Arctic nations are promising to avoid new “Cold War” scrambles linked to climate change, but military activity is stirring in a polar region where a thaw may allow oil and gas exploration or new shipping routes.

The six nations around the Arctic Ocean are promising to cooperate on challenges such as overseeing possible new fishing grounds or shipping routes in an area that has been too remote, cold and dark to be of interest throughout recorded history.

But global warming is spurring long-irrelevant disputes, such as a Russian-Danish standoff over who owns the seabed under the North Pole, or how far Canada controls the Northwest Passage that the US calls an international waterway.

“It will be a new ocean in a critical strategic area,” said Lee Willett, head of the Marine Studies Programme at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies in London, predicting wide competition in the Arctic area.

“The main way to project influence and safeguard interests there will be use of naval forces,” he said.

Ground forces would have little to defend around remote coastlines backed by hundreds of kilometers of tundra.

Leading climate experts say the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free by 2050 in summer, perhaps even earlier, after ice shrank to a record low in September 2007 amid warming blamed by the UN Climate Panel on human burning of fossil fuels.

Previous forecasts had been that it would be ice-free in summers toward the end of the century.

Among signs of military concern, a Kremlin security document last month said Russia may face wars on its borders in the near future because of control over energy resources — from the Middle East to the Arctic.

Russia, which is reasserting itself after the collapse of the Soviet Union, last year sent a nuclear submarine across the Arctic under the ice to the Pacific. The new class of Russian submarine is called the Borei (Arctic Wind).

Canada runs a military exercise, Nanook, every year to reinforce sovereignty over its northern territories. Russia faces five NATO members — the US, Canada, Norway, Iceland and Denmark via Greenland — in the Arctic.

In February, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper criticized Russia’s “increasingly aggressive” actions after a bomber flew close to Canada before a visit by US President Barack Obama.

And last year Norway’s government decided to buy 48 Lockheed Martin F-35 jets at a cost of 18 billion crowns (US$2.81 billion), rating them better than rival Swedish Saab’s Gripen at tasks such as surveillance of the vast Arctic north.

Much may be at stake. The US Geological Survey estimated last year that the Arctic holds 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil — enough to supply current world demand for three years.

And Arctic shipping routes could be short cuts between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans in summer even though uncertainties over factors such as icebergs, insurance costs or a need for hardened hulls are likely to put off many companies.

Other experts say nations can easily get along in the North.

“The Arctic area would be of interest in 50 or 100 years — not now,” said Lars Kullerud, president of the University of the Arctic. “It’s hype to talk of a Cold War.”

He said an area in dispute between Russia and Denmark at the North Pole was no bigger than a “gray zone” in the Barents Sea over which Russia and Norway have been at odds for decades and where seismic surveys indicate gas deposits in shallow waters.

“The talk of a new Cold War is exaggerated,” said Jakub Godzimirski of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

“We have seen a lot of shipping traffic going all over the world without tensions,” he said.

Governments also insist a thaw does not herald tensions.

“We will seek cooperative strategies,” US Deputy Secretary of State Jim Steinberg said during a meeting of Arctic Council foreign ministers in Tromsoe, Norway.

“We are not planning any increase in our armed forces in the Arctic,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said at the talks in late April, stressing cooperation.

“Everyone can make easy predictions that when there are resources and there is a need for resources there will be conflict and scramble,” Norwegian Foreign Minister Jonas Stoere said. “It need not be that way.”

Agreeing with them that Cold War talk is exaggerated, Niklas Granholm of the Swedish Defence Research Agency nonetheless said: “The indications we have is that there will be an increased militarization of the Arctic.”

That would bring security spinoffs. Many may be humdrum — ensuring safety of shipping or deployment of gear in case of oil spills such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez accident in Alaska.

Wider possibilities include a possible race between Russia and the US for quieter nuclear submarines.

Submarines, which can launch long-range nuclear missiles, have long had a hideout under the fringe of the Arctic ice pack where constant waves and grinding of ice masks engine noise.

“It might lead to a new generation of ultra-silent submarines or other, new technologies,” Granholm said.

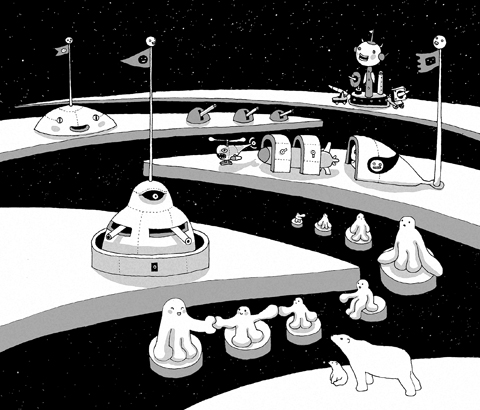

Greater access to Arctic resources and shipping is one of few positive spinoffs as climate change undermines the hunting cultures of indigenous peoples and threatens wildlife from caribou to polar bears.

The Northwest Passage past Canada, for instance, cuts the distance between Europe and the Far East to 7,900 nautical miles (14,630km) from 12,600 nautical miles via the Panama Canal. Similar savings can be made on a route north of Russia.

A UN deadline for coastal states to submit claims to offshore continental shelves passed on May 13, and in 2007 Russia planted a flag on the seabed in 4,261m of water under the pole to back its claim.

Russia’s flag-planting stunt might also herald new technologies — the world record for drilling in deep water is 3,051m, held by Transocean Inc, the world’s largest offshore drilling contractor.

Claims by Norway and Iceland do not extend so far north and Denmark, Canada and the US were not bound by the deadline.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while

I have heard people equate the government’s stance on resisting forced unification with China or the conditional reinstatement of the military court system with the rise of the Nazis before World War II. The comparison is absurd. There is no meaningful parallel between the government and Nazi Germany, nor does such a mindset exist within the general public in Taiwan. It is important to remember that the German public bore some responsibility for the horrors of the Holocaust. Post-World War II Germany’s transitional justice efforts were rooted in a national reckoning and introspection. Many Jews were sent to concentration camps not