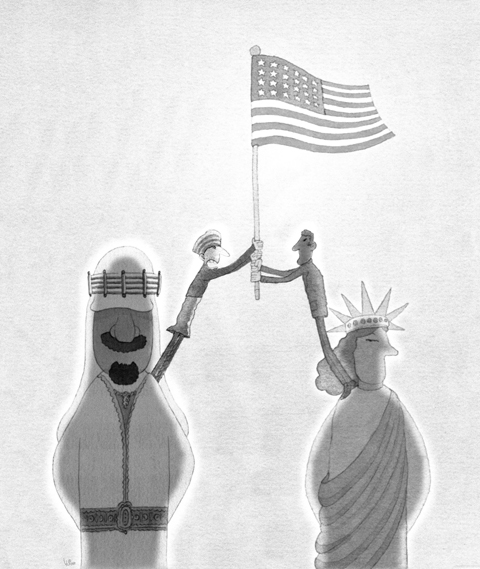

US President Barack Obama has extended an open hand of friendship in his landmark Cairo speech to the Muslim world — seeking to engage Muslims with a commitment of mutual respect. No one can doubt his sincerity. From his first days in office, he has emphasized the importance of embarking on a new chapter in relations between the US and the world’s Muslims.

But this aspiration will remain elusive without acknowledging the sad fact that most Americans remain woefully ignorant about the basic facts of Islam, and about the broad geographic and cultural diversity of Muslim cultures.

A majority of public opinion polls taken in the last four years show that the views of Americans about Islam continue to be a casualty of the Sept. 11 attacks.

Washington Post/ABC News polls from 2006, for example, found that nearly half of Americans regard Islam “unfavorably,” while one in four admits to prejudicial feelings against Muslims.

US views of the Muslim world are so colored by the conflict in the Middle East and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan that US citizens have no collective appreciation of the fact that most Muslims live in Asia. Or that the four countries with the largest Muslim populations — Indonesia, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh — are all cultures with millennia-old histories of coexisting with other religions and cultures.

A 2005 report by the US State Department’s Advisory Committee on Cultural Diplomacy called for a new vision of cultural diplomacy that “can enhance US national security in subtle, wide-ranging and sustainable ways.” Last year, a bipartisan group of US leaders — the US-Muslim Engagement Project — convened by Search for Common Ground and the Consensus Building Institute, issued a report calling for a new direction for US relations with the Muslim world. A primary goal of this effort would be “to improve of mutual respect and understanding between Americans and Muslims around the world.”

It is time for US citizens to commit themselves to working alongside the Obama administration to turn a new leaf in relations with the Muslim world. The first step is to make a concerted effort to become better educated about the multifaceted societies that comprise the 1 billion-strong Muslim population throughout the world.

The power of culture resides in its ability to transform perceptions. This week, New Yorkers are experiencing the rich diversity of Muslim cultures through a city-wide initiative, entitled “Muslim Voices: Arts and Ideas.” More than 300 artists, writers, performers and academics from more than 25 countries, including the US, are gathering for this unprecedented festival and conference.

Presentations include a dizzying variety of artistic forms from the Muslim world, ranging from the traditional (calligraphy, Sufi devotional voices) to the contemporary (video installations, avant-garde Indonesian theater and Arabic hip-hop). A companion policy conference has attracted scholars and artists from around the world exploring the relationship between cultural practice and public policy and suggesting new directions for cultural diplomacy.

A critical goal of this project is to help break stereotypes and create a more nuanced understanding of Muslim societies.

Despite our enthusiasm for the possibilities of what this initiative can do to broaden understanding, a performance, a film, or an art exhibition cannot find solutions to all of the problems that divide Americans and the Muslim world. The current distance is rooted as much in ignorance as in hard political issues, many of which go beyond what arts and culture can realistically address.

However, cultural diplomacy and initiatives such as “Muslim Voices” can open the door to the reality of the Muslim world as a rich space for world-class artistic production. That, in turn, can encourage an interest in addressing the harder political issues with respect and a sense of equity.

For too long, the differences between the US and the Muslim world have been framed not in terms of diversity, but as the foundations of a permanent global conflict. But when people participate in an aesthetic experience that both addresses and transcends a particular culture, perceptions are bound to change.

The US has reached a pivotal moment in its national and global history, with new hopes for intercultural exchange, dialogue and mutual understanding. Obama and US Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton say that theirs will be an age of “smart power” that will effectively use all tools of diplomacy at their disposal, including cultural diplomacy.

The US must focus once again on the arts as a meaningful way to promote stronger cultural engagement and, ultimately, to find new channels of communication with the Muslim world.

Doing so will show that relations need not be defined only through political conflict. Rather, there is now an opportunity to define connections between the US and the Muslim world by sharing the richness and complexity of Muslim artistic expressions — as a vital step in finding grounds for mutual respect.

Vishakha Desai is president of the Asia Society; Karen Brooks Hopkins is president of the Brooklyn Academy of Music; and Mustapha Tlili is founder and director of the Center for Dialogues: Islamic World-US-The West at New York University.

COPYRIGHT: PROJECT SYNDICATE

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

US President Trump weighed into the state of America’s semiconductor manufacturing when he declared, “They [Taiwan] stole it from us. They took it from us, and I don’t blame them. I give them credit.” At a prior White House event President Trump hosted TSMC chairman C.C. Wei (魏哲家), head of the world’s largest and most advanced chip manufacturer, to announce a commitment to invest US$100 billion in America. The president then shifted his previously critical rhetoric on Taiwan and put off tariffs on its chips. Now we learn that the Trump Administration is conducting a “trade investigation” on semiconductors which

By now, most of Taiwan has heard Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an’s (蔣萬安) threats to initiate a vote of no confidence against the Cabinet. His rationale is that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)-led government’s investigation into alleged signature forgery in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) recall campaign constitutes “political persecution.” I sincerely hope he goes through with it. The opposition currently holds a majority in the Legislative Yuan, so the initiation of a no-confidence motion and its passage should be entirely within reach. If Chiang truly believes that the government is overreaching, abusing its power and targeting political opponents — then