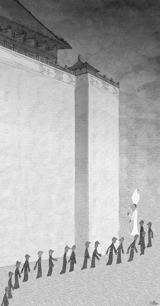

Israel’s Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem, is housed within an angular concrete corridor that leads visitors through appalling stories of persecution, suffering and death and out eventually to a calming view over the Jerusalem forests.

Halfway down the corridor in a room on the left are two black and white photographs of the wartime pope, Pius XII, with a few lines of text in English and Hebrew. It is one of hundreds of displays in the museum and easily overlooked, but it runs to the heart of Israel’s often troubled relationship with the Vatican.

Pope Benedict XVI is making an official visit to the Holy Land this week and attended Yad Vashem yesterday to lay a wreath, but he did not visit the museum or see the caption. The wording set off a diplomatic spat two years ago when the papal envoy to Jerusalem threatened to skip Israel’s Holocaust day service and it remains contentious, symbolic of the troubled history between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people.

For some, Pius XII was little more than “Hitler’s pope” and the caption at Yad Vashem is accusatory. It claims Pius “shelved” a letter against racism and anti-Semitism prepared by his predecessor and says that when the Vatican received news of the murder of Jews “the pope did not protest either verbally or in writing.”

In December 1942 he “abstained” from signing an allied declaration against the extermination of Jews, and when Jews were deported from Rome to Auschwitz “he did not intervene.”

“His silence and the absence of guidelines obliged churchmen throughout Europe to decide on their own how to react,” it says.

Israeli academics, including researchers at Yad Vashem itself, have pressed the Vatican to open its wartime archives and shed light on documents that might explain in more detail how the Catholic Church acted. Workshops and discussions on the Holocaust have been held between Yad Vashem staff and Catholic clergy.

Vatican officials have tried to smooth over the differences, although Pius remains on track for canonization. Monsignor Antonio Franco, the papal envoy who threatened to stay away from the Holocaust service two years ago, said this week that the Vatican was making a “huge effort” to accelerate the opening of the archives. Perhaps within four or five years they might be revealed, he said.

“It really demands a lot of work, a lot of investigation and things must be done in a very professional way,” he said.

Pope Benedict was not coming to Israel to quarrel, Franco said, but at 82 he was an elderly man with a busy schedule and a visit to the museum had “never been on the agenda.”

This despite the fact that in 2000 his more charismatic predecessor, John Paul II, spent several hours at Yad Vashem listening to Holocaust survivors.

Vatican officials have also been at pains to describe the papal tour as a pilgrimage, not a political visit. But in reality it holds much more significance. It will be only the third visit of a pope to the Holy Land and comes at a time when hope of a genuine peace between Israel and the Palestinians is ever more illusory.

More and more Christians are leaving the area, particularly the Palestinian territories, for several reasons, among them perceived persecution by Muslims and the suffocating and deadly effect of Israel’s four-decade occupation.

Only in 1993 did the Vatican sign an accord recognizing the state of Israel, but the “fundamental agreement” between the two sides, with its 15 articles about property rights and hugely valuable tax exemptions, has still not been implemented. Negotiations continue.

There are other issues of dispute, some theological, others practical. Many Israelis were angered by the pope’s decision in January to revoke the excommunication of the British bishop Richard Williamson, who denied the existence of the Nazi gas chambers. Senior Jewish leaders said that decision threatened the reconciliation between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people. In February, an Israeli TV show was forced to apologize after airing a sketch that ridiculed Jesus and Mary.

Some opinion polls have suggested these differences run deep. A poll of Jewish Israelis by the Jerusalem Centre for Jewish-Christian Relations last year found that 41 percent regarded Christianity as an idolatrous religion, and 46 percent did not believe Jerusalem was a central city for the Christian world. Some 40 percent believed the Catholic Church had a very or largely negative attitude towards Judaism and Jews.

Hardliners have played on this and on Benedict’s own background growing up in wartime Germany. Michael Ben Ari, a far-right Israeli member of parliament, said on Tuesday that the pope’s visit would be an insult to the memory of Holocaust victims.

“A state welcome for the pope would be turning our backs on the millions of Jews who were killed in the shadow of the Christian religion of grace and mercy,” he told a session of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. “This pope was a member of the Hitler Youth.”

Among Palestinians, political expectations are high. They hope Benedict will speak out in support of Palestinian independence. After he says mass in Bethlehem tomorrow he will visit Aida, a Palestinian refugee camp, where a stone stage has been built for him next to Israel’s vast concrete West Bank barrier. Fouad Twal, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, said the camp itself symbolized the “right of return” for Palestinian refugees who were forced out or fled from what is now Israel in the 1948 war.

However, it is far from clear whether Benedict will speak out on these political issues, and it now seems doubtful that he will even reach the stage in Aida camp.

Elsewhere there are more careful voices. Father William Shomali, rector of the Latin seminary in Beit Jala, next to Bethlehem, said there was little point hoping that the pope’s visit might alter the reality of the conflict.

“After hundreds of meetings between committees and subcommittees we are still negotiating how and with whom to negotiate,” he said. “I don’t want it to be a political visit or it will continue the frustration.”

Instead, he hoped the pope would emphasize prayer, acknowledgement of the suffering of others, reconciliation and religious dialogue.

“If everyone recognizes his own guilt, reconciliation becomes easier,” he said.

As for Pius XII and his wartime conduct, although it is true the Vatican has been slow to study the issue in detail, it also appears that Yad Vashem’s verdict is not the last word.

Some historians, among them Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s biographer, have come out in support of Pius as in fact an unsung hero of the war. He points out that the pope’s 1942 Christmas message infuriated the Nazis because it defended the Jews, and notes that the pope organized rescues of Jews in Hungary and intervened to stop deportations in Slovakia. In 1943, Pius tried to disrupt implementation of the Final Solution throughout occupied Italy.

Nearly 5,000 Jews, Gilbert says, were sheltered in Catholic institutions across Rome with the result that a larger proportion of Jews were saved there than in any other city under German occupation.

By Rory McCarthy

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its