What international association brings together 18 countries straddling three continents thousands of kilometers apart, united solely by their sharing of a common body of water?

That is a quiz question likely to stump the most devoted aficionado of global politics. It’s the Indian Ocean Rim Countries’ Association for Regional Cooperation, blessed with the unwieldy acronym IOR-ARC, perhaps the most extraordinary international grouping you have ever heard of.

The association manages to unite Australia and Iran, Singapore and India, Madagascar and the United Arab Emirates, and a dozen other states large and small — unlikely partners brought together by the fact that the Indian Ocean washes their shores. I have just come back from attending the association’s ministerial meeting in Sanaa, Yemen. Despite being accustomed to my eyes glazing over at the alphabet soup of international organizations I have encountered during a three-decade-long UN career, I find myself excited by the potential of IOR-ARC.

Regional associations have been created on a variety of premises: geographical, as with the African Union; geopolitical, as with the Organization of American States; economic and commercial, as with ASEAN or Mercosur; and security-driven, as with NATO. There are multi-continental ones, too, like IBSA, which brings together India, Brazil and South Africa, or the better-known G8.

Even Goldman Sachs can claim to have invented an intergovernmental body, since the “BRIC” concept coined by that Wall Street firm was recently institutionalized by a meeting of the heads of government of Brazil, Russia, India and China in Yekaterinburg, Russia, last month. But it is fair to say there is nothing quite like IOR-ARC in the annals of global diplomacy.

For one thing, there is not another ocean on the planet that takes in Asia, Africa and Oceania — and could embrace Europe, too, since the French department of Reunion, in the Indian Ocean, gives France observer status in IOR-ARC, and the French foreign ministry is considering seeking full membership.

For another, every one of Samuel Huntington’s famously clashing civilizations finds a representative among its members, giving a common roof to the widest possible array of world views in their smallest imaginable combination (just 18 countries). When IOR-ARC meets, new windows are opened between countries separated by distance as well as politics.

Malaysians talk with Mauritians, Arabs with Australians, South Africans with Sri Lankans, and Iranians with Indonesians. The Indian Ocean serves as both a sea separating them and a bridge linking them together.

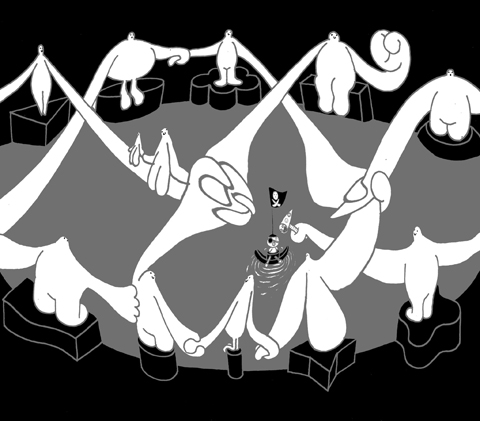

The potential of the organization is huge. There are opportunities to learn from one another, to share experiences and to pool resources on such issues as blue-water fishing, maritime transport and piracy in the Gulf of Aden and the waters off Somalia, as well as in the Strait of Malacca.

But IOR-ARC does not have to confine itself to the water: It’s the countries that are members, not just their coastlines. So everything from the development of tourism in the 18 countries to the transfer of science and technology is on the table. The poorer developing countries have new partners from which to receive educational scholarships for their young and training courses for their government officers. There is already talk of new projects in capacity building, agriculture and the promotion of cultural cooperation.

This is not to imply that IOR-ARC has yet fulfilled its potential in the decade that it has existed. As often happens with brilliant ideas, the creative spark consumes itself in the act of creation, and IOR-ARC has been treading water, not having done enough to get beyond the declaratory phase that marks most new initiatives. The organization itself is lean to the point of emaciation, with just a half-dozen staff — including the gardener — in its Mauritius secretariat. The formula of pursuing work in an Academic Group, a Business Forum and a Working Group on Trade and Investment has not yet brought either focus or drive to the parent body.

But such teething pains are inevitable in any new group, and the seeds of future cooperation have already been sown. Making a success of an association that unites large countries and small ones, island states and continental ones, Islamic republics, monarchies and liberal democracies, and every race known to mankind, represents both a challenge and an opportunity.

This diversity of interests and capabilities can easily impede substantive cooperation, but it can also make such cooperation far more rewarding. In this diversity, we in India see immense possibilities, and in Sanaa we pledged ourselves to energizing and reviving this semi-dormant organization. The brotherhood of man is a tired cliche, but the neighborhood of an ocean is a refreshing new idea. The world as a whole stands to benefit if 18 littoral states can find common ground in the churning waters of a mighty ocean.

Shashi Tharoor, minister of state for external affairs for India, is a former UN undersecretary-general and an award-winning novelist and commentator.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

Why is Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) not a “happy camper” these days regarding Taiwan? Taiwanese have not become more “CCP friendly” in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) use of spies and graft by the United Front Work Department, intimidation conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Armed Police/Coast Guard, and endless subversive political warfare measures, including cyber-attacks, economic coercion, and diplomatic isolation. The percentage of Taiwanese that prefer the status quo or prefer moving towards independence continues to rise — 76 percent as of December last year. According to National Chengchi University (NCCU) polling, the Taiwanese

It would be absurd to claim to see a silver lining behind every US President Donald Trump cloud. Those clouds are too many, too dark and too dangerous. All the same, viewed from a domestic political perspective, there is a clear emerging UK upside to Trump’s efforts at crashing the post-Cold War order. It might even get a boost from Thursday’s Washington visit by British Prime Minister Keir Starmer. In July last year, when Starmer became prime minister, the Labour Party was rigidly on the defensive about Europe. Brexit was seen as an electorally unstable issue for a party whose priority

US President Donald Trump’s return to the White House has brought renewed scrutiny to the Taiwan-US semiconductor relationship with his claim that Taiwan “stole” the US chip business and threats of 100 percent tariffs on foreign-made processors. For Taiwanese and industry leaders, understanding those developments in their full context is crucial while maintaining a clear vision of Taiwan’s role in the global technology ecosystem. The assertion that Taiwan “stole” the US’ semiconductor industry fundamentally misunderstands the evolution of global technology manufacturing. Over the past four decades, Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, led by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), has grown through legitimate means

Today is Feb. 28, a day that Taiwan associates with two tragic historical memories. The 228 Incident, which started on Feb. 28, 1947, began from protests sparked by a cigarette seizure that took place the day before in front of the Tianma Tea House in Taipei’s Datong District (大同). It turned into a mass movement that spread across Taiwan. Local gentry asked then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) to intervene, but he received contradictory orders. In early March, after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) dispatched troops to Keelung, a nationwide massacre took place and lasted until May 16, during which many important intellectuals