacific, the coral come together with tiny algae to make magic.

The algae do something that the coral cannot. They photosynthesise, and so use the sun’s energy to churn out food for the coral. In return, the coral provide the algae with the carbon dioxide they need for photosynthesis, and so complete the circle of symbiotic life.

Freed of the need to wave their tentacles around to hunt for food, the coral can devote more energy to secreting the mineral calcium carbonate, from which they form a stony exoskeleton.

A second type of algae, which also produces calcium carbonate, provides the cement. Together, the marine menage-a-trois make a very effective building site, with dead corals leaving their calcium skeletons behind as limestone.

FRAGILITY

For all their apparent beauty and fragility, just think of coral reefs as big lumps of rock with a living crust.

But it is fragile crust. And the natural world is a harsh environment for coral reefs. They are under perpetual attack by legions of fish that graze their fields of algae. Animals bore into their shells to make homes, and storms and crashing waves break them apart. They may appear peaceful paradises, but most coral reefs are manic sites of constant destruction and frantic rebuilding.

Crucially though, for many millions of years, these processes have been in balance.

Human impact has tipped that balance. Loaded with agricultural nutrients — nitrates and phosphates — rivers spill polluted water into the sea. Sediment and sewage cloud the clear waters, while overfishing plays havoc with the finely tuned community of fish, including sharks, that otherwise keep the reef nibbled down to sustainable levels.

All of this might have been enough to kill off coral without any help from the impact of climate change. But global warming has delivered the coup de grace. Secure in their tropical currents, coral reefs have evolved to operate within a fairly narrow temperature range, and, in the late 1970s and 1980s, scientists got an unpleasant demonstration of what happens when the hot tap is left on too long.

“The algae go berserk,” Rogers said.

Scientists suspect the algae react to the warmer water and increased sunlight by producing toxic oxygen compounds called superoxides, which can damage the coral. The coral respond by ejecting their algal lodgers, leaving the reefs starved of nutrients and deathly white.

BLEACHING

Such bleaching was first observed on a large scale in the 1980s, and reached massive levels worldwide during the 1997-1998 El Nino weather event. On top of the human-warmed climate, that El Nino, as always caused by pulses of warming and cooling in the Pacific, drove water temperatures across the world beyond the comfort zone of the coral

The mass bleaching event that followed killed a fifth of coral communities worldwide, and though many have recovered slightly since, the global death toll attributed to the 1997-1998 mass bleaching stands at 16 percent.

“At the moment the reefs seem to be recovering well but it’s only a matter of time before we have another [mass bleaching event],” Obura said.

With its striking images of skeletal reefs stripped of color and life, coral bleaching offers photogenic evidence of our crumbling biodiversity, and has placed the plight of reefs higher on the world’s consciousness.

Katy Bloor, a teacher at Sub-Mission Dive School, in Stoke-on-Trent, said many divers are not aware of the problems corals face, particularly as holiday operators tend to visit reefs that are in better condition.

“Most have probably dived on a coral reef that they thought was a bit rubbish, but they haven’t considered why,” she said.

The plight of the reefs has received less attention than have terrestrial ecosystems, such as forests, said Veron, because coral experts have failed to raise the alarm.

“Coral reef scientists are a closely networked group, coral reefs being quite unlike anything else. Individual scientists rarely communicate with their colleagues. This has to change,” Veron said.

Can the coral be helped? If planting more trees can regrow a forest, can coral be introduced to bolster failing reefs? There are a handful of groups working on the problem, many of which have reported encouraging results.

But the problem with all these efforts, Rogers said, is that they cannot address the looming holocaust that reefs face. A new, terrible, curse that comes on top of the bleaching — the battering, the poisoning and the pollution.

ACIDIC SEAS

Remember the carbon dioxide that we left dissolving in the oceans? Billions and billions of tonnes of it over the last 150 years or so since the industrial revolution? While mankind has squabbled, delayed, distracted and dithered over the impact that carbon emissions have on the atmosphere, that dissolved pollution has been steadily turning the oceans more acidic.

There is no dispute, no denial, about this one. Chemistry is chemistry, and carbon dioxide plus water has made carbonic acid since the dawn of time.

As a consequence, the surface waters of the world’s oceans have dropped by about 0.1 pH unit — a sentence that proves the hopeless inadequacy of scientific terminology to express certain concepts. It sounds small, but is a truly jaw-dropping change for coral reefs. For reefs to rebuild their stony skeletons, they rely on the seawater washing over them to be rich in the calcium mineral aragonite.

Put simply, the more acid the seawater, the less aragonite it can hold, and the less likely corals can rebuild their structure.

This year, a paper in the journal Science reported that calcification rates across the Great Barrier Reefs have dropped 14 percent since 1990. The researchers said more acidic seas were the most likely culprit, and ended their sober write-up of the study with the extraordinary warning that it showed “precipitous changes in the biodiversity and productivity of the world’s oceans may be imminent.”

Rogers said carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere are already over the safe limit for coral reefs. And even the most ambitious political targets for carbon cuts, based on limiting temperature rise to 2°C, are insufficient.

Their only hope, he said, is a long-term carbon concentration much lower than today’s. The clock must somehow be wound back and carbon sucked out of the air. If not, then so much more carbon will dissolve in the seas that the reefs will surely crumble to dust. Given the reluctance to reduce emissions so far, the coral community is not holding its breath.

“I just don’t see the world having the commitment to sort this one out,” Obura said. “We need to use the coral reef lesson to wake us up and not let this happen to a hundred other ecosystems.”

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals