“Scientists discover Easter Island ‘fountain of youth’ drug that can extend life by 10 years,” a recent newspaper headline read.

“Coffee may ‘reverse’ Alzheimer’s,” another said.

Amazing and shocking stuff, but there’s a caveat — the research that fueled the stories was done on mice.

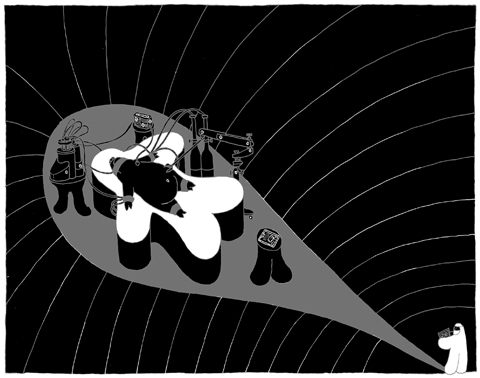

Mus musculus is the creature most experimented on in the history of humanity and you can bet that any modern pharmaceutical medical treatment or basic understanding of genetics has involved working on a mouse at some point. Approximately 85 percent of all animals used in experiments are rodents and the vast majority of those are mice.

And for good reason.

“Mice are used because they’re the smallest and one of the easiest mammals to study in a laboratory setting — they breed quickly and are good enough for many types of study,” says Simon Festing, chief executive of the UK pro-research charity Understanding Animal Research.

“While there are differences, we know that the main biological body systems work in the same way in all mammals. The reproductive, endocrine and cardiovascular and the central nervous systems all have a very similar structure and function,” he says. “Mice share over 90 percent of their genes with humans.”

However, using a mouse can never tell scientists everything they need to know. A result on a mouse is an interesting lead but only replication in a higher animal, such as a dog or a monkey, pushes it closer to becoming a reality for people. In the case of the Easter Island elixir (a drug called rapamycin), reports suggested that the anti-aging pill made from chemicals found on the islands had extended the life of mice by up to 38 percent — but the researchers warned that humans should not think about using the drug to extend life because it suppresses immunity.

And the Alzheimer’s study, published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, showed that caffeine could slow down the build-up of protein plaques, which are the signature of the disease and cause the damage to the brain. The mice were given the equivalent of five cups of coffee per day, containing around 500mg of caffeine, and showed almost a 50 percent reduction in the levels of the protein plaques in their brains after two months. But the scientists cautioned that, though caffeine was a relatively safe drug, there was no indication yet about the amounts of the chemical that would act successfully against Alzheimer’s in humans. And pregnant women and people with high blood pressure should certainly avoid upping their caffeine intake.

There are several reasons why results on mice have problems translating directly to humans. When researching whether a drug works, doses on mice are sometimes much higher than anything that a doctor could safely use on a patient, even allowing for adjustments of metabolic rate and size. “Because your primary concern in the animal experiments is to demonstrate an effective treatment, you will dose higher than you would in a human,” says Dominic Wells, head of the department of cellular and molecular neuroscience at Imperial College London.

“So if you hear a story that a mouse has been cured of this or that, you need to take that with a big pinch of salt because we would almost certainly not be allowed to take the same sort of dose rate straight into a human. We’d need to make a significant reduction to test for safety before we could consider upping the dose,” he says.

Trials using animals tend to focus on a single question — efficacy or toxicity, for example. But to make something suitable for humans requires the management of side-effects, and this might take years to tackle.

In 2006, Daniel Hackam of the University of Toronto looked at how many animal-based experiments had been later verified by successful human trials. Out of 76 studies published between 1980 and 2000, 28 were successfully replicated in human randomized trials, 14 were contradicted in trials and 34 remained untested.

In a letter published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Hackam wrote: “Patients and physicians should remain cautious about extrapolating the findings of prominent animal research to the care of human disease ... poor replication of even high-quality animal studies should be expected by those who conduct clinical research.”

There are also physiological limitations.

“We can genetically modify, by a single intramuscular injection, a whole muscle in a mouse,” Wells says. “If we try to do that in a person it just doesn’t work because the spread of the agent we inject is maybe 4 to 5 millimeters — the size of a mouse muscle.”

And in other areas, mice are not sophisticated enough to model humans.

Neurologically, “mice are wired in a different way,” Wells says. “If I showed you a blind mouse and a mouse with perfect eyesight in a cage, you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference because mice rely a lot on smell and touch.”

None of this should put a negative spin, however, on the importance of mice in research. So far, 26 Nobel prizes have gone to discoveries where research on mice has been key, including work on vitamins, the discovery of penicillin, the development of numerous vaccines and understanding the role of viruses.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a