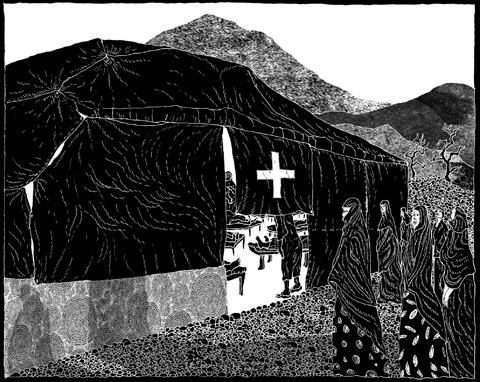

The lone hospital in this tatty Kashmiri mountain town was on the eve of hosting one of the year’s biggest social gatherings, a health fair for several hundred villagers, and Todd Shea was not happy.

The hospital’s founder, Shea, an American who resembles a football coach more than a health worker, was outraged because one of the employees had failed to purchase enough hygiene kits — freebies the villagers had come to expect at the fair.

“This is a problem, and there is a solution,” Shea, strident but good-natured, yelled to a staffer on the phone from the field. “Let’s see how good you are. I know there are kits lurking in the walls. I guarantee you that if I come there, I will find them. You know me!”

Seven hours later, at midnight, the employee returned from a nearby city with a sheepish smile and 100 kits he had managed to round up.

Shea offered him a hug.

“I believe in you,” he said.

If Shea, 42, had a resume, it would by his own admission reveal far more experience as a cocaine addict than as a medical professional. But with his take-charge demeanor, he has transformed primary health care here in this mountain town in Kashmir, where government services are mostly invisible.

“Others are more qualified, but I’m the one who’s here,” he said.

Most recently, he has focused on the millions of people who have been uprooted by the army’s campaign against the Taliban, in the northwest.

But it is here that Shea spends his time and where he learned years ago that, as far as health care is concerned, every day is a crisis for Pakistanis.

He arrived as a volunteer rescue worker immediately after the 2005 earthquake that killed 80,000 Pakistanis. Overwhelmed by the community’s long-term needs, Shea never left, and in 2006 he set up a nonprofit charity hospital called Comprehensive Disaster Relief Services (CDRS).

Humanitarian aid flooded the region in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, but the tide of aid and government support ebbed within months, leaving 25,000 wounded residents without doctors, medical supplies and an actual health outpost. That is, life returned to normal.

In Pakistan, less than 1 percent of the national budget is devoted to the health of its citizens, and the nation’s health care crisis is especially acute in remote communities.

“It’s frustrating and sad that’s the way it is,” Shea said. “But if I screamed from the mountaintop, it wouldn’t change a thing.”

So he does what he can. His hospital, with 38 employees and nearly US$200,000 in financing from Americans and UNICEF, highlights not only the desperate needs of Pakistan’s rural health system, but a glaring vulnerability for a government trying to brand itself an alternative to the Taliban.

“The Taliban terrorize people, but they put forth logical arguments about the state’s failures,” said Shandana Khan, the chief operating officer of the Rural Support Program Network.

“It’s very common to see primary health care facilities without doctors, or medicines,” she said. “Doctors don’t want to be posted there. Or they’ll sign up and get paid, but sit in cities, and no one monitors them.”

Chikar is only 137km from Islamabad, but it takes six hours up a switchback road to reach the hospital. Here, the government provides only 10 percent of the community’s medicine needs. CDRS picks up the rest.

Last year, Shea recruited a doctor by doubling his government salary and offering him the only private room in the 20-room hospital, which he rents for US$250 a month. Shea himself sleeps on a mattress in a room he shares with staff members.

“The things you see here are only because of CDRS,” said Dr Rizwan Shabir, 27, who left a comfortable practice in Muzaffarabad, a city of 300,000, to come here. “Frankly, without Todd, there would be no proper medicine, and patients would be dead.”

Still, CDRS is more makeshift than miracle. On a recent morning, Shabir treated 140 patients in five hours. Without blood-testing laboratories, he diagnoses common illnesses like hepatitis and tuberculosis through clinical evaluations.

Outside of Chikar, CDRS supplements 10 other regional government health outposts by paying salaries and purchasing medicines. Overall, it treats about 100,000 patients annually, and 70 percent are women and children.

Shea is an unlikely person to reform Chikar’s decades of medical neglect. At age 12, he went into a deep depression when his mother died of a Valium overdose. By 18, he was addicted to crack cocaine.

In 1992, he moved from his native Maryland to Nashville, Tennessee, to pursue a music career, and spent the next decade playing in bars and restaurants around the country. At one point, he was forced to sell his own blood plasma for US$40 a week to pay the bills.

He moved to New York City in 1998, and had a gig booked at CBGB, the famed music club, on Sept. 12, 2001. As he watched the World Trade Center burn and fall, from his balcony, he promptly emptied his band van and used it over the next week to ferry meals to firefighters at Ground Zero.

He soon became addicted to rescue efforts, and volunteered in Sir Lanka after the tsunami. It was his first time overseas. After Hurricane Katrina, he volunteered with another rescue organization. Then the earthquake hit Pakistan, and he left for a country he knew nothing about.

Once in Chikar, he met a local MBA student, Afzel Makhdoom, who had just dragged his aunt out from under the rubble of his home. As soon as he could scrape together the money, Shea hired him.

“I had never met an American before,” said Makhdoom, now 24. “My first impression was: They just want to kill Muslims; it’s an invasion, and they’ll never go back home. But now we want to keep this American here.”

Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention. If it makes headlines, it is because China wants to invade. Yet, those who find their way here by some twist of fate often fall in love. If you ask them why, some cite numbers showing it is one of the freest and safest countries in the world. Others talk about something harder to name: The quiet order of queues, the shared umbrellas for anyone caught in the rain, the way people stand so elderly riders can sit, the

Taiwan’s fall would be “a disaster for American interests,” US President Donald Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of defense for policy Elbridge Colby said at his Senate confirmation hearing on Tuesday last week, as he warned of the “dramatic deterioration of military balance” in the western Pacific. The Republic of China (Taiwan) is indeed facing a unique and acute threat from the Chinese Communist Party’s rising military adventurism, which is why Taiwan has been bolstering its defenses. As US Senator Tom Cotton rightly pointed out in the same hearing, “[although] Taiwan’s defense spending is still inadequate ... [it] has been trending upwards

After the coup in Burma in 2021, the country’s decades-long armed conflict escalated into a full-scale war. On one side was the Burmese army; large, well-equipped, and funded by China, supported with weapons, including airplanes and helicopters from China and Russia. On the other side were the pro-democracy forces, composed of countless small ethnic resistance armies. The military junta cut off electricity, phone and cell service, and the Internet in most of the country, leaving resistance forces isolated from the outside world and making it difficult for the various armies to coordinate with one another. Despite being severely outnumbered and

Small and medium enterprises make up the backbone of Taiwan’s economy, yet large corporations such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) play a crucial role in shaping its industrial structure, economic development and global standing. The company reported a record net profit of NT$374.68 billion (US$11.41 billion) for the fourth quarter last year, a 57 percent year-on-year increase, with revenue reaching NT$868.46 billion, a 39 percent increase. Taiwan’s GDP last year was about NT$24.62 trillion, according to the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, meaning TSMC’s quarterly revenue alone accounted for about 3.5 percent of Taiwan’s GDP last year, with the company’s