When Tokyo prosecutors arrested an aide to a prominent opposition political leader in March, they touched off a damaging scandal just as the entrenched Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) seemed to face defeat in coming elections.

Many Japanese cried foul, but you would not know that from the coverage by Japan’s big newspapers and TV networks.

Instead, they mostly reported at face value a stream of anonymous allegations, some of them thinly veiled leaks from within the investigation, of illegal campaign donations from a construction company to the opposition leader, Ichiro Ozawa.

This month, after weeks of such negative publicity, Ozawa resigned as head of the opposition Democratic Party.

The resignation, too, provoked a rare outpouring of criticism aimed at the powerful prosecutors by Japanese across the political spectrum, and even from some former prosecutors, who seldom criticize their own in public. The complaints range from accusations of political meddling to concerns that the prosecutors may have simply been insensitive to the arrest’s timing.

But just as alarming, say academic and former prosecutors, has been the failure of the news media to press the prosecutors for answers, particularly at a crucial moment in Japan’s democracy, when the nation may be on the verge of replacing a half-century of LDP rule with more competitive two-party politics.

“The mass media are failing to tell the people what is at stake,” said Terumasa Nakanishi, a conservative academic who teaches international politics at Kyoto University. “Japan could be about to lose its best chance to change governments and break its political paralysis, and the people don’t even know it.”

The arrest of the aide seemed to confirm fears among voters that Ozawa, a veteran political boss, was no cleaner than the Liberal Democrats he was seeking to replace. It also seemed to at least temporarily derail the opposition Democrats ahead of the elections, which must be called by early September. The party’s lead in opinion polls was eroded, though its ratings rebounded slightly after the selection this month of a new leader, Yukio Hatoyama, a Stanford-educated engineer.

Japanese journalists acknowledge that their coverage so far has been harsh on Ozawa and generally positive toward the investigation, though newspapers have run opinion pieces criticizing the prosecutors. But they bridle at the suggestion that they are just following the prosecutors’ lead, or just repeating information leaked to them.

“The Asahi Shimbun has never run an article based solely on a leak from prosecutors,” the newspaper, one of Japan’s biggest dailies, said in a written reply to questions from the New York Times.

Still, journalists admit that their coverage could raise questions about the Japanese news media’s independence, and not for the first time. Big news organizations here have long been accused of being too cozy with centers of power.

Indeed, academics say coverage of the Ozawa affair echoes the positive coverage given to earlier arrests of others who dared to challenge the establishment, like the iconoclastic Internet entrepreneur Takafumi Horie.

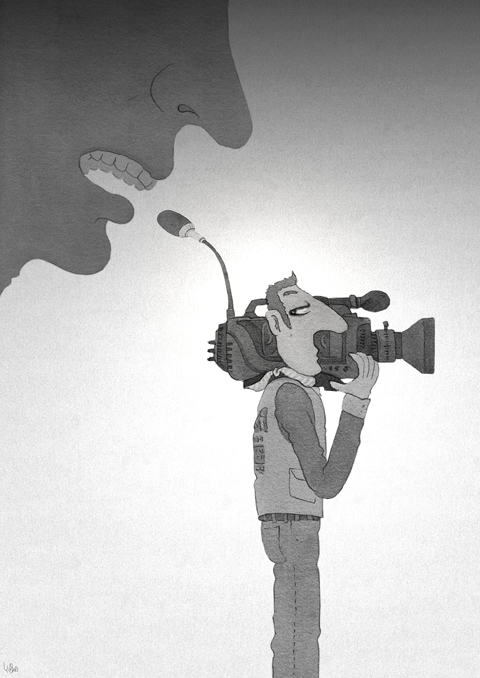

“The news media should be watchdogs on authority,” said Yasuhiko Tajima, a journalism professor at Sophia University in Tokyo, “but they act more like authority’s guard dogs.”

While news media in the US and elsewhere face similar criticisms of being too close to government, the problem is more entrenched here. Cozy ties with government agencies are institutionalized in Japan’s so-called press clubs, cartel-like arrangements that give exclusive access to members, usually large domestic news outlets.

Critics have long said this system leads to bland reporting that adheres to the official line. Journalists say they maintain their independence despite the press clubs. But they also say government officials sometimes try to force them to toe the line with threats of losing access to information.

Last month, the Tokyo Shimbun, a smaller daily known for coverage that is often feistier than that in Japan’s large national newspapers, was barred from talking with Tokyo prosecutors for three weeks after printing an investigative story about a governing-party lawmaker who had received donations from the same company linked to Ozawa.

The newspaper said it was punished simply for reporting something the prosecutors did not want made public.

“Crossing the prosecutors is one of the last media taboos,” said Haruyoshi Seguchi, the paper’s chief reporter in the Tokyo prosecutors’ press club.

The news media’s failure to act as a check has allowed prosecutors to act freely without explaining themselves to the public, said Nobuto Hosaka, a member of parliament for the opposition Social Democratic Party, who has written extensively about the investigation on his blog.

He said he believed Ozawa was singled out because of the Democratic Party’s campaign pledges to curtail Japan’s powerful bureaucrats, including the prosecutors. (The Tokyo prosecutors office turned down an interview request for this story because the Times is not in its press club.)

Japanese journalists defended their focus on Ozawa’s alleged misdeeds, arguing that the public needed to know about a man who at the time was likely to become the next prime minister. They also say they have written more about Ozawa because of a pack-like charge among reporters to get scoops on those who are the focus of an investigation.

“There’s a competitive rush to write as much as we can about a scandal,” said Takashi Ichida, who covers the Tokyo prosecutors office for the Asahi Shimbun.

But that does not explain why in this case so few Japanese reporters delved deeply into allegations that the company also sent money to LDP lawmakers.

The answer, as most Japanese reporters will acknowledge, is that following the prosecutors’ lead was easier than risking their wrath by doing original reporting.

The news media can seem so unrelentingly supportive in their reporting on investigations like that into Ozawa that even some former prosecutors, who once benefited from such favorable coverage, have begun criticizing them.

“It felt great when I was a prosecutor,” said Norio Munakata, a retired, 36-year veteran Tokyo prosecutor. “But now as a private citizen, I have to say that I feel cheated.”

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

The military is conducting its annual Han Kuang exercises in phases. The minister of national defense recently said that this year’s scenarios would simulate defending the nation against possible actions the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) might take in an invasion of Taiwan, making the threat of a speculated Chinese invasion in 2027 a heated agenda item again. That year, also referred to as the “Davidson window,” is named after then-US Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson, who in 2021 warned that Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) had instructed the PLA to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. Xi in 2017

If you had a vision of the future where China did not dominate the global car industry, you can kiss those dreams goodbye. That is because US President Donald Trump’s promised 25 percent tariff on auto imports takes an ax to the only bits of the emerging electric vehicle (EV) supply chain that are not already dominated by Beijing. The biggest losers when the levies take effect this week would be Japan and South Korea. They account for one-third of the cars imported into the US, and as much as two-thirds of those imported from outside North America. (Mexico and Canada, while