Former US vice president Al Gore made a surprise appearance on the sketch comedy program Saturday Night Live in May 2006 to offer an alternative-universe United States, one in which he’d become president after the 2000 election fiasco. Global warming was so soundly defeated that glaciers stood poised to attack Michigan and Maine. All Americans enjoyed free health care. The rest of the world held the US in such high esteem that Americans were afraid to travel to Europe for fear of being hugged too much.

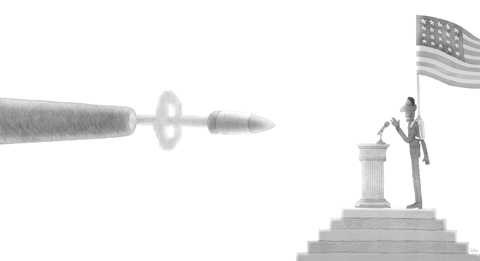

By January of this year, many believed that this liberal fantasy had become liberal promise. A slight and handsome man, with ears sensitive to 300 million disparate voices, had appeared. President-elect Barack Obama reminded Americans in his weekly address of the impossible hand history had dealt him, the two wars, the economic crisis, the health care crisis, the climate crisis.

Remarkably, things that Obama said in those pre-inaugural weekly addresses would have been — no, were! — sketch comedy just two years before. An alternative universe had set upon us, vividly evidenced by the 200,000 Germans prepared to embrace a US presidential candidate in Berlin last summer. Climate change and health care might not have been licked just yet, but they’d better watch out.

Eight months into Obama’s presidency, foreign observers might be forgiven for asking why haven’t all those winged words lifted US climate policy from its rut? The man who admonished Americans: “We can’t fall into the old Washington habit of throwing money at the problem” has run into old Washington habits.

Here’s the story to date. Obama and his team built a compelling narrative in the campaign. There was so much bad news last year and so many intractable problems that everything was beginning to dovetail. A big story was coming together: All of our crises — Wall Street, “Main Street,” climate, health care — were entwined. The solutions must be, too. Climate change requires a new kind of economy, powered by the sun, wind and emissions-free coal-burning. A new economy requires a rationalized healthcare system, free of waste and poor judgment.

A campaign is monologic. The problem, once you live in the White House, is the other people who were elected to Washington and enjoy the standing they’ve earned. They would like to keep their jobs but might not be able to if they rubber-stamped all a president’s solutions.

The Democrats have already achieved an impressive and perhaps unlikely victory. It’s easy to forget in the noise. Climate change emerged as a national story this spring, when a powerful House of Representatives committee produced a “cap and trade” bill. The White House played a quieter role than many supporters envisioned, given the hoopla surrounding Obama’s advisory “dream team,” which includes former Environmental Protection Agency chief Carol Browner as climate tsar, Nobel laureate Steven Chu at the Department of Energy and Harvard global change expert John Holdren as chief science adviser.

One school argued that the White House so thoroughly trusted veteran Democrat Henry Waxman to lead the charge that they outsourced all the work to him. Another school sensed equivocation in a White House that didn’t want to waste precious political capital on a doomed climate bill. After all, climate change is easy to construe as a lose-lose proposition.

As retired General Anthony C. Zinni recently told the New York Times: “We will pay for this one way or another ... we will pay to reduce greenhouse gas emissions today and we’ll have to take an economic hit of some kind. Or we will pay the price later in military terms and that will involve human lives.”

It’s difficult to say at this moment which climate negotiation faces greater obstacles — that in the US Senate or the multilateral talks in Copenhagen in December.

The easiest move for the new administration was to show the world a new face. The pace of meetings has been accelerating for months. A recent feelgood US-China summit in Washington brought out Obama’s climate-hawk rhetoric. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and other senior officials have logged many air miles but little substantive progress.

The structure of the US Senate makes the passage of complex legislation difficult. We live in the age of the sanitized filibuster. One hundred senators have the power to halt legislation. Climate change is more than a partisan issue; it’s a regional issue.

Democratic senators from Midwestern states whose utilities burn coal for electricity fear their constituents will see higher energy bills if carbon dioxide emissions have a price. Manufacturing states fear that their jobs will depart for nations who have no climate policy.

Earlier this month, 10 Democrats sent Obama a letter saying that they would not vote for a bill that failed to adequately protect their states. Without their votes, the bill is unlikely to succeed.

The complexity of the healthcare debate is dampening appetites for the potentially more complex climate bill. International climate experts in Washington have been wondering for months how US healthcare woes, as they affect the Senate climate debate, may affect the UN-sponsored climate talks in Copenhagen.

Part of the problem lies in the White House’s poor shepherding of the issue.

Another part clearly lies in the impoverished US civic discourse. Lately it feels like all you have to do to get on national television or, more important, on everyone’s Facebook feeds, is compare Obama to Hitler or call him the Great Socialist.

Last week in Houston, 3,500 people, many of them energy industry workers, attended an anti-climate bill program. More are expected in 19 states in coming weeks.

This atmosphere does not tolerate complexity. Yet everything about climate change, from science to policy, resists simplification.

The real paradox comes when you step back from Washington and see that vast swaths of the economy are ready and, in key cases, advocating a US climate policy. Microsoft and General Motors are in the UK’s Confederation of British Industry and party to its climate change positions. So, even if this should turn out not to be the year, sooner or later the feeling of inevitability in the economy that the US will have a price on carbon will intersect with the US actually having a price on carbon.

The US president is the most powerful person in the world. But when it comes to moving transformative legislation through a divided Congress, that is not always true. Both politics and the structure of the US government itself conspire to make this so.

Great presidential achievements require more than a vision of a better, alternative universe, more than hard work and more than the US Treasury’s checkbook — they require most everybody else in town.

Eric Roston is author of The Carbon Age: How Life’s Core Element Has Become Civilization’s Greatest Threat. He writes ClimatePost.net for the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University in Washington.

US political scientist Francis Fukuyama, during an interview with the UK’s Times Radio, reacted to US President Donald Trump’s overturning of decades of US foreign policy by saying that “the chance for serious instability is very great.” That is something of an understatement. Fukuyama said that Trump’s apparent moves to expand US territory and that he “seems to be actively siding with” authoritarian states is concerning, not just for Europe, but also for Taiwan. He said that “if I were China I would see this as a golden opportunity” to annex Taiwan, and that every European country needs to think

For years, the use of insecure smart home appliances and other Internet-connected devices has resulted in personal data leaks. Many smart devices require users’ location, contact details or access to cameras and microphones to set up, which expose people’s personal information, but are unnecessary to use the product. As a result, data breaches and security incidents continue to emerge worldwide through smartphone apps, smart speakers, TVs, air fryers and robot vacuums. Last week, another major data breach was added to the list: Mars Hydro, a Chinese company that makes Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as LED grow lights and the

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals

US President Donald Trump is an extremely stable genius. Within his first month of presidency, he proposed to annex Canada and take military action to control the Panama Canal, renamed the Gulf of Mexico, called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy a dictator and blamed him for the Russian invasion. He has managed to offend many leaders on the planet Earth at warp speed. Demanding that Europe step up its own defense, the Trump administration has threatened to pull US troops from the continent. Accusing Taiwan of stealing the US’ semiconductor business, it intends to impose heavy tariffs on integrated circuit chips