In recent months, two big computer chipmakers slipped through Dresden’s fingers, challenging the notion that an area that likes to think of itself as “Silicon Saxony” can continue to churn out high-technology devices by the millions. But not every inhabitant of this picturesque city considers that a bad thing.

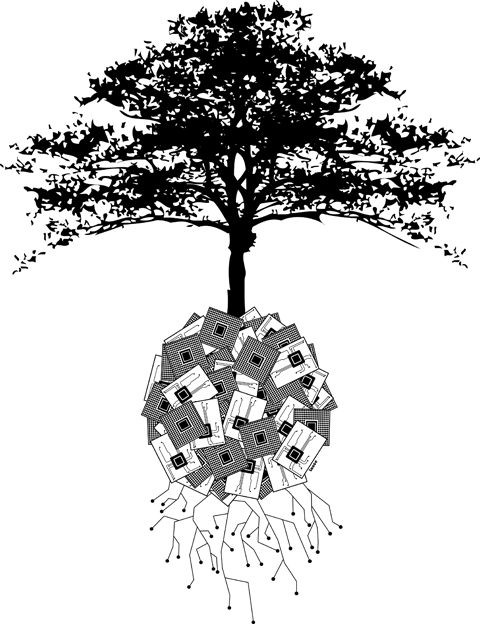

The loss has fired a debate over whether the future of Dresden, in what was once East Germany, should lie more in research and design rather than manufacturing, and few are more passionate about the intellectual side of the chipmaking business than the young entrepreneurs at Blue Wonder Communications. Barely four months old, the company is angling for a piece of the lucrative business in designing chips for the next generation of wireless technology.

Not one of its employees, almost all of them engineers, will actually manufacture anything.

“We need to put money in places that create knowledge, not things,” said Wolfram Drescher, one of two co-chief executives at the company. “If all we had were production and not knowledge, I’d be standing on the street, unemployed.”

The thought that traditional manufacturing should not necessarily be the indispensable foundation of the economy is heresy in Germany. But as China moves to supplant Germany as the world’s largest exporter of goods, the questions here over where to invest for the future go to the heart of an issue that Americans have faced for decades but that Germans are just beginning to confront.

The best examples of this tension come from Dresden. This year, the region’s largest private-sector employer — the chipmaker Qimonda — went bankrupt, while another, Global Foundries, broke ground in upstate New York on a new plant that Dresden had sought for itself.

DRESDEN LOSES OUT

Qimonda, a venture part-owned by memory chipmaker Infineon, turned to Thomas Jurk, Saxony’s economy minister, for help earlier this year. But when he traveled to Berlin to discuss the company’s situation with political leaders, he found that the chipmaker’s troubles were not their top priority. At the time, the government was focused on rescuing Opel, the main European subsidiary of the bankrupt General Motors.

“I heard first that they cared about Opel,” Jurk said, “and second that they cared about — Opel.”

Qimonda’s request for help ultimately proved too large for the state to save the company, and its insolvency cost, directly or indirectly, up to 6,000 jobs in the Dresden region.

Dresden started to become a center for high technology in 1999, when Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) built a chip fabrication plant to make microprocessors for personal computers. Suppliers of things like clean-room technology and masks sprang up around the region, and from 2002 to 2007, the number of people employed in the semiconductor industry more than doubled to 43,000.

This year, AMD split off its manufacturing business into Global Foundries, a joint venture with an investor from Abu Dhabi, and it is still a huge piece of the area’s economy. But Global Foundries, rather than expanding here, was drawn by a subsidy package of roughly US$1.2 billion to build its newest fabrication plant in Saratoga County, in upstate New York. It broke ground late last month.

Drescher says that Saxony needs to focus on what it can deliver — smart people — rather than play the subsidy game in a bid to sway decisions about where chipmakers will build plants.

Blue Wonder will design chips for the next generation of mobile phones, based on the emerging technical standard known as Long Term Evolution, or LTE. The company is in its infancy but the staff is not; most of them already know one another from working on another start-up together, a company that eventually became part of NXP, a spinoff of the Dutch electronics giant Philips, which closed its Dresden research center last year.

In truth, many were happy to go. Drescher recalls a smile creeping across a colleague’s face when the decision was announced.

“The fun factor is gone when your company is suddenly large,” Drescher said.

Barely six months later they were ensconced in a new office, on the third floor of a small office building that looks down on the Elbe River.

On a recent morning, Drescher, 43, clicked through a series of PowerPoint slides for Jurk.

“Knowledge beats production,” screamed one slide, while another drove the point home to the man who sometimes steers tax money toward local companies: “Saxony has to invest in development, less in production.”

Later, behind closed doors, Drescher delivered a pitch to Jurk, one his ministry is still mulling over. Blue Wonder needs test chips — products that incorporate its designs as prototypes — and is asking the state of Saxony to help finance them.

Blue Wonder, aware of the advantage of working with a German producer, wants to rely on the Global Foundries plant in Dresden, which is eager to diversify its roster of clients.

POLITICAL REALITIES

The idea reflects the political realities in Saxony, and indeed, Germany.

“I would say that the preference for manufacturing is at least as strong here as it is anywhere in Germany,” said Heinz Martin Esser, a managing director of Silicon Saxony, the industry’s local trade association.

It is, he added, “in the blood of the Saxons.”

The state worked hard early this decade to attract Porsche and BMW factories to Leipzig, its other major city after Dresden. And Chemnitz, once known as Karl-Marx-Stadt, has become a center for machine-tool makers.

Jurk, a 20-year veteran of Saxon politics, responded earlier this year to Qimonda’s request for help because he was sensitive to the fact that production facilities tended to employ more people than research labs.

Moreover, Qimonda supported a range of capital-intensive research efforts around Dresden.

No one knew that better than Juergen Ruestig, the scientific director of Namlab, a research center that was a partnership between Qimonda and a local university, which took over the insolvent company’s share of the venture.

Namlab’s research into nanotechnology will eventually help create more compact chip designs, and Ruestig had planned on sounding out what might interest the market through its partnership with Qimonda.

“Producers are your connection to the customer,” Ruestig said.

That’s a powerful argument, but Drescher counters that making things yourself is not as critical as it once was.

Qualcomm, one of the world’s largest makers of communications chips, owns nary a factory. And the place where the industry all began just lost its last semiconductor plant, without losing its dynamism, Drescher said.

“Silicon Valley isn’t a factory anymore,” he said. “It’s a think tank.”

US President Donald Trump is systematically dismantling the network of multilateral institutions, organizations and agreements that have helped prevent a third world war for more than 70 years. Yet many governments are twisting themselves into knots trying to downplay his actions, insisting that things are not as they seem and that even if they are, confronting the menace in the White House simply is not an option. Disagreement must be carefully disguised to avoid provoking his wrath. For the British political establishment, the convenient excuse is the need to preserve the UK’s “special relationship” with the US. Following their White House

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

After the confrontation between US President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy on Friday last week, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, discussed this shocking event in an interview. Describing it as a disaster “not only for Ukraine, but also for the US,” Bolton added: “If I were in Taiwan, I would be very worried right now.” Indeed, Taiwanese have been observing — and discussing — this jarring clash as a foreboding signal. Pro-China commentators largely view it as further evidence that the US is an unreliable ally and that Taiwan would be better off integrating more deeply into